How was the classic? "I looked around me - my soul became wounded by the sufferings of mankind."

Exactly. Don’t even go to the social networks, “boulder crunches”, “commies” and “liberals” are again fighting to the death on the Internet, screams are multiplying, fans are overheating, and no one wants to give in. All require the immediate execution of their own mrias, and no one wants to live in reality.

Want to tell the real life story of one real person? As often happens with me - incomplete, stripped down, but therefore no less significant.

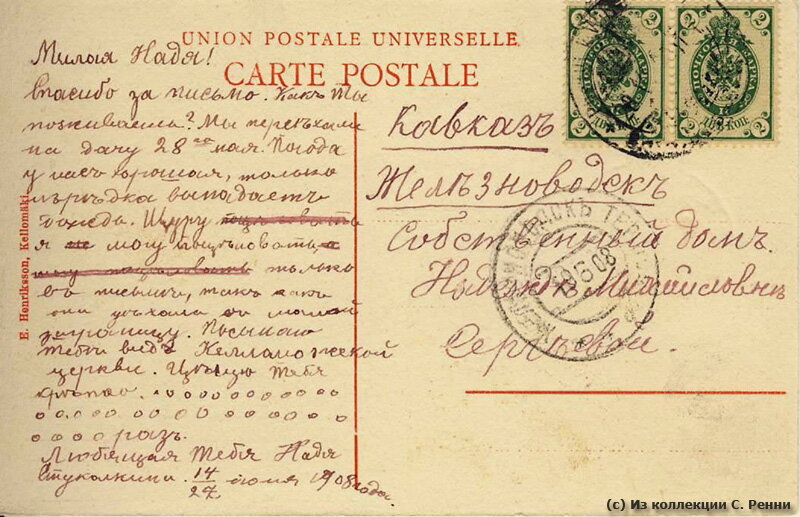

For me, this story began with the site "Letters from the Past", where collectors of postcards gather. There was revealed the correspondence of two girls, two gymnasium students, two Nagy.

There is nothing special - the usual correspondence between two Petersburg friends, one of whom left for the summer with her dad in the then-not-resort Zheleznovodsk, and the second misses her own - which is rare - cottage in Kellomyaki.

June 1908, six years before the great war, nine years before the great revolution. Nadia Stukolkina sends a postcard with a view of Kellomyaki to Nadia Sergeeva:

“Dear Nadia! Thank you for your letter. How are you? We moved to the cottage on May 28. We have good weather, only occasionally it rains. I can kiss Shura only in a letter, since they left my mother abroad. I am sending you a view of the Kellomyak church. I kiss you hard 1000000000000000000000000000000 times.

Loving you, Nadia Stukolkina.

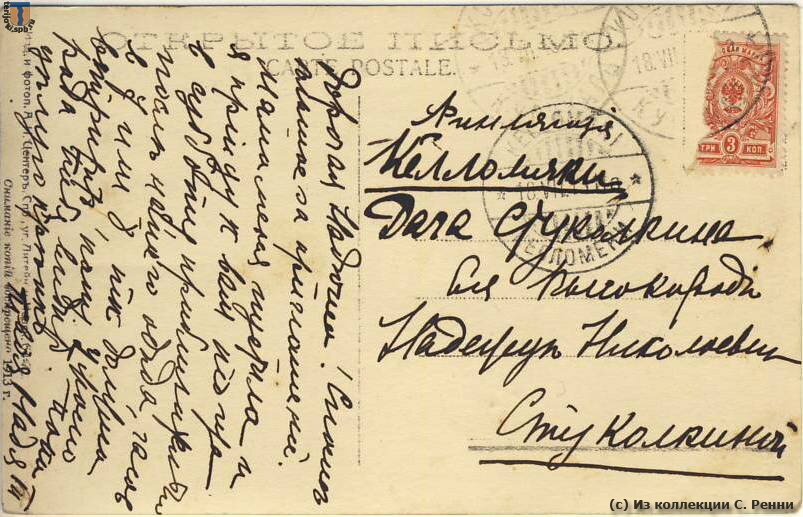

The second postcard, continuing the “country correspondence”, was sent four years later, in August 1912.

The card was sent from Kuokkala to the Terioka station, Vammelsu, Metsekuli, Sycheva cottage. The recipient is the same Nadia Sergeeva.

Girls have grown up, they are no longer children, which is noticeable at least in handwriting, and their hobbies are already almost adults. As they would say today, they are interested in “the latest gadgets” - they photograph on photographic plates:

Dear Nadyusha! How is your health. Have you recovered? I don’t already know what to think, because I haven’t received anything from you. Recently we had competitions. I hung out there all day. Are you showing my records? I am eager to see my wonderful image. Bye see you. I kiss you deeply and sincerely.

The third postcard was written the following summer, in the pre-war year of 1913, and in it already Nadia Sergeeva writes to her friend Nadia Stukolkina - there, in Kellomyaki from Kuokkala.

Dear Nadia. Thank you very much for the invitation. Mom let me in, and I will come to you on Saturday, approximately after our lunch, at 7 or 8, as I should meet dad. Awfully glad to see you. Till. Kisses tightly.

Your Nadia.

That, in fact, is all the correspondence. Agree, there is nothing special about it. Is that the image of that, long gone, era.

The inquisitive and curious inhabitants of the site “Letters from the Past” restored the identities of both friends.

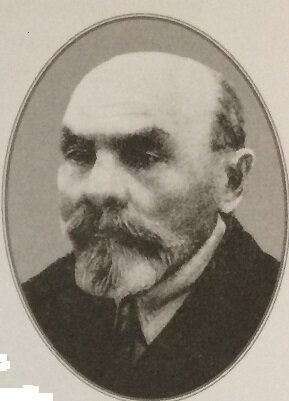

Nadia Stukolkina is the granddaughter of the famous Russian ballet dancer Timofei Alekseevich Stukolkin.

Her father, Nikolai Timofeevich Stukolkin, was a famous architect, a graduate of the Imperial Academy of Arts. In 1891 he became an architect of the Palace Administration, and until 1917 he was in this position, rose to the rank of “State Counselor”.

Itself built a little, rebuilt more, but among its reconstructions there are very interesting things, such as the chapel of St. Prince Alexander Nevsky in the fence of the Summer Garden, which was erected on the site of the attempt on the life of Alexander II by Karakozov. Now it no longer exists, but it looked like this:

In St. Petersburg, the Stukolkins lived on Fontanka Embankment 2, in residential buildings of the court department, which the architect himself rebuilt in 1907-1909.

The Stukolkin family after the revolution remained in Russia, in the Soviet Union Nikolai Timofeevich worked as an architect and engineer.

He died of starvation in the most terrible first siege of winter at 78 years of life.

I did not find any information about the fate of Nadi Stukolkina.

It is only clear that she too long passed away - her friends were clearly born either at the turn of the century, or, more likely, at the very end of the 19th century.

None of them are already there, but the Stukolkin’s dacha is still alive in Kellomyaki, where little Nadia wrote to her friend in the Caucasus, and where she was planning to come to the “pajama party” Nadia Sergeeva in 1913. True, the village of Kellomyaki is now called Komarovo. Yes, yes, the same where everyone goes exclusively for a week.

And the Stukolin family in Komarovo - here it is:

Or even, from a different angle:

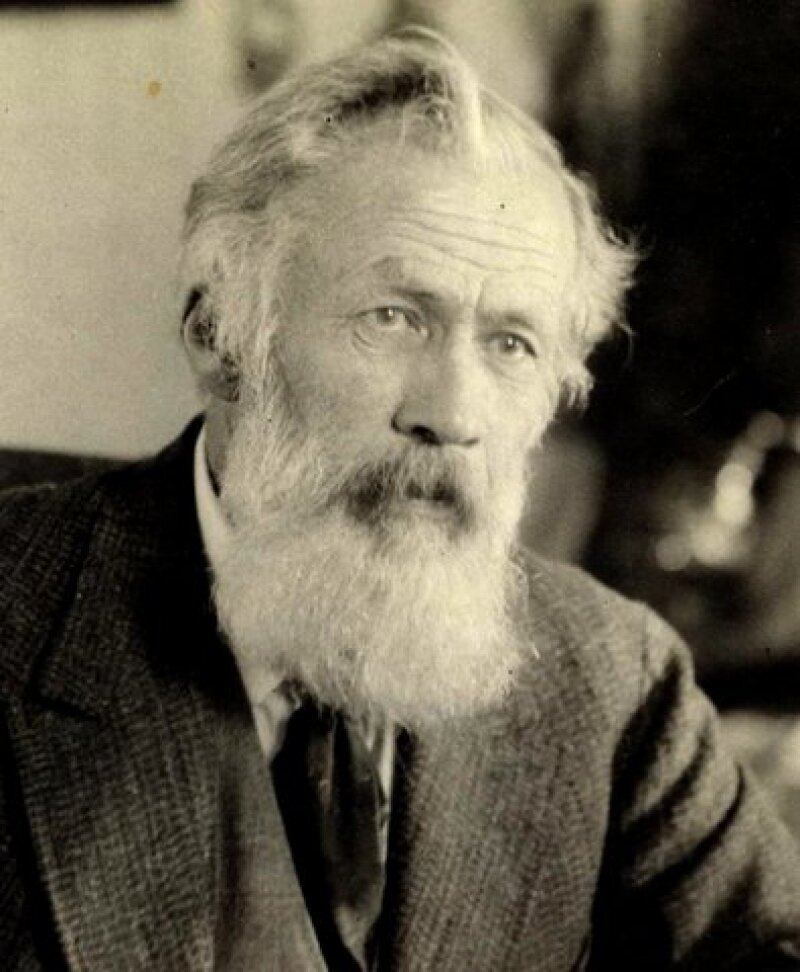

As for Nadia Sergeeva, she was the daughter of mining engineer Mikhail Vasilievich Sergeev, a famous Russian and Soviet hydrogeologist, one of the creators of this scientific field in Russia. Mikhail Vasilievich was the pioneer of the Pyatigorsk narzan (1890), the head of the Technical Department of the Mining Department with a salary of 1,500 rubles, a full member of the Russian Geographical Society and a full state adviser, holder of many orders.

By the way, one of the four people who determined the fate of the city of Sochi, where people who know the congregation live. So many experts were part of the Commission for the Study of the Black Sea Coast of the Caucasus. It was Sergeyev’s comrades who, at the end of the work of the Commission, submitted detailed reports on the resort prospects of Sochi and the surrounding area to the Cabinet of Ministers.

In general, Sergeyev did quite a lot for Sochi, he came there to work with his family every summer and, among other things, was even elected a friend (deputy) of the chairman of the Sochi branch of the Caucasian Mountain Club - the first domestic mountain tourists and climbers.

Participants in the Sochi branch of the Caucasian Mountain Club conduct an excursion to Lake Kardyvach. Krasnaya Polyana. At the dacha of Konstantinov. 1915 year.

Each year, the head of the Sergeyev family went to explore new mineral springs (Polyustrovsky (1894), Starorussky (1899, capture in 1905), Caucasian (1903), Lipetsk (1908), Sergievsky (1913), etc.), so the family later moved from Sochi to Zheleznovodsk, having bought a house for summer living there ...

In general, childhood with Nadia Sergeeva was not boring.

After the revolution, the Sergeevs also remained in their homeland. Father since 1918 served in the Supreme Economic Council, was the head of the mineral water section, chairman of the Glavsol trust. He devoted a lot of time to teaching at the Moscow Mining Academy - my Red Hogwarts.

He was the first dean of the faculty of mining (in 1921 he handed over the position to V. A. Obruchev, who is an academician, the hero of Socialist Labor and the author of “Plutonium” and “Sannikov Earth”), professor, head of the department of hydrogeology.

In general, even the most difficult years after the revolution, the Sergeevs survived normally, except that they had to move from Petersburg to Moscow. It is good to be a unique specialist in some useful business - everyone needs them and will not remain without work under any conditions.

Mikhail Vasilievich Sergeev lived a very long and very fruitful life. He died before the war, in 1939, but back in May 1938, Academician V.I. Vernadsky wrote in his diary: “There was Mikh [ail] Vasilievich Sergeyev, an old (over 80) mining engineer, water specialist. They talked with him about holding a commission on a note for the Presidium (USSR Academy of Sciences) on the protection of waters.

And the girl Nadia ... The girl Nadia grew up.

Twenties were hungry, so Nadia went to work. Gymnasium education and daddy’s influence was enough for a young girl to be taken to a lower position in the library of the Moscow Mining Academy in 1922. In the famous reference book “All Moscow” for 1929

we can even see the name of our heroine:

I would really like to know with what eyes the girl Nadia looked at my heroes, her peers, at these illiterate, still smelling of blood, “cubs of revolution”, when she gave them books in the library? On the same Fadeev and Zavenyagin, who had never completely washed away the soot of the Civil War ... With admiration? With fear? With envy? Cautiously? With squeamishness? With hate?

You won’t ask any more - everyone is gone.

I was always interested - how are these recent schoolgirls from good families with dachas in Kuokkale and fathers - state advisers who served the hereditary nobility - how did they perceive the whole storm that raged in Russia after the revolution?

It is clear that the same Nadia was going to live a completely different life, but she did not prepare for what happened in 1917. And the position of the librarian's assistant in the MGA, procured by dad, then, in the twenties, was probably considered as a temporary measure, as an opportunity to sit out difficult times ...

But it turned out that the building on Kaluga is for life.

And now there is a big gap in my story, and we will have to jump from the 20s right into the 50s.

Postwar USSR. More Stalinist times, but already at the end. Something already rushes in the air - the leader is old, the era is ending, everyone understands this, but no one knows what will happen next. In the meantime, everything is on the thumb.

In general, 1951.

In the institute's long run of the Moscow Institute of Steel - one of the fragments of the Moscow Mining Academy, in the March issue of the newspaper with the obvious name "Steel" - the festive strip "Women of the country of socialism".

The note is called "One of the best."

And in it is finally a photograph of former gymnasium student Nadia Sergeeva.

And the note - here it is:

If you ask any of the Institute’s employees who they consider to be the best employees in our team, there is no doubt that Nadezhda Mikhailovna Sergeeva will be named among the first.

N. M. Sergeeva has been working at the institute since the day it was founded and is doing an excellent job managing the library. She is a proven social activist in the best sense of the word, a permanent member of the party bureau of the institute’s apparatus, and now she is the secretary of the party bureau and the head of the political circle of the apparatus’s workers. Nadezhda Mikhailovna is an excellent organizer, has a broad outlook, knows how to attract others to social work, acting primarily by personal example. Nadezhda Mikhailovna does not count with time if the matter requires it. And therefore, N. M. Sergeyev is loved and respected in our country, people come to her to consult not only on issues of public work, but also on a wide variety of everyday issues.

Always friendly and sympathetic, N.M. Sergeeva is able to help everyone in one way or another in his work, guided by the principle that in the Soviet collective the needs and concerns of each individual comrade are at the same time the needs and concerns of the entire collective as a whole.

For his work, N. M. Sergeeva has a number of government awards, has been repeatedly noted by the management and public organizations of our institute among its best employees. Her name is listed in the Institute’s Book of Honor.

May these few lines be a greeting to Comrade. N. M. Sergeeva from all who know her work well. ”

Scroll another decade with a tail.

February 16, 1962.

A completely different era: the world is dominated by the smile of Gagarin and Fidel Castro’s beard, everyone is discussing the recent rebellion against de Gaulle in Algeria and the exchange of American spy pilot Francis Powers for Soviet intelligence Rudolf Abel. Khrushchev fraternizes with Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, the first episode of the TV show “The Club of the Fun and the Resourceful” aired, the enki and Beatlemania will soon hit the world - after all, the Beatles first recording for the radio just took place in February 62 BBC

And in the newspaper "Steel" there is a note "The Soul of the collective" in the rubric "About good people."

As you can see, here she is already quite a grandmother, but that sincerity of feelings, which is felt well in both notes even through formal words of the time, has remained unchanged. This can not be faked.

It seems that she was really loved and respected. She did not get the easiest time, but she lived, in my opinion, a very decent life.

I don’t know anything more about this woman.

What can I tell you in conclusion, my friends, Internet disputants?

The next time you are going to break your spears, which is better - schoolgirls are ruddy or Soviet public men, remember this note and understand, finally, a simple thing.

These are all the same people.

This is all we.

Volga flows into the Caspian Sea.

History is inextricable.

The same people flow through all regimes and formations - our parents, our grandfathers and grandmothers, our children and our grandchildren.

And the end of this river of time, thank God, is not visible.