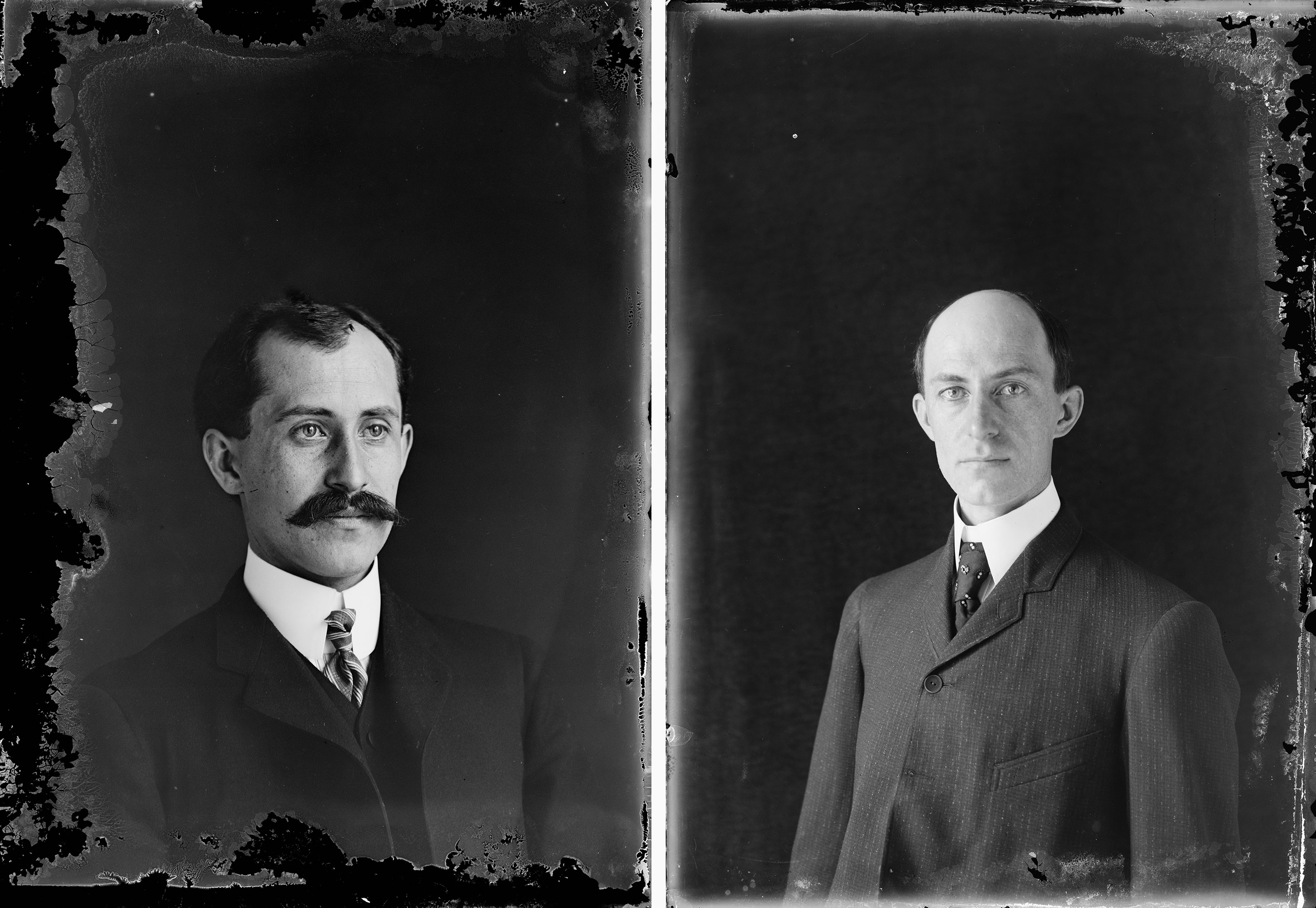

Photographic plates of 1905 brought to us portraits of Orville Wright (34 years old) and Wilbur Wright (38 years old).

On December 17, 1903, the brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright made their first successful flight on a vehicle heavier than air. They were able to fly into their car, the Flyer, right into the history books. But also, in the next decade, their car carried them through courtrooms throughout Europe and North America.

In the courts, the Wright brothers waged a long, unsightly, and for the most part unsuccessful battle against other aviation pioneers over the issue of belonging to the principles of aeronautics that make flights possible. The Wright brothers cited the 1906 patent on their car and claimed that these principles belong to them, accusing competitors of stealing intellectual property. Fighting in court, Wright's rivals argued that the theory behind the machines is the public domain of mankind, and argued that Wright’s patent refers only to the design of their airplane.

During this battle, Wright proved to be not only the pioneers of aviation. They also showed themselves as pioneers of what is sometimes referred to as patent trolling: the controversial current practice of litigating with competitors over infringements beyond the scope of the patent. Thus, their legacy is not only genius and innovation, but also litigation and an obstacle to progress. Promoting aeronautics neither shakily nor swiftly at the beginning of the 20th century, Orville and Wilbur Wright spent their talents and energy - as well as the talents and energy of their most gifted competitors - on legal battles that took place from 1909 to 1917. As a result, American aviation suffered immeasurably, and Wright set dangerous precedents for future generations of future patent trolls.

The Wright Brothers patent requirements worked in much the same way as today's patent trolls. Consider the often cited example of patent troubles of the past decade: the case of Personal Audio . The company owned a 2001 patent for “an audio and message distribution system in which the central system organizes and transmits program segments to subscribers in different places,” which it used in connection with the alleged release of an MP3 player (which was never released). After her patent infringement lawsuits were rejected in April 2015, the company used this patent to prove that she had invented the idea of podcasts and that podcasters were thus stealing their intellectual property. The lawsuits have been separated for a hundred years, but the overall requirements of Personal Audio and the Wright brothers are essentially identical.

To understand Wright’s claims, you must first examine the contents of their patent. The patent they received three years after the first flight described a “flying machine”, with emphasis on the brothers' most revolutionary contribution to aeronautics research: their innovative in-flight control mechanism.

According to Wright’s scheme - and in almost all later planes - control was carried out using what the brothers called the "transverse edges" of the wings of the aircraft. In practice, this meant the need to move the rear outer tips of the wings in different directions, which Wright achieved with the help of cables that bend the Flyer's wings made of wood and fabric. For example, try twisting the ends of a box of spaghetti in different directions.

Curvature of the wings was a key innovation that made manned flight with a motor a meaningful reality. And although earlier models of airplanes could come off the ground, all of them were essentially unstable and incredibly dangerous. Orville and Wilbur were justifiably proud of their idea and deserved any intellectual property protection the law could provide.

However, Wright wanted to patent not only his own mechanism for curving the wings, but also all future devices that could move the “transverse edges” of the wings of an airplane — that is, file a legal application for the principles of aeronautics they discovered. If the patent were interpreted as they wanted, it would provide them with a monopoly in the aviation market for many years.

Fortunately for the subsequent history of aviation, many of Wright's early rivals agreed to risk participating in a legal battle. One of those competitors was Glenn Curtiss , a motorcycle manufacturer who became an airplane designer, and turned into one of Wright's most fierce rivals. Equipping his plane with movable flaps called ailerons, instead of a mechanism for curving the wings, Curtiss hoped to avoid infringement of Wright's patent. But since managing his plane worked on the same principle, Wright felt that it was worth the trial.

Curtiss, however, was not alone in his legal trouble. Between 1909, when Wright first sued Curtiss, and 1917, when Wright's patent was suspended, the brothers filed a lawsuit against one of the true heroes of early aviation.

The financial results of the lawsuits were mixed. A German judge dismissed Wright’s lawsuit. The French court sided with them. In the US, judges twice refused Curtiss - although, as in France, legal disputes did not allow the brothers to collect any significant royalties until the patent war was resolved. Meanwhile, the ongoing threat of receiving letters with harsh language from Wright's lawyers convinced the more timid competitors to swallow their pride and pay the brothers significant amounts for the opportunity to exhibit their aircraft.

However, if the financial results of the patent war were mixed, its impact on American aviation was certainly negative. Even before Wilbur died in 1912, at the height of the lawsuit, Wright neglected research and development. By 1915, when Orville had sold the company he had founded with his brother, their plane was ridiculed as dangerous and outdated. Causing envy once, the Wright plane became a laughing stock. Meanwhile, while other US developers continued to develop impressive innovations during the patent wars, the US aviation industry as a whole was inhibited by litigation. By the time the US participated in World War I in 1917, the state of domestic aviation was so dull that the US government could not find a single aircraft suitable for military service. Thus, the country that invented flying vehicles with a motor plowed the war-torn skies of Europe in foreign aircraft.

Frustrated by this state of affairs, politician Franklin Delano Roosevelt , who was actively tearing upstairs, then serving as an assistant to the Minister of the Navy, decided to act. By putting pressure on key players in the American aeronautics industry, Roosevelt persuaded intellectual property holders to form a patent pool that would allow aircraft manufacturers to use each other's technology for a modest fee. Thus, Roosevelt, in fact, led the patent war to the long-required final.

This is not to say that Wright lost the patent war. Orville and Wilbur received a lot of money from frightened competitors, despite the lack of a clear court decision in their favor. But in the long run, numerous circumstances - among which the most important was historical development - turned against Wright, ensuring that the principles of aeronautics discovered by them belong to everyone.

Today we must remember not only the first historical flight of the Wright, but also the years of useless and unpleasant legal conflicts in which they embroiled the industry they founded.