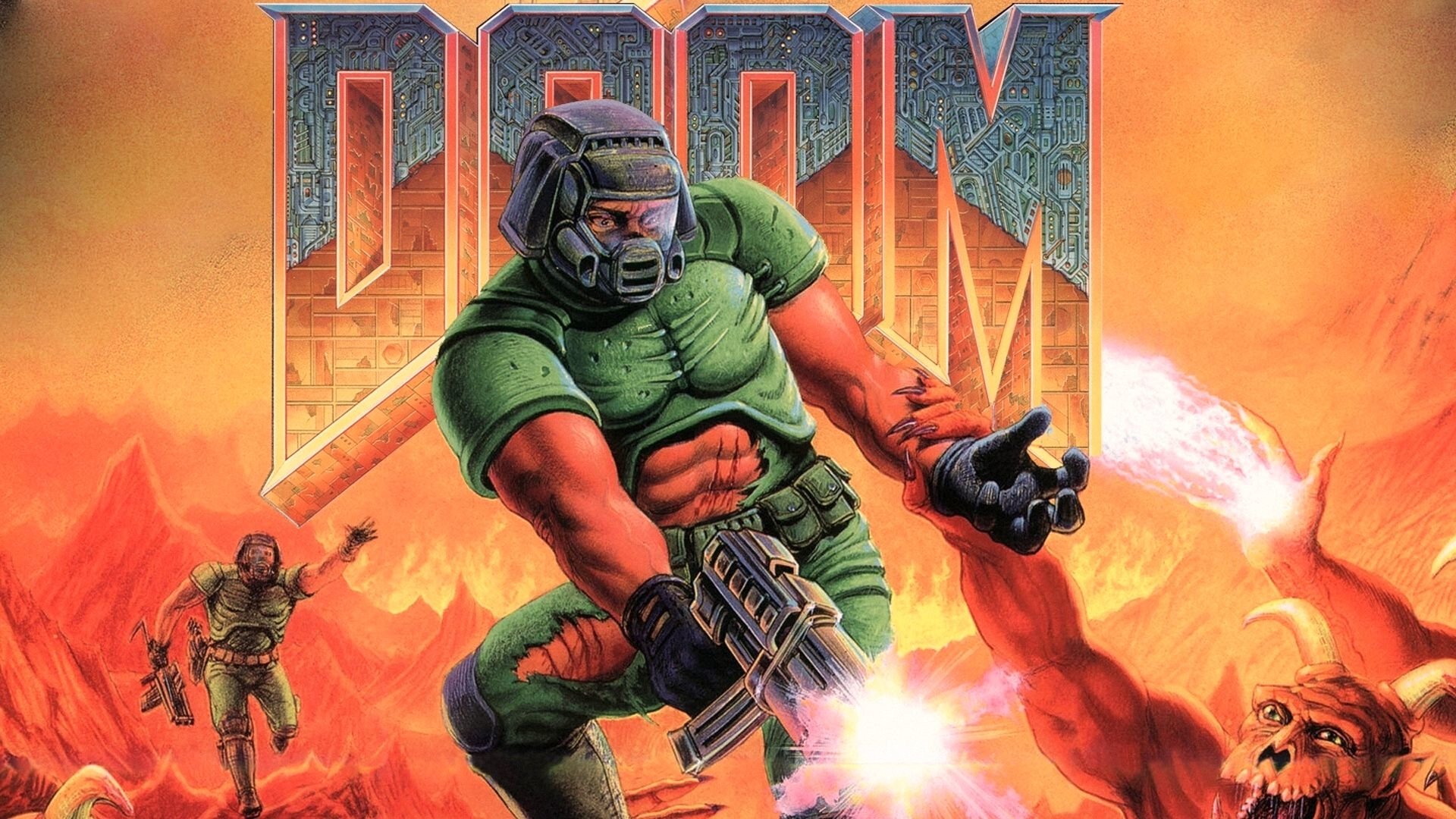

How many games have gained such popularity that they were installed on more computers than Microsoft Windows?

They have been studying the success and impact of DOOM on the industry for more than 25 years, trying to understand what is special about this title in 1993. You can talk about DOOM endlessly: starting with technical achievements, speedrans, mods and ending with the level design of the game. This will not fit into any article.

Better to see what lessons action games can learn from DOOM: good and bad.

Level design and authorship

Fights in DOOM are shooting demons on the move at the speed of light. On the levels you can find closed doors, hidden places and secret rooms with weapons. Everything is seasoned with backtracking, which is why these levels seem very open. You cannot look up or down, and since you often have to rely on auto-guidance, you can say that DOOM is tied to finding the right location and speed. Each level is harder than the previous one. And the difficulty reaches its peak by the end of the game, when the user has to look for a way out of the miniature labyrinth of death.

These levels are part of the first lesson. Initially, the locations were to be developed by game designer Tom Hall, but they seemed too weak to the programmer John Romero. In particular, due to the fact that they did not use all available technologies . Unlike previous games of the company, for example, Wolfenstein 3D, in DOOM it was necessary to include various levels of elevation above the ground, curved corridors, the ability to play with ambient light and a bunch of other chips.

3D rendering of the location E1M1. The work of Ian Albert .

It is these elements that distinguish DOOM levels against the backdrop of modern games and even surpass many of them. The most famous example is Episode 1, Mission 1: Hangar [E1M1], created by John Romero. You find yourself in a horseshoe-shaped room with a ladder, go into the corridor, then the path wags in a zigzag pattern around the acid pool. After which you see a seemingly unattainable place that beckons with super armor.

All this does not look so epic as in 1993, but the mood is just that , especially for action games. In most action games, you find yourself in an open space with rare corridors. Usually there are no elevations in them, except for a small rock on which you can jump. Modern technologies that allow you to use interesting types of geometry or wrestling - for example, the ability to walk on the ceiling, as in Prey (2006), fly, as in DarkVoid (2010), or grab a hook, like in Sekiro, are tied to the context, ignored or reduced to minor tricks, instead of playing a key role in game design. Technology is advancing and giving us many opportunities that seem to have turned games towards simplification.

John Romero was a programmer, but independently developed the design of the E1M1. DOOM levels were collected from ready-made assets, so one person could make them. Romero worked independently and became the almost sole author of the levels. It is this authorial approach that lacks modern level design.

Doom made six people . Programmers John Carmack, John Romero, Dave Taylor, artists Adrian Carmack (not a relative of John), Kevin Cloud and game designer Sandy Petersen, who replaced Tom Hall ten weeks before the release.

For comparison: take one of the recent releases - Devil May Cry 5 (2019). 18 game designers, 19 environment artists, 17 interface artists, 16 character artists, more than 80 animators, over 30 VFX and lighting artists, 26 programmers and 45 developers on the engine worked on it. Not to mention those who worked with sound, cinematics and all outsourcing tasks, for example, character rigging. In total, more than 130 people worked on the product alone, almost three times more than on the first Devil May Cry in 2001. But management, marketing and other departments were still involved in the process.

1993 Doom Team

A small part of the Devil May Cry 5 team

Why it happens? Because of the visual part, creating games today takes a lot more power than before. The reason for this is the transition to a 3D picture, which means more complicated rigging, advanced motion capture technologies, an increase in frame rate and resolution, as well as an increase in the complexity of the code and engines that handle all this. Productive equipment is needed, and the result is more error-prone and less flexible. For example, the King of Fighters XIII title team, which is built on sprites, took about 16 months to make one single character. The creators of the project had to deal with several heroes at the same time and crunch in order to be in time for release. The requirements for how a paid game should look have grown significantly . A striking example of this is the negative reaction of fans to Mass Effect: Andromeda.

Perhaps it was the desire to meet the ever-changing standards of cool visuals that put the author’s eye on the background. And although there are people in the industry like Kamiya (Resident Evil, Bayonetta), Jaffe (God of War, Twisted Metal) and Ansel (Rayman, Beyond Good & Evil), they are more likely managers who monitor the image of the product, rather than those who independently create a whole bunch of levels.

Yes, for example, Director Itagaki personally supervised the work on most of the fights in Ninja Gaiden II. But, despite all the enthusiasm, one person no longer makes a change. One gear drives the other, then another, and more, and more.

If Director Itsuno wanted to remake an entire mission in the last ten weeks of Devil May Cry 5, it would be a huge task. By comparison, Sandy Petersen was able to do 19 of 27 DOOM levels ten weeks before the release. Even 8 are based on Tom Hall's sketches.

At the same time, they had their own atmosphere, thanks to Petersen's love for the theme of the levels. The theme was a kind of dividing line in the game. For example, there was a level based on exploding barrels (DOOM II, Map23: Barrels o 'Fun). Another example is how Romero focused on contrast. Light and shadow, limited space and open. Thematic levels flowed into each other, and users had to return to already completed areas in order to build a map in their head.

In simple words, game design has become too complex a mechanism and has lost the flexibility that it had at the time of DOOM in 1993.

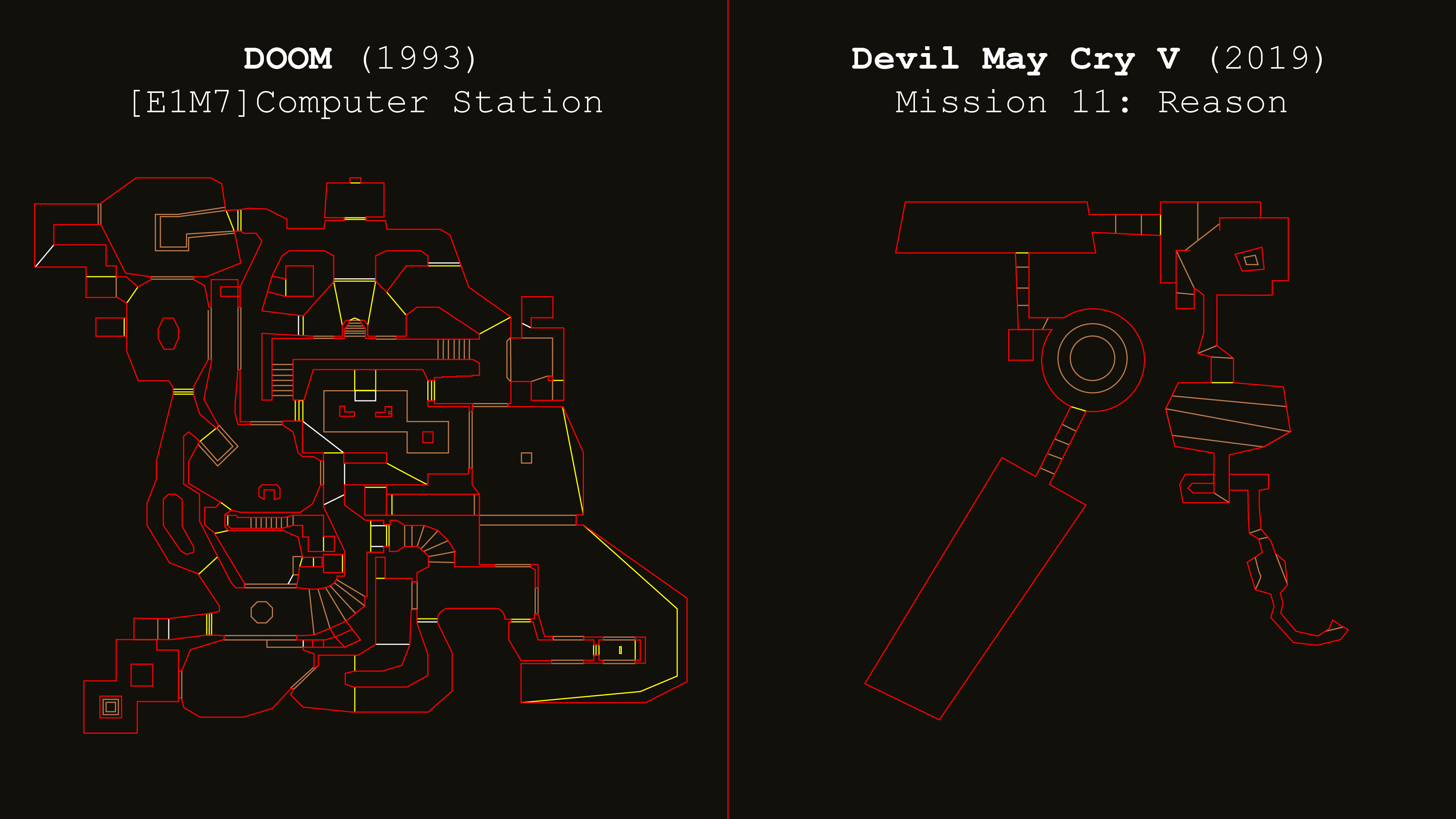

Most levels of modern action games consist of open space and simple forms, if you look at them from above. Strong art and complex effects hide this simplicity, and the plot or interesting battles fill it. Games rely more on the current gameplay than on the levels in which the action takes place.

Illustration of Stinger Magazine; ClassicDoom color palette. The Mission 11 map is based on video footage, so forgive us for the lack of some details. But hope the idea is clear.

The DOOM level design also has its drawbacks; its quality is not always up to par. The first levels of the first episode of Knee Deep in the Dead (“Knee-deep in Corpses”) were almost completely designed by Romero. But later add-ons came out and the game became like a mishmash of several designers. Sometimes it was necessary to pass cards from four different designers in a row: each of them is of a different quality, philosophy and logic. As a result, the game can hardly be called whole.

However, here is the first lesson that modern action games can learn:

Modern action games focus on the current gameplay, rather than where the action is. Level design should cover all technical achievements in order to offer users new types of levels, interesting ways to overcome obstacles, gameplay or battle scenarios. At the same time, you need to avoid advertising tricks and stay true to your vision of the project. Open space is cool, but it should be used less often.

Technology has become too complex and focused on detail, and one person can no longer create a level. It all comes down to battles and art. It would be great to see an action title that cares less about texture resolution or physicality of fabrics and is more focused on the flexibility of game design. In order for the design to be integral, unlike DOOM, the game must have a leading designer who monitors the consistency of levels.

The relationship of enemies and weapons

Passing levels is determined by what opponents the player meets and what kind of weapon kills them. Enemies in DOOM move and attack in different ways, some can even be used to kill others. But the fights there are so good, therefore. Pinky's only goal is to pounce on you and bite you. Imp periodically throws fireballs. So far, everything is simple.

However, if Imp joins the fight with Pinky, everything changes. If earlier you just had to keep your distance, now you also have to dodge fireballs. Add lava around the arena and things will change even more. Twelve more steps, and we get a multi-level foundation of the arena, various types of enemies acting together - all in all, to constantly generate unique situations for a player who is on the alert all the time because of the environment.

Each demon in DOOM has its own special feature. This allows you to create exciting situations in battles with enemies of various types . And everything becomes even more interesting when you take into account the player’s weapon.

In the first mission of each episode, all collected weapons are reset. The distribution of weapons that can be obtained in certain missions, even more affects the battle. The battle with the three Barons of Hell will take place differently, not only depending on the room in which it will unfold, but also on whether you received the Plasma Cannon or you only have a regular shotgun.

Later battles in the game, as a rule, turn into mass battles. Point skirmishes are replaced by waves of enemies, especially in the third episode of DOOM and the second half of DOOM II. Most likely, the designers wanted to compensate for the growth of the player’s skill and increase the power of the weapon. Plus, DOOM usually reveals all its cards quite early. Most enemies are already found in the first half of the game, and at further levels, DOOM developers are experimenting with what is already there. As a result, all possible combinations were realized, and the levels began to copy each other or rely on such tricks as hordes of enemies. Sometimes these decisions give interesting experiences, and sometimes they just inflate the game.

Battles also vary depending on the level of difficulty. In Ultra Violence mode, in one of the key locations you can find Kakodemona who spits with clots of plasma, which completely changes the dynamics of the game. Enemies and their shells accelerate on Nightmare difficulty, plus killed enemies respawn after a certain period of time. In all difficulty modes, objects are located at different points and there is a unique weapon. Good example: Episode 4, Mission 1: Hell Beneath [E4M1]. The author of this mission, American McGee, removed all first-aid kits in Ultra Violence and Nightmare modes, making the already difficult level the most difficult in the entire DOOM series. And John Romero, by the way, removed some light sources in Episode 1, Mission 3: Toxic Refinery [E1M3], to make it harder to see opponents.

This approach allows level designers to create different versions of the same level with unique opponents, given the player’s skills.

Consider the addition of The Plutonia Experiment, developed by the brothers Dario and Milo Casali. In one of the missions, the player encounters nine Archwiles (these are some of the most dangerous enemies). For comparison: in DOOM II there is only one battle with two Archwiles almost at the very end of the game. Cyberdemon (the boss from the second episode of DOOM) was used in the same way - it was not easy to go through a battle with him. In Plutonia, a player encounters four such monsters at once.

Dario officially stated that the addition was made for those who completed DOOM II on Hard and want to get a more complex mode, in which the most extreme conditions are recreated using familiar elements. He went through the game at maximum difficulty and modified too simple levels. He also added that he did not sympathize with players who complained that Plutonia was too complicated in Hard mode.

Images cannot do justice to The Plutonia Experiment. So enjoy the video reflecting all the unreality of this add-on. Posted by: Civvie11 .

Focusing not only on hardcore players, DOOM also uses difficulty levels to make it easier for beginners to get used to the game. The player gets into less difficult battles with less dangerous enemies and gets more first-aid kits or finds powerful weapons earlier. DOOM doesn’t babysit players with such changes as Vanquish, Resident Evil 2 Remake, the ability to transfer control to the game (Bayonetta 2) or automatic dodge (Ninja Gaiden 3). Such changes do not increase your skill, they just play in your place.

Obviously, DOOM seeks to bring even the smallest element of the game to perfection. This is the second lesson for action games:

Most modern action games have already laid the foundation for a good game: a large set of enemies, the actions that a player can perform, and their relationship. But all this is taken for granted. But you can experiment with what combination of opponents and abilities the user sees. The enemy must not only be brought into the game, but also developed. You can try to create various settings and a unique level design, so that the enemy is felt every time in a new way. Combine opponents who have no reason to unite, and if there is a risk that the immersion in the game world will be violated, leave such unique battles only at high levels of difficulty. If your game is too difficult, add a simpler mode to make it easier for beginners to get comfortable.

Use different combinations of enemies and weapons. Do not be afraid to increase the number of difficulty levels to introduce new more dangerous battles or to puzzle users with a new arrangement of objects. You can even let players create their own cards. The developers of Trials of Lucia for the game Dante's Inferno correctly grasped this idea, but poorly implemented it. Who knows how cool battles can unfold if users can create them themselves? Just look at the endless creative process that gives players Super Mario Maker.

Movement in an action game

A key element of all collisions in DOOM is movement. Your location, the location of the enemy, and how you can bridge the distance between you. In addition to the standard features, action games offer a huge number of other options for moving. The ability to run around walls in Ninja Gaiden, abrupt sidestepping in Shinobi and teleportation to Devil May Cry 3. However, all these movements are static, even the attack of the hero is static.

When Dante attacks, he cannot move, just like Ryu loses his mobility the second he prepares his blade. There are attacks that make it possible to move, for example, Windmill Slash in Ninja Gaiden or Stinger in Devil May Cry 3. But they are usually predetermined: the movement is mainly necessary for fast dodging or moving a certain distance at a certain angle. And then the attack continues from the moment at which it stopped.

These games offer a bunch of tricks to attack and attack the opponent so as to stay face to face with him. A sharp contrast with DOOM, where movement and movement are associated with the attack key, which is logical, given the genre of the game. In addition, most of the hidden mechanics of the game are related to speed and mobility - for example, SR50, Strafe Running, Gliding and Wall Running.

This is not to say that this is not implemented in action games. Players can move during an attack in The Wonderful 101, and there is also Raiden's Ninja Run in Metal Gear Rising: Revengeance. In some games, movement is an opportunity that a weapon gives, for example, Tonfa in Nioh (you can cancel the movement by pressing a button). But in general, despite the 2D brothers like Ninja Gaiden III: The Ancient Ship of Doom or Muramasa: The Demon Blade, in modern action games, the movement in battle looks rather unnatural.

In Devil May Cry 4, players can use the inertia of previously canceled attacks for subsequent movement, giving them the ability to move during combat, often called Inertia. An example is Guard Flying. This ability was removed in Devil May Cry 5, which legitimately led to controversy and discussion, because a significant number of attacking mechanics were removed along with it. This emphasizes how important it is for people to navigate this way in the game.

So why is this almost unique element used in DOOM 2016, Vanquish, Max Payne 3 and Nelo not implemented in games that so extol mobility, such as Shinobi or even Assassin's Creed?

One answer to this question: such mobility can make the game too simple. In Metal Gear Rising, enemies automatically parry attacks after blocking a certain number of strokes to prevent the player from completely blocking them with Ninja Running.

Another argument against mobility: attacks will seem less powerful. Despite the fact that mobility does not affect the mechanics, the entertainment of an attack consists of various elements: waiting for animation, duration, body movement and enemy reaction. The attack in motion will lack animation, it will look less clear, and in the end the movement will seem to be floating.

In order for everything to look right, enemies must influence the process, but this, of course, will not happen. Opponents are created to defeat them, with rare exceptions. In DOOM II, the Archwiles demons appear in sight, you need to run from the shotguns to locations, and Pinki should beware in confined spaces. Such changes in the design of enemies allow action games to create opponents who dodge the attack much more often or use movements in the line of sight (for example, the gaze of Nure-Onna in Nioh 2).

An interesting project: an action game in which the attack is only part of the whole, and the constant movement, control and exact position of the hero during this attack are as important as she herself.

The third lesson (and the last). More precisely, not even a lesson, but a spark of inspiration:

Too many action games restrict movement during an attack. If 2D games were built on movement in battle, now the movement takes place until you join the battle. When attacking, you stop, and only move when you start to defend.

Action games can grow by experimenting with movement at the time of the battle and how it combines with various types of enemies. It should become a full-fledged game mechanics of this genre not only when evading attacks, it should also work in attack. It doesn’t matter if the movement is realized through a unique weapon or the whole game will be built on it.

Conclusion

There are other lessons that can be learned from DOOM. For example, how levels are filled with secrets that motivate you to study the location. How replenishment of the armor with small fragments rewarded these studies. How the screen with the results motivated to perform all tasks at the level. Or how the study of the hidden mechanics of beams at BFG made it possible to play at a higher level. You can also learn from mistakes. Avoid duplication of certain types of weapons, boring boss fights and stupid change of level aesthetics, as in DOOM II. You can find inspiration in DOOM 2016. In particular, it shows how to properly upgrade weapons.

It is important to remember that all these lessons are generalized - they cannot be used in every game or in every style. Old games in the Resident Evil series don't need extra mobility during battles. And these lessons do not guarantee sales growth.

The general conclusion is this:

Action games have been around for a very long time, but since the release of PlayStation 2 they gradually came to a template created thanks to Rising Zan and subsequently secured by the Devil May Cry franchise. Let this article serve as an incentive for finding new elements and exploring unexplored prospects that will help make games more seamless and interesting.

Additional Information

- Initially, I planned to just write a DOOM review. But it seemed to me that there were already too many of them and it was unlikely that I could add anything new, besides my assessment of the game. And I wrote this article. I think it turned out well, I was able to do a review, give the most positive assessment of DOOM, and suggest ways to improve modern action games.

- The main artist of the environment Devil May Cry 5 is called Shinji Mikami. Not to be confused with Shinji Mikami.

- Initially, I wanted to take the opportunity to gradually restore armor in a separate lesson, but then I decided to abandon it, since it is not significant enough. The idea is that usually DOOM armor restores your armor to 100 units, no more. However, small pieces of armor can make up for it up to 200 units - the game is full of secret places where they can be found. This is a pretty easy way to reward the user with something useful for research. Something similar is in the title of Viewtiful Joe, in each chapter of which you need to collect containers for the film to upgrade your VFX-meter.

- I practically didn’t mention the battles between the enemies, because the article was getting too long. This is found in some action games - in Asura's Wrath, enemies can damage each other.

- I wanted to mention Sieg from Chaos Legion, Akira from Astral Chain, and V from Devil May Cry 5 in the movement tutorial. I always liked the ability to summon monsters to attack while you move. However, these characters suffer the same limitations when they begin to attack, so I decided to lower them so as not to confuse anyone. In addition, there are enough examples in that part of the article.

- Initially, Nightmare was added to DOOM to eliminate all possible complaints that Ultra Violence is too simple. As a result, the majority considered him overwhelming, although this mode of difficulty still has its loyal fans.

- The way in DOOM the enemies and the arrangement of objects in more complex game modes change, is fully implemented only in Ninja Gaiden Black. In this game, along with complexity, enemies change, the arrangement of objects, scarab rewards and even new bosses are introduced. At each level of difficulty, you seem to be passing a new game. In some modes, you have to engage in more serious fights than in more complex modes, respectively, you need to somehow compensate for the damage received. And Ninja Dog mode forces players to evolve, instead of babysitting with them. I recommend reading a cool article on this topic from action-brother Shane Eric Dent.

- I wrote a detailed analysis of why John Romero's E1M2 is such a cool level, and why I consider his card to be the best in the entire DOOM series, but I did not find where to insert this material. I have not edited it. Maybe one day. The same story with the analysis of opponents in DOOM II.

- The name of the game itself is usually written in capital letters - DOOM, while the builder is called - Doom. It pains me to look at such a discrepancy, but it’s so customary.

- Yes, American McGee is a real name. He himself comments on it this way: “Yes, that's what my mother called me. According to her, she was inspired by a college friend who gave her daughter the name America. She also said that she was thinking of calling me Obnard. She has always been a very eccentric and creative person. ”

- It is sad that most modern action games are farther and farther removed from the combination of various types of enemies. In Ninja Gaiden II, you will never meet the demons Van Gelf and the ninja from Spider Clan at the same time. Just like Dark Souls veterans will not run into Phalanx, which is assisted by enemies like Undead Archer and Ghost. Modern titles prefer to stick to a certain topic, and mixing unrelated enemies can disrupt the effect of immersion. It's a pity.

- For this article, I decided to test Doom Builder myself. Despite the fact that he is not completed, it is interesting to see how just one monster Lost Soul can change the entire course of the battle. Particularly cool is how the struggle between the enemies themselves can affect the atmosphere of the whole battle. Here is a link to the levels, just do not judge strictly, they are not too good.

Sources

- https://pastebin.com/1ds4rUsh

- https://www.reddit.com/r/IAmA/comments/3t1obw/sandy_petersen_designer_of_cthulhu_wars_DOOM_call/

- https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/131767/secrets_of_the_sages_level_design.php?print=1

- https://www.helldoradoteam.com/2018/12/19/john-romeros-level-design-tips/

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YUU7_BthBWM

- Masters of DOOM - David Kushner (ISBN13: 9780812972153)

- https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/198783/monsters_from_the_id_the_making_.php

- https://www.pcgamesn.com/making-doom-ids-shooter-masterpiece

- https://doomwiki.org/wiki/Doom_Builder

- https://web.archive.org/web/20061030081729/

- http://www.americanmcgee.com/forum/index.php?board=3.0

- https://www.doomworld.com/forum/topic/87199-the-doom-movement-bible/