JavaScript innovations: Google I / O 2019 results. Part 2

Today we are publishing the second part of the translation of JavaScript innovations. Here we talk about separators of digits of numbers, about BigInt-numbers, about working with arrays and objects, about

, about sorting, about the internationalization API and about promises.

→ The first part

Long numbers found in programs are hard to read. For example,

is one billion in decimal. But at a glance it’s hard to understand. Therefore, if the reader of the program encounters something similar - he, in order to correctly perceive it, will have to carefully consider zeros.

In modern JavaScript, you can use the separator of digits of numbers - the underscore (

), the use of which improves the readability of long numbers. Here's how numbers written using a delimiter look in code:

Separators can be used for arbitrary division of numbers into fragments. JavaScript, when dealing with numbers, simply ignores separators. They can be used when writing any numbers: integers, floating point, binary, hexadecimal, octal.

Numbers in JavaScript are created using the

constructor function.

The maximum value that can be safely represented using the

data type is (2⁵³ - 1), that is, 9007199254740991. You can see this number using the

construct.

Please note that when a numeric literal is used in JS code, JavaScript processes it, creating an object based on it using the

constructor. The prototype of this object contains methods for working with numbers. This happens with all primitive data types .

What will happen if we try to add something to the number 9007199254740991?

The result of adding

and 10, the second output of

, is incorrect. This is due to the fact that JS cannot correctly perform calculations with numbers greater than the value of

. You can deal with this problem by using the

data

.

The

type allows

to represent integers that are greater than

. Working with BigInt values is similar to working with values of type

. In particular, the language has the function

, with which you can create the corresponding values, and the built-in primitive data type

, used to represent large integers.

JavaScript adds

to the end of BigInt literals. For us, this means that such literals can be written by adding

to the end of integers.

Now that we have BigInt numbers at our disposal, we can safely perform mathematical operations on large numbers of type

.

A number of type

is not the same as a number of type

. In particular, we are talking about the fact that BigInt-numbers can only be integers. As a result, it turns out that arithmetic operations that use the

and

types cannot be performed.

It should be noted that the

function can take various numbers: decimal, binary, hexadecimal, octal. Inside this function, they will be converted to numbers, the decimal number system is used to represent them.

The

type also supports bit separators:

Here we’ll talk about the new prototype methods for the

object — the

and

methods.

Now objects of type

have a new method -

. It returns a new array, allowing recursively to raise the elements of arrays to the specified level

. By default,

is 1. This method can be passed

equal to

, which allows you to convert an array with nested arrays into a one-dimensional array.

When solving everyday tasks, the programmer may sometimes need to process the array using the

method with its subsequent transformation into a flat structure. For example, create an array containing the numbers and squares of these numbers:

The solution to this problem can be simplified by using the

method. It converts the arrays returned by the callback function passed to it in the same way that it would convert their

method with parameter

equal to 1.

You can extract

type pairs from an object

can be used using the static

method, which returns an array, each element of which is an array containing, as the first element, a key, and as the second - a value.

Now we have at our disposal a static method

, which allows us to convert a similar structure back into an object.

The

method was used to facilitate filtering and mapping of data stored in objects. The result is an array. But so far, the task of converting such an array into an object has not had a beautiful solution. It is for solving this problem that you can use the

method.

If the

data structure is used to store the pairs

, then the data in it is stored in the order they were added to it. At the same time, how the data is stored resembles the array returned by the

method. The

method is

easy to use for transforming

data structures into objects.

We are familiar with the

used in JavaScript. It does not have some fixed value. Instead, the meaning of

depends on the context in which it is accessed. In any environment, the

points to a global object when it is accessed from the context of the highest level. This is the global meaning of

.

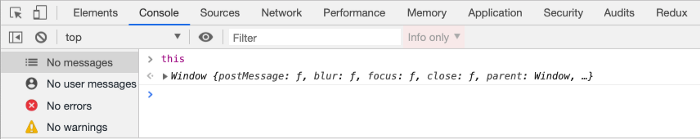

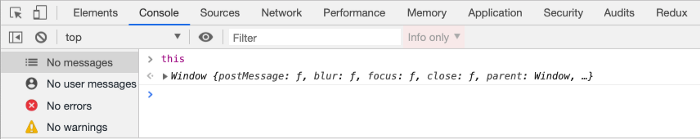

In browser-based JavaScript, for example, the global value for

is the

object. You can verify this by using the

construct at the top level of the JavaScript file (in the most external context) or in the browser JS console.

Accessing this in the browser console

The global value of

in Node.js points to a

object. Inside a web worker, it points to the worker himself. However, getting the global

value is not an easy task. The fact of the matter is that you cannot access

anywhere. For example, if you try to do this in the constructor of the class, it turns out that

points to an instance of the corresponding class.

In some environments, you can use the

keyword to access the global value of

. This keyword plays the same role as the mechanisms for accessing this value in browsers, in Node.js, and in web workers. Using knowledge of how the global value of

is called in different environments, you can create a function that returns this value:

Before us is a primitive polyfill to get the global

object. Read more about this here . JavaScript now has the

keyword. It provides a universal way of accessing the global value of

for different environments and does not depend on the location of the program from which it is accessed.

The ECMAScript standard does not offer a specific array sorting algorithm that JavaScript engines should implement. It only describes the API used for sorting. As a result, using different JS engines, one may encounter differences in the performance of sorting operations and in the stability (stability) of sorting algorithms.

Now the standard requires that sorting arrays be stable. Details on sorting stability can be found here . The essence of this characteristic of sorting algorithms is as follows. The algorithm is stable if the sorting result, which is a modified array, contains elements with the same values that were not affected by the sorting in the same order in which they were placed in the original array. Consider an example:

Here, the

array containing the objects is sorted by the

field of these objects. In the

array, an object with the

property equal to

is located before the object with the

property equal to

. Since the

values of these objects are equal, we could expect that in the sorted array these elements will retain the previous arrangement order relative to each other. However, in practice it was impossible to count on this. How exactly the sorted array will be formed depended entirely on the JS engine used.

Now all modern browsers and Node.js use a stable sorting algorithm, called when accessing the

array method. This allows you to always, for the same data, get the same result:

In the past, some JS engines supported stable sorting, but only for small arrays. To increase productivity when processing large arrays, they could take advantage of faster algorithms and sacrifice sort stability.

The internationalization API is designed to organize string comparisons, to format numbers, dates, and times as is customary in various regional standards (locales). Access to this API is organized through the

object . This object provides constructors for creating sorter objects and objects that format data. The list of locales supported by the

object can be found here .

In many applications, it is often necessary to output the time in a relative format. It may look like “5 minutes ago,” “yesterday,” “1 minute ago,” and so on. If the website materials are translated into different languages, you have to include all possible combinations of relative constructions describing the time in the site assembly.

JS now has the

constructor , which allows you to create date and time formatting systems for different locales. In particular, we are talking about objects that have a method

, which allows you to generate various relative timestamps. It looks like this:

The

constructor allows

to combine list items using the words

(

) and

(

). When creating the corresponding object, the constructor is passed the locale and the object with the parameters. Its

parameter can be

,

and

. For example, if we want to combine the elements of

using a conjunction object, we get a string of the form

. If you use a disjunction object, we get a string of the form

.

The object created by the

constructor has a

method that combines lists. Consider an example:

The concept of “regional standard” is usually much more than just the name of a language. This may include the type of calendar, information about the time cycles used, and the names of languages. The

constructor

used to create formatted

strings based on the

object passed to it.

object created using

contains all the specified regional settings. Its

method produces a formatted regional standard string.

Here you can read about identifiers and locale tags in Unicode.

Currently, JS has the static methods

and

. The

method returns a promise that is successfully resolved after all the promises passed to the method as an argument are resolved. This promise is rejected in the event that at least one of the promises transferred to it is rejected. The

method returns a promise, which is resolved after any of the promises transferred to it is resolved, and is rejected if at least one of such promises is rejected.

The community of JS developers was desperate for a static method, the promise returned that would be resolved after all the promises passed to it would be complete (allowed or rejected). In addition, we needed a method similar to

, which would return a promise waiting for the resolution of any of the promises passed to it.

The

method accepts an array of promises. The promise returned by him is permitted after all the promises are rejected or permitted. The result is that the promise returned by this method does not need a

.

The fact is that this promise is always successfully resolved. The

block receives

and

from each promise in the order they appear.

The

method is similar to

, but the promise returned by it does not execute the

when one of the promises passed to this method is rejected.

Instead, he awaits the resolution of all promises. If no promises were allowed, then the

block will be executed. If any of the promises is successfully resolved,

will be executed.

In this article, we looked at some of the JavaScript innovations discussed at the Google I / O 2019 conference. We hope you find something among them that is useful to you.

Dear readers! What do you especially miss in JavaScript?

globalThis

, about sorting, about the internationalization API and about promises.

→ The first part

Number Separators

Long numbers found in programs are hard to read. For example,

1000000000

is one billion in decimal. But at a glance it’s hard to understand. Therefore, if the reader of the program encounters something similar - he, in order to correctly perceive it, will have to carefully consider zeros.

In modern JavaScript, you can use the separator of digits of numbers - the underscore (

_

), the use of which improves the readability of long numbers. Here's how numbers written using a delimiter look in code:

var billion = 1_000_000_000; console.log( billion ); // 1000000000

Separators can be used for arbitrary division of numbers into fragments. JavaScript, when dealing with numbers, simply ignores separators. They can be used when writing any numbers: integers, floating point, binary, hexadecimal, octal.

console.log( 1_000_000_000.11 ); // 1000000000.11 console.log( 1_000_000_000.1_012 ); // 1000000000.1012 console.log( 0xFF_00_FF ); // 16711935 console.log( 0b1001_0011 ); // 147 console.log( 0o11_17 ); // 591

→ Support

- TC39: Stage 3

- Chrome: 75+

- Node: 12.5+

Bigint data type

Numbers in JavaScript are created using the

Number

constructor function.

The maximum value that can be safely represented using the

Number

data type is (2⁵³ - 1), that is, 9007199254740991. You can see this number using the

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER

construct.

Please note that when a numeric literal is used in JS code, JavaScript processes it, creating an object based on it using the

Number

constructor. The prototype of this object contains methods for working with numbers. This happens with all primitive data types .

What will happen if we try to add something to the number 9007199254740991?

console.log( Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER ); // 9007199254740991 console.log( Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 10 ); // 9007199254741000

The result of adding

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER

and 10, the second output of

console.log()

, is incorrect. This is due to the fact that JS cannot correctly perform calculations with numbers greater than the value of

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER

. You can deal with this problem by using the

bigint

data

bigint

.

The

bigint

type allows

bigint

to represent integers that are greater than

Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER

. Working with BigInt values is similar to working with values of type

Number

. In particular, the language has the function

BigInt()

, with which you can create the corresponding values, and the built-in primitive data type

bigint

, used to represent large integers.

var large = BigInt( 9007199254740991 ); console.log( large ); // 9007199254740991n console.log( typeof large ); // bigint

JavaScript adds

n

to the end of BigInt literals. For us, this means that such literals can be written by adding

n

to the end of integers.

Now that we have BigInt numbers at our disposal, we can safely perform mathematical operations on large numbers of type

bigint

.

var large = 9007199254740991n; console.log( large + 10n ); // 9007199254741001n

A number of type

number

is not the same as a number of type

bigint

. In particular, we are talking about the fact that BigInt-numbers can only be integers. As a result, it turns out that arithmetic operations that use the

bigint

and

number

types cannot be performed.

It should be noted that the

BigInt()

function can take various numbers: decimal, binary, hexadecimal, octal. Inside this function, they will be converted to numbers, the decimal number system is used to represent them.

The

bigint

type also supports bit separators:

var large = 9_007_199_254_741_001n; console.log( large ); // 9007199254741001n

→ Support

New Array Methods: .flat () and .flatMap ()

Here we’ll talk about the new prototype methods for the

Array

object — the

.flat()

and

.flatMap()

methods.

▍ .flat () method

Now objects of type

Array

have a new method -

.flat(n)

. It returns a new array, allowing recursively to raise the elements of arrays to the specified level

n

. By default,

n

is 1. This method can be passed

n

equal to

Infinity

, which allows you to convert an array with nested arrays into a one-dimensional array.

var nums = [1, [2, [3, [4, 5]]]]; console.log( nums.flat() ); // [1, 2, [3, [4,5]]] console.log( nums.flat(2) ); // [1, 2, 3, [4,5]] console.log( nums.flat(Infinity) ); // [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

→ Support

▍ .flatMap () method

When solving everyday tasks, the programmer may sometimes need to process the array using the

.map()

method with its subsequent transformation into a flat structure. For example, create an array containing the numbers and squares of these numbers:

var nums = [1, 2, 3]; var squares = nums.map( n => [ n, n*n ] ) console.log( squares ); // [[1,1],[2,4],[3,9]] console.log( squares.flat() ); // [1, 1, 2, 4, 3, 9]

The solution to this problem can be simplified by using the

.flatMap()

method. It converts the arrays returned by the callback function passed to it in the same way that it would convert their

.flat()

method with parameter

n

equal to 1.

var nums = [1, 2, 3]; var makeSquare = n => [ n, n*n ]; console.log( nums.flatMap( makeSquare ) ); // [1, 1, 2, 4, 3, 9]

→ Support

▍ Object.fromEntries () Method

You can extract

:

type pairs from an object

:

can be used using the static

Object

method, which returns an array, each element of which is an array containing, as the first element, a key, and as the second - a value.

var obj = { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3 }; var objEntries = Object.entries( obj ); console.log( objEntries ); // [["x", 1],["y", 2],["z", 3]]

Now we have at our disposal a static method

Object.fromEntries()

, which allows us to convert a similar structure back into an object.

var entries = [["x", 1],["y", 2],["z", 3]]; var obj = Object.fromEntries( entries ); console.log( obj ); // {x: 1, y: 2, z: 3}

The

entries()

method was used to facilitate filtering and mapping of data stored in objects. The result is an array. But so far, the task of converting such an array into an object has not had a beautiful solution. It is for solving this problem that you can use the

Object.fromEntries()

method.

var obj = { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3 }; // [["x", 1],["y", 2],["z", 3]] var objEntries = Object.entries( obj ); // [["x", 1],["z", 3]] var filtered = objEntries.filter( ( [key, value] ) => value % 2 !== 0 // , ); console.log( Object.fromEntries( filtered ) ); // {x: 1, z: 3}

If the

Map

:

data structure is used to store the pairs

:

, then the data in it is stored in the order they were added to it. At the same time, how the data is stored resembles the array returned by the

Object.entries()

method. The

Object.fromEntries()

method is

Object.fromEntries()

easy to use for transforming

Map

data structures into objects.

var m = new Map([["x", 1],["y", 2],["z", 3]]); console.log( m ); // {"x" => 1, "y" => 2, "z" => 3} console.log( Object.fromEntries( m ) ); // {x: 1, y: 2, z: 3}

→ Support

▍ Global property globalThis

We are familiar with the

this

used in JavaScript. It does not have some fixed value. Instead, the meaning of

this

depends on the context in which it is accessed. In any environment, the

this

points to a global object when it is accessed from the context of the highest level. This is the global meaning of

this

.

In browser-based JavaScript, for example, the global value for

this

is the

window

object. You can verify this by using the

console.log(this)

construct at the top level of the JavaScript file (in the most external context) or in the browser JS console.

Accessing this in the browser console

The global value of

this

in Node.js points to a

global

object. Inside a web worker, it points to the worker himself. However, getting the global

this

value is not an easy task. The fact of the matter is that you cannot access

this

anywhere. For example, if you try to do this in the constructor of the class, it turns out that

this

points to an instance of the corresponding class.

In some environments, you can use the

self

keyword to access the global value of

this

. This keyword plays the same role as the mechanisms for accessing this value in browsers, in Node.js, and in web workers. Using knowledge of how the global value of

this

is called in different environments, you can create a function that returns this value:

const getGlobalThis = () => { if (typeof self !== 'undefined') return self; if (typeof window !== 'undefined') return window; if (typeof global !== 'undefined') return global; if (typeof this !== 'undefined') return this; throw new Error('Unable to locate global `this`'); }; var globalThis = getGlobalThis();

Before us is a primitive polyfill to get the global

this

object. Read more about this here . JavaScript now has the

globalThis

keyword. It provides a universal way of accessing the global value of

this

for different environments and does not depend on the location of the program from which it is accessed.

var obj = { fn: function() { console.log( 'this', this === obj ); // true console.log( 'globalThis', globalThis === window ); // true } }; obj.fn();

→ Support

Stable sorting

The ECMAScript standard does not offer a specific array sorting algorithm that JavaScript engines should implement. It only describes the API used for sorting. As a result, using different JS engines, one may encounter differences in the performance of sorting operations and in the stability (stability) of sorting algorithms.

Now the standard requires that sorting arrays be stable. Details on sorting stability can be found here . The essence of this characteristic of sorting algorithms is as follows. The algorithm is stable if the sorting result, which is a modified array, contains elements with the same values that were not affected by the sorting in the same order in which they were placed in the original array. Consider an example:

var list = [ { name: 'Anna', age: 21 }, { name: 'Barbra', age: 25 }, { name: 'Zoe', age: 18 }, { name: 'Natasha', age: 25 } ]; // age [ { name: 'Natasha', age: 25 } { name: 'Barbra', age: 25 }, { name: 'Anna', age: 21 }, { name: 'Zoe', age: 18 }, ]

Here, the

list

array containing the objects is sorted by the

age

field of these objects. In the

list

array, an object with the

name

property equal to

Barbra

is located before the object with the

name

property equal to

Natasha

. Since the

age

values of these objects are equal, we could expect that in the sorted array these elements will retain the previous arrangement order relative to each other. However, in practice it was impossible to count on this. How exactly the sorted array will be formed depended entirely on the JS engine used.

Now all modern browsers and Node.js use a stable sorting algorithm, called when accessing the

.sort()

array method. This allows you to always, for the same data, get the same result:

// [ { name: 'Barbra', age: 25 }, { name: 'Natasha', age: 25 } { name: 'Anna', age: 21 }, { name: 'Zoe', age: 18 }, ]

In the past, some JS engines supported stable sorting, but only for small arrays. To increase productivity when processing large arrays, they could take advantage of faster algorithms and sacrifice sort stability.

→ Support

- Chrome: 70+

- Node: 12+

- Firefox: 62+

Internationalization API

The internationalization API is designed to organize string comparisons, to format numbers, dates, and times as is customary in various regional standards (locales). Access to this API is organized through the

Intl

object . This object provides constructors for creating sorter objects and objects that format data. The list of locales supported by the

Intl

object can be found here .

▍Intl.RelativeTimeFormat ()

In many applications, it is often necessary to output the time in a relative format. It may look like “5 minutes ago,” “yesterday,” “1 minute ago,” and so on. If the website materials are translated into different languages, you have to include all possible combinations of relative constructions describing the time in the site assembly.

JS now has the

Intl.RelativeTimeFormat(locale, config)

constructor , which allows you to create date and time formatting systems for different locales. In particular, we are talking about objects that have a method

.format(value, unit)

, which allows you to generate various relative timestamps. It looks like this:

// español ( ) var rtfEspanol= new Intl.RelativeTimeFormat('es', { numeric: 'auto' }); console.log( rtfEspanol.format( 5, 'day' ) ); // dentro de 5 días console.log( rtfEspanol.format( -5, 'day' ) ); // hace 5 días console.log( rtfEspanol.format( 15, 'minute' ) ); // dentro de 15 minutos

→ Support

▍Intl.ListFormat ()

The

Intl.ListFormat

constructor allows

Intl.ListFormat

to combine list items using the words

and

(

) and

or

(

). When creating the corresponding object, the constructor is passed the locale and the object with the parameters. Its

type

parameter can be

conjunction

,

disjunction

and

unit

. For example, if we want to combine the elements of

[apples, mangoes, bananas]

using a conjunction object, we get a string of the form

apples, mangoes and bananas

. If you use a disjunction object, we get a string of the form

apples, mangoes or bananas

.

The object created by the

Intl.ListFormat

constructor has a

.format(list)

method that combines lists. Consider an example:

// español ( ) var lfEspanol = new Intl.ListFormat('es', { type: 'disjunction' }); var list = [ 'manzanas', 'mangos', 'plátanos' ]; console.log( lfEspanol.format( list ) ); // manzanas, mangos o plátanos

→ Support

▍Intl.Locale ()

The concept of “regional standard” is usually much more than just the name of a language. This may include the type of calendar, information about the time cycles used, and the names of languages. The

Intl.Locale(localeId, config)

constructor

Intl.Locale(localeId, config)

used to create formatted

Intl.Locale(localeId, config)

strings based on the

config

object passed to it.

Intl.Locale

object created using

Intl.Locale

contains all the specified regional settings. Its

.toString()

method produces a formatted regional standard string.

const krLocale = new Intl.Locale( 'ko', { script: 'Kore', region: 'KR', hourCycle: 'h12', calendar: 'gregory' } ); console.log( krLocale.baseName ); // ko-Kore-KR console.log( krLocale.toString() ); // ko-Kore-KR-u-ca-gregory-hc-h12

Here you can read about identifiers and locale tags in Unicode.

→ Support

- TC39: Stage 3

- Chrome: 74+

- Node: 12+

Promises

Currently, JS has the static methods

Promise.all()

and

Promise.race()

. The

Promise.all([...promises])

method returns a promise that is successfully resolved after all the promises passed to the method as an argument are resolved. This promise is rejected in the event that at least one of the promises transferred to it is rejected. The

Promise.race([...promises])

method returns a promise, which is resolved after any of the promises transferred to it is resolved, and is rejected if at least one of such promises is rejected.

The community of JS developers was desperate for a static method, the promise returned that would be resolved after all the promises passed to it would be complete (allowed or rejected). In addition, we needed a method similar to

race()

, which would return a promise waiting for the resolution of any of the promises passed to it.

▍ Promise.allSettled () Method

The

Promise.allSettled()

method accepts an array of promises. The promise returned by him is permitted after all the promises are rejected or permitted. The result is that the promise returned by this method does not need a

catch

.

The fact is that this promise is always successfully resolved. The

then

block receives

status

and

value

from each promise in the order they appear.

var p1 = () => new Promise( (resolve, reject) => setTimeout( () => resolve( 'val1' ), 2000 ) ); var p2 = () => new Promise( (resolve, reject) => setTimeout( () => resolve( 'val2' ), 2000 ) ); var p3 = () => new Promise( (resolve, reject) => setTimeout( () => reject( 'err3' ), 2000 ) ); var p = Promise.allSettled( [p1(), p2(), p3()] ).then( ( values ) => console.log( values ) ); // [ {status: "fulfilled", value: "val1"} {status: "fulfilled", value: "val2"} {status: "rejected", value: "err3"} ]

→ Support

▍ Method Promise.any ()

The

Promise.any()

method is similar to

Promise.race()

, but the promise returned by it does not execute the

catch

when one of the promises passed to this method is rejected.

Instead, he awaits the resolution of all promises. If no promises were allowed, then the

catch

block will be executed. If any of the promises is successfully resolved,

then

will be executed.

Summary

In this article, we looked at some of the JavaScript innovations discussed at the Google I / O 2019 conference. We hope you find something among them that is useful to you.

Dear readers! What do you especially miss in JavaScript?

All Articles