It is impossible to exclude an emotional or psychological response to new technologies, especially those related to body modification

With the proliferation of implants, experts are worried about increased surveillance and exploitation of workers. Proponents of technology call these fears irrational.

On August 1, 2017, Three Square Market employees from Wisconsin, a specialist in vending machines, lined up in the company’s canteen for the implantation of a microchip. One by one, they gave their hand to a local tattoo artist who pushed an implant the size of a small picture in their flesh between the thumb and forefinger. 41 employees agreed to the procedure, and all of them received t-shirts with the inscription “I was chipling.”

The wholesale implantation, organized by the company’s management, coincided with the long-term development plan of the company, which includes non-cash payments for their vending machines - so that you can buy a snack at the workplace by simply brushing it. And the advertised “Chipping Party” turned out to be an excellent marketing tactic, and all the media from Moscow to Sydney wrote about this story.

However, not all attention drawn to this event was positive. After that, the authors of some comments on the company’s Facebook page encouraged employees to quit. The company's page on Google was flooded with negative reviews. Christian groups, convinced that the implants fulfill the doomsday prophecy, being the “mark of the beast”, accused the company of belonging to the Antichrist.

Jovan Osterlund, a Swedish tattoo artist and piercer whose company, Biohax, provided the Three Square Market with microchips, watched with interest.

For Osterlund, implants are not something radical or innovative. He has lived with this for many years, and has placed implants in hundreds of other young Swedes who are fond of technology. For this community, the chip stands for a seamless fusion of biology and technology. They used implants to gain access to coworking, pay for gym use, and even train rides. By opening Biohax, Osterlund hoped to bring this concept to the world market.

Three Square Market was an audit, the first company in the United States to publicly offer implants to employees. But the extremely emotional reaction that connected these devices not only with malicious surveillance, but also with ideas about techno-apocalypse, raises a question that Osterlund is still trying to find the answer to: is the world ready to let technology under its skin?

* * *

Microchip implants, in fact, are a cylindrical bar code that, when scanned, transmits a unique signal penetrating through the skin layer. Mostly, these chips are used to organize products, warehouses, recognize livestock and lost pets, although experiments have also been carried out on people.

In 1998, Kevin Warwick , a professor of cybernetics at Reading University, implanted a chip in his hand - both to demonstrate the possibility of the procedure and to study the idea of transhumanism, according to which the fusion of technology with the body is the next step in the evolution of mankind.

Osterlund first heard about microchipping a few years after the start of the Warwick project, when his friend copied his dog’s chip and implanted it under his skin. They both belonged to a body modification lover group in Sweden and often experimented with new technologies such as branding and nasal septum piercing. “The dog’s chip was used for a rally so my friend could go to the vet and pretend to be his own labrador, or something,” Osterlund told me. “But the idea that something more can be done with implants has settled in my head.”

In 2013, Osterlund stumbled upon a German company selling industrial-grade microchips on the Internet. Unlike animals implantable chips capable of transmitting a single identification number, these devices worked with the NFC data transfer protocol, which can be programmed to perform simple tasks.

Osterlund ordered a batch of chips and wrote a simple program, thus connecting his Samsung 5 with a microchip, so that when he took the phone in his hand, he should automatically dial his wife’s number. On the first attempt at implantation, Osterlund accidentally damaged the chip fuse during sterilization. The second attempt succeeded better - when he touched the phone, he automatically started a call to his wife.

“It's like my body went online,” he said. “It was my own moment from Johnny Mnemonic .”

Overjoyed, Osterlund contacted his friend, Hannes Sjoblad, a member of the Swedish transhumanist community. Sioblad was impressed by Osterlund's experiment, and invited him to hold a demonstration at the Epicenter, a technology-co-working coworking in Stockholm, in which Sioblad was "the main one for disintegration."

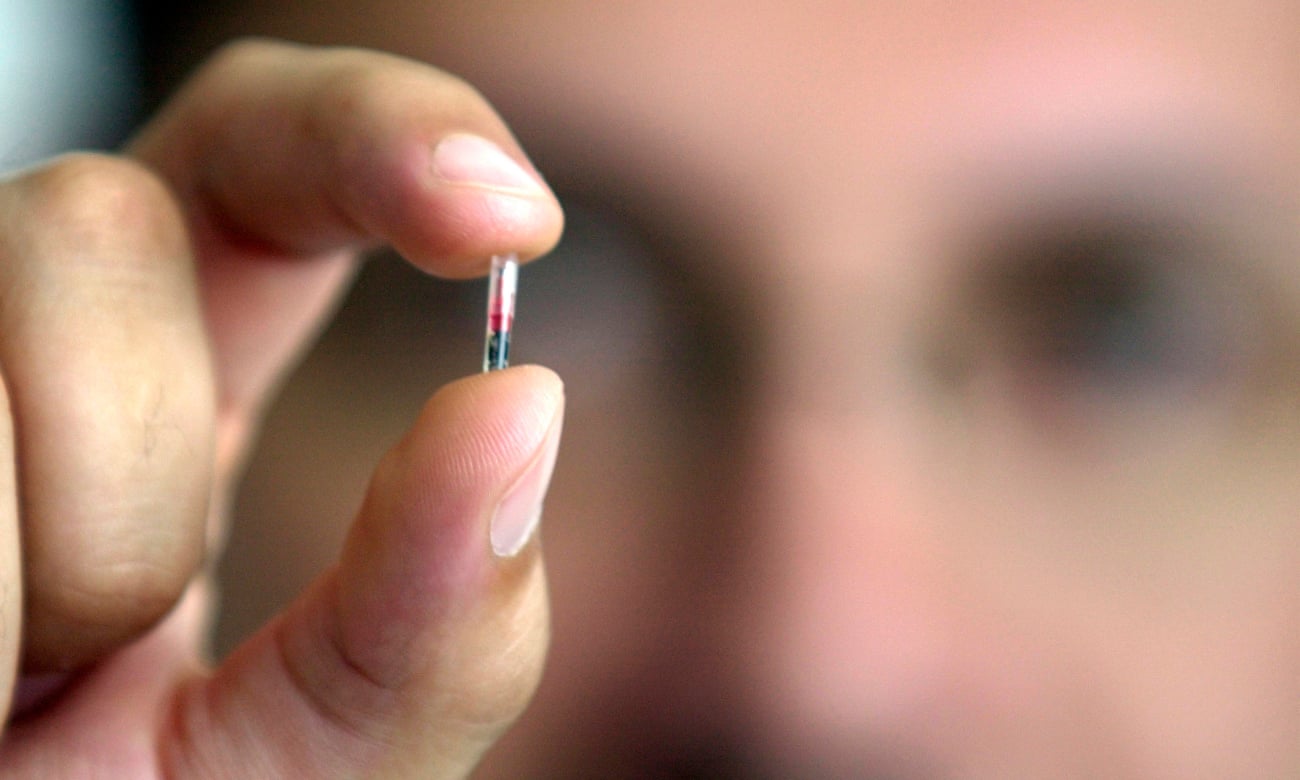

Osterlund holds a microchip implant

Other innovators and founders of the Epicenter startups became interested in the Osterlund implant, and soon they and Sjoblad started organizing “beer with chips” evenings. Osterlund implanted microchips in the process of taking alcoholic beverages and shared ideas about possible uses of cyborg abilities.

"The epicenter was quickly adapted to biochips, and soon we were already opening the front door and printing documents using implants," Syoblad told me. "All this happened on a voluntary basis and was very cool."

* * *

Today, Osterlund and Sjoblad own their own microchip-related enterprises. Osterlund's Biohax aims to simplify identification and access to the digital world, and offers a replacement for endless passwords, keys, tickets and cards that clog our lives. “With the chip, everything is on this one, tiny device that cannot be lost,” he said.

Syoblad’s business, located at a university in southern Sweden, Dsruptive approaches microchipping as an extension of the wearable health device industry. Syoblad believes that by placing the device under the skin, and not wearing it on the arm like Fitibt, you can seriously improve the data collection process. “Swipe an iPhone over it and you’ll get the oxygen content in the blood, temperature profile, patterns of heart rate and respiration,” he said. “For people seeking to optimize their health, this will be a whole new level.”

There are other companies that expand the capabilities of microchip implants, in particular, Seattle's Dangerous Things, which sells a variety of biodevices, including multi-colored LEDs that light under the skin. But Osterlund believes Sweden will become a center of innovation among cyborgs. “The state railway already supports these chips, and our country plans to completely abandon cash by 2023,” he told me. “I think you can see an example of how this can be done here.”

But Urs Gasser, executive director of the Harvard Center for the Internet and the community. Berkman Klein, believes that going beyond the Swedish techno-community to larger markets will be a more complicated process than Osterlund believes, both from a legal and ethical point of view.

“So far, such an experiment has been conducted in a rich country among technically savvy people,” he said. “And if walking with a chip will be convenient for educated people in Sweden who belong to the technical community, the question arises how this will change the situation, say, for workers in a warehouse.”

Gasser believes that many people reacted negatively to the advertised event in Three Square Market because it symbolizes an imbalance of power in the workplace, and provokes anti-utopian images of an authoritarian employer who divorces and strictly controls workers. “Looking at how employees were chipped at work, people wondered what it means to be an employee,” he said. “Is this the person who gets paid for the job, or is it the property of the company he works for?”

Ifeoma Ayunwa, professor of labor and employment laws at Cornell University, adds that it is crucial to evaluate all the consequences of microchipping in the context of increased surveillance of employees. In 2016, “ Unlimited Tracking of Workers, ” Ayunwa et al, Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz, talk about new methods of data collection - Internet history tracking, DNA testing, and collecting health data through health programs on workplace - not only create a more personal profile for employers for each employee, but also leak into their personal and inner lives.

Ayunwa says microchips will deepen and expand this dynamic. They have “the potential for constant and very personal tracking - they literally follow the worker everywhere. This blurs the line between work and family life. ”

* * *

An alarm over the possible implementation of microchipping in the coming years has been shown by several US lawmakers, including Skip Daily, a Democrat from the Nevada State Assembly, who proposed a bill banning forced chip encoding in March. Arkansas, New Jersey and Tennessee are also developing implant laws.

In a press release, Three Square Market emphasized that the "Chipping Party" was completely voluntary. But according to Ayunwe, since labor laws in the US often play into the hands of employers, workers can be coercive in cases involving surveillance.

For example, in 2015, a woman was fired from work after she uninstalled an application to track her movements, although at that time she was not at work. In another recent case, employer requirements for employees to submit their DNA for analysis after human secretions were detected at the workplace were made public . Ayunwa says that in the absence of clear labor regulation prohibiting employees from being monitored, "workers may feel the need to agree to chip, even if in doubt."

Tony Dunn, vice president of Three Square Market, undergoing microchip implantation

When I raised these questions in a conversation with Osterlund, he said that in order to successfully scale up the microchip procedure, it would be necessary to create new legal platforms, in particular regarding voluntary consent. He believes that microchiping in Sweden is partly successful due to clear laws governing labor and data protection, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which creates an atmosphere of trust between government and society, the employer and the employee.

However, both he and Sjoblad suggest that for the most part the fear caused by microchipping is based not so much on a concern for privacy, but on an irrational prejudice against implants. “The microchips are intrinsic and passive, in fact, they are magnetic cards that cannot be lost,” Osterlund said. “So it seems ironic to me when people with an iPhone and a Gmail account express concern on privacy on Facebook just because they are afraid of injections.”

It is impossible to exclude an emotional or psychological response to new technologies, especially those associated with body modification. Gasser believes that this emotional response should not be immediately rejected, calling it superstitious or illogical. “The fear we feel about microchips is associated not so much with a certain technology as with technology in the context of power and unequal power structures, such as the relationship between employer and employee,” he said. “And when this dynamics is built into our bodies, we cross a certain tangible line.”