My name is Alexander Denisov. I work for Naumen and am responsible for documenting and localizing the Naumen Contact Center (NCC) software product.

In this article I will talk about the problems that we encountered when localizing NCC in English and German and how we solved these problems. Of course, today we have solved far from all of our tasks, and most likely this process is generally endless. The article considers the vision of the whole process as a whole and those principles that we try to adhere to or that we are starting to try to apply. The material will be useful to those who are just starting to design software, plan to localize it or are already facing problems, but do not yet know how to solve them.

Introduction

Often a company thinks about software localization when the product is ready and documentation has been written for it. And it is also often too late to do something in order to get good localization in a short time and not spend a huge amount of resources on it.

It is impossible to write in detail about all the problems and difficulties in one article, so I will talk a little about the main stages of documentation and localization and touch on several, in my opinion, the most important issues:

- What stages of the software development life cycle affect the quality of documentation and localization?

- What and when to do at each stage?

- What approaches, capabilities of tools can be applied to solve problems and problems of each stage?

- Like an org. Does structure affect documentation and localization processes?

- How to organize receiving feedback from users of the documentation?

- How to save time and financial costs at each stage?

Based on my many years of experience in documenting and localizing NCC, I will try to answer these questions.

Features of NCC and the development process

Naumen Contact Center is a sophisticated software for organizing large corporate or outsourcing contact centers.

What is the difficulty of documenting and localizing this system:

- The system is not cloudy.

- Complex setup, many integrations with various systems.

- Support for multiple versions.

- As a result of paragraphs 1-3, we have complex implementations and updates. Each client has its own version, its own configuration and integration with various systems.

- The system is not massive; it is used only by big business. Therefore, the number of customers is not very large compared to small mass products.

- A large number of specific terms.

- Multi-role model. And this means that the documentation and interface should be tailored to the characteristics of each role (level of knowledge and features of tasks).

- System interfaces contain about 30,000 lines of text and about 3,000 pages of complex technical documentation are written.

- Releases are released 2-3 times a year.

- After each release, approximately 10% of the interface text and documentation are updated and supplemented.

- 3 languages: Russian (source), English and German.

Development life cycle

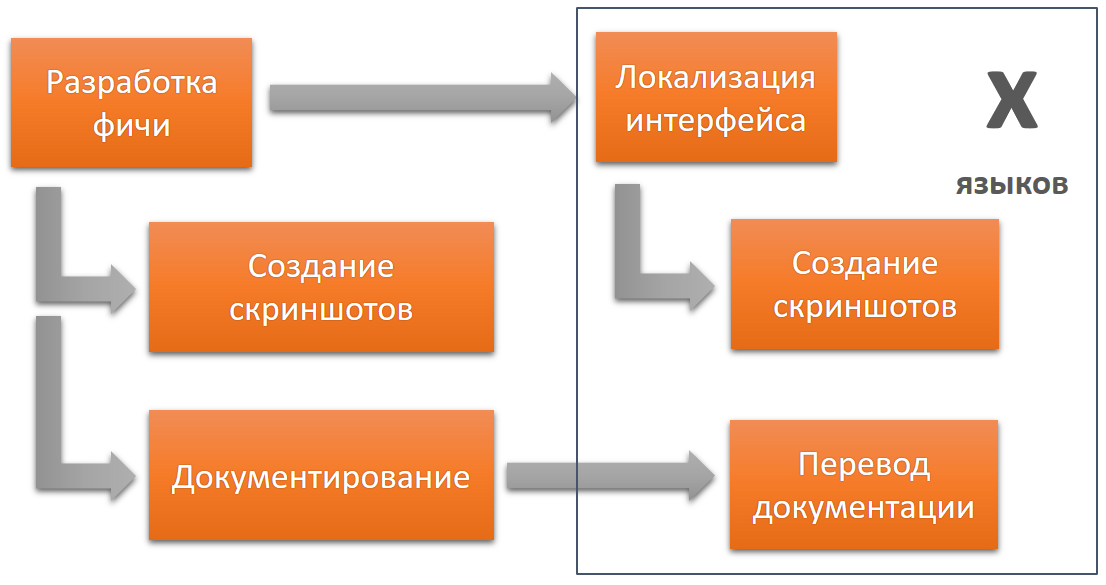

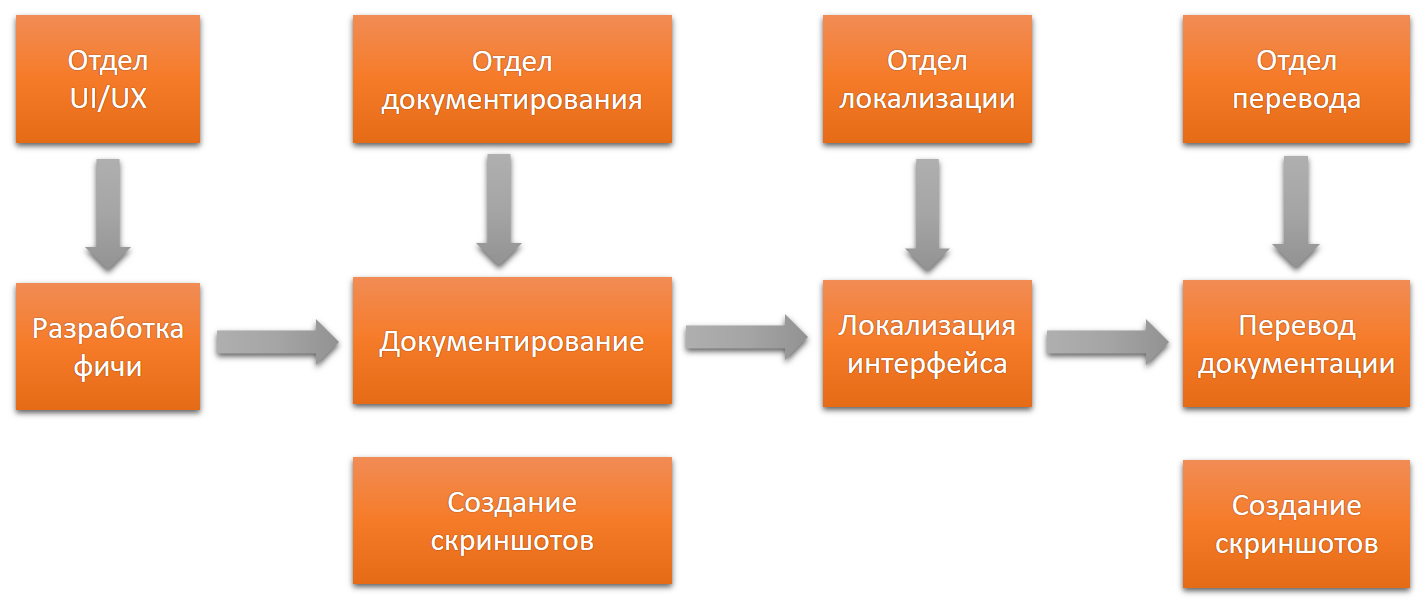

Let's look at the life cycle of software development and highlight only those stages that relate to documentation and localization:

- Feature development. As part of this phase, texts for the interface are developed.

- Documentation As part of this phase, documentation is developed, including the creation of screenshots and other images.

- Localization of the interface in several languages.

- Translation of documentation into other languages, including localization of screenshots and other images.

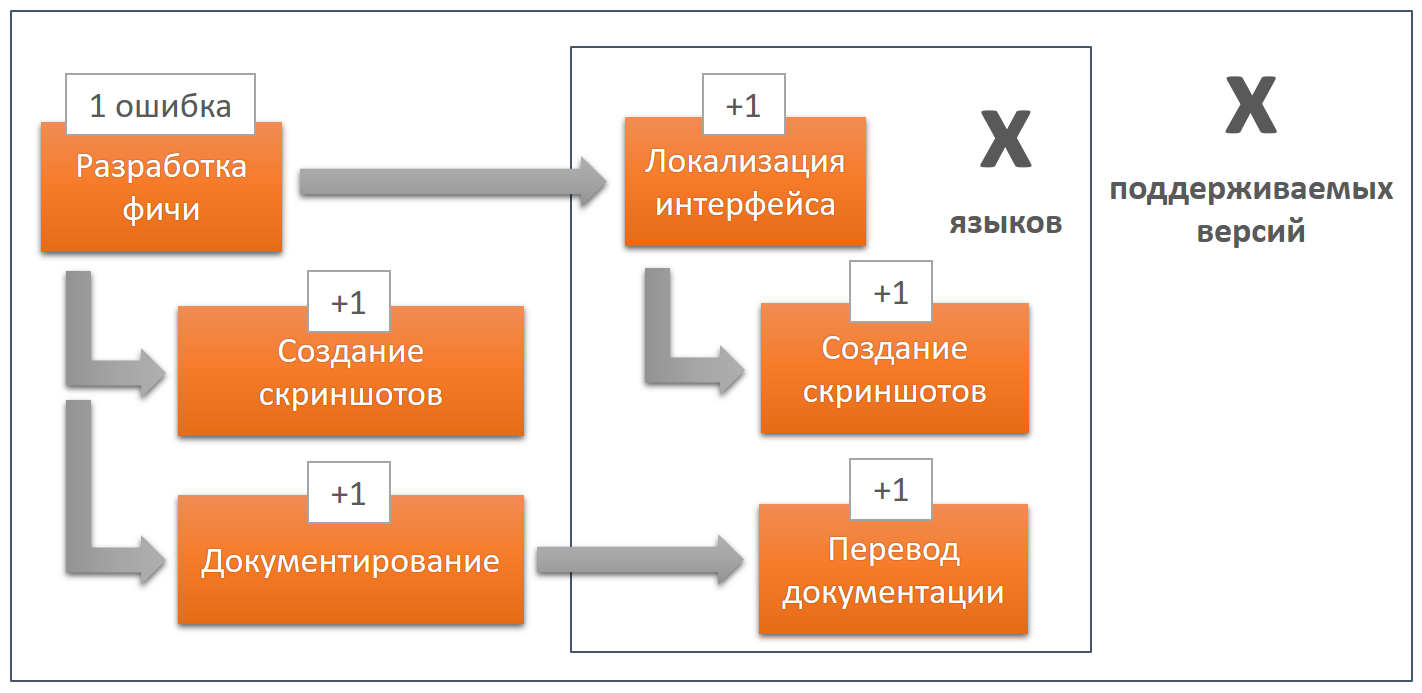

Now let's imagine that one minor mistake was made in the interface. It automatically applies to each stage, to several versions and languages.

Additional errors may appear at each stage, that is, as a result, we can get a huge number of errors. Minor interface errors will most likely never be fixed; there are always more important tasks. And if you edit them, then the cost of these edits will be very high, since you will again have to go through the whole chain, all versions and languages. And the more versions and languages, the more expensive.

In this context, one cannot talk only about the quality of localization of the interface or about the quality of the translated documentation, since the result of the work of each stage is the foundation for the next stage. That is why it is very important to immediately do everything right at each stage. And that is why it is worth considering software development, documentation and localization as stages of a single inextricable process.

Organization of text in the interface

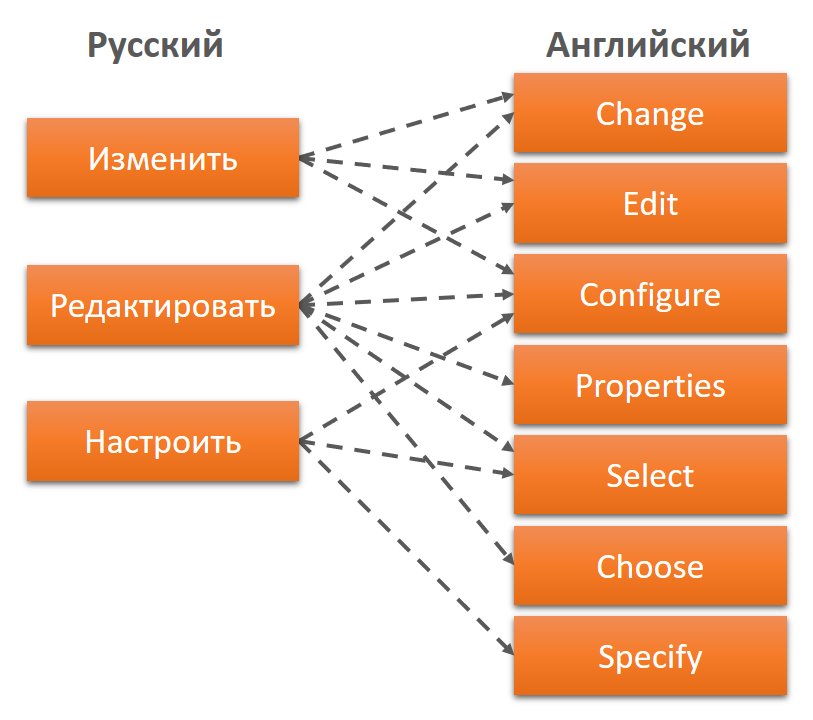

When our programmers took up the localization of the system, it was absolutely not ready for this. The text of the interface was stored in the code, and the desire of the leadership was: "do everything quickly." The programmers wrote a script that pulled out all the text from the code and threw it into the resource files, and the next day they gave the resource files to the first employee who knew English, who quickly translated everything in notepad. What came of this can be seen below.

The image shows a simple button, it opens some form with parameters, where these parameters can be changed. There are dozens of such buttons in the system. In Russian, there were 3 options for such a button; localization into English already contained 7 options.

In this situation, immediately there is a great desire to clean up the lines of the interface. To do this, I propose to apply the following rules:

- Division of all lines into groups.

All lines should be divided into groups according to the type of interface elements. Even if the lines have the same text, different translation rules may apply for different groups. For example, the capitalization rule for the first letter of each word in English. For some types of interface elements, it is used, for others not. - Removing duplicates.

In each group, it makes sense to delete all duplicate lines, that is, lines with the same text. Then there will remain the only option both in Russian and in other languages. This saves translation costs. I note that most likely the repeated lines will still remain, since in some cases the context may be different. Moreover, such lines with the same source text can be translated in different ways. For example, the word Name , in the context of a person’s name can be translated as First name , and in the context of a file name, simply Name . - Adding context to line identifiers.

The line identifier may consist of the identifier of the line itself and the group to which the line belongs. This is necessary so that the translator can use the identifier to select a localization rule. If we have such correct identifiers, then the process of checking and correcting the same capitalization errors can be easily automated.

Unfortunately, applying these rules to all existing 30,000 lines at once is very time consuming. Here we are at the initial stage and gradually put in order the most frequently repeated lines and develop rules for new lines. But you must admit, it would be great if all the rules were spelled out and implemented immediately!

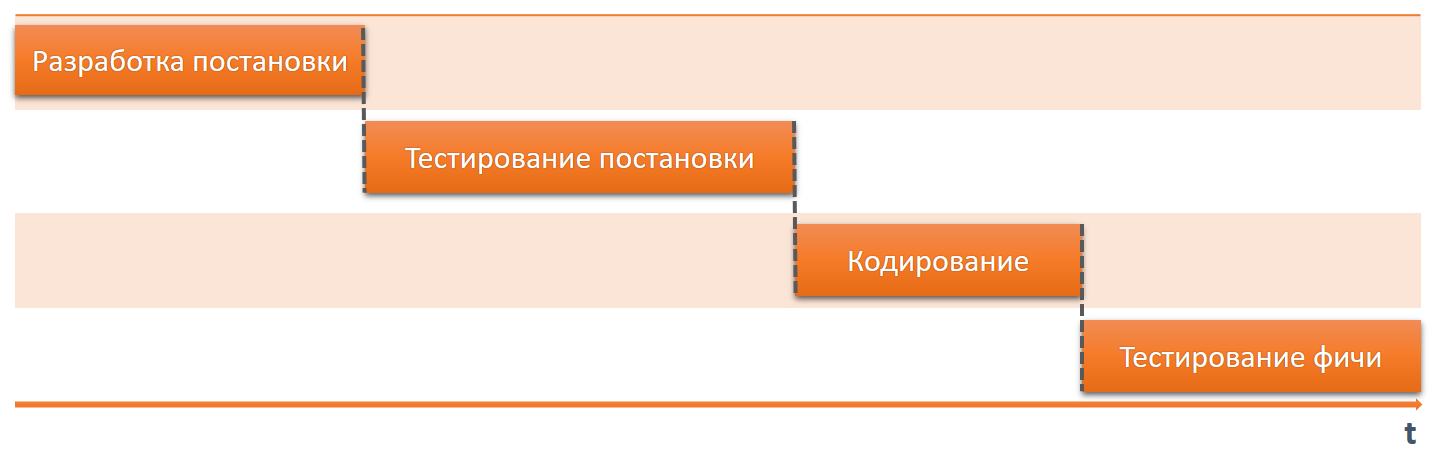

Documentation and Localization Process

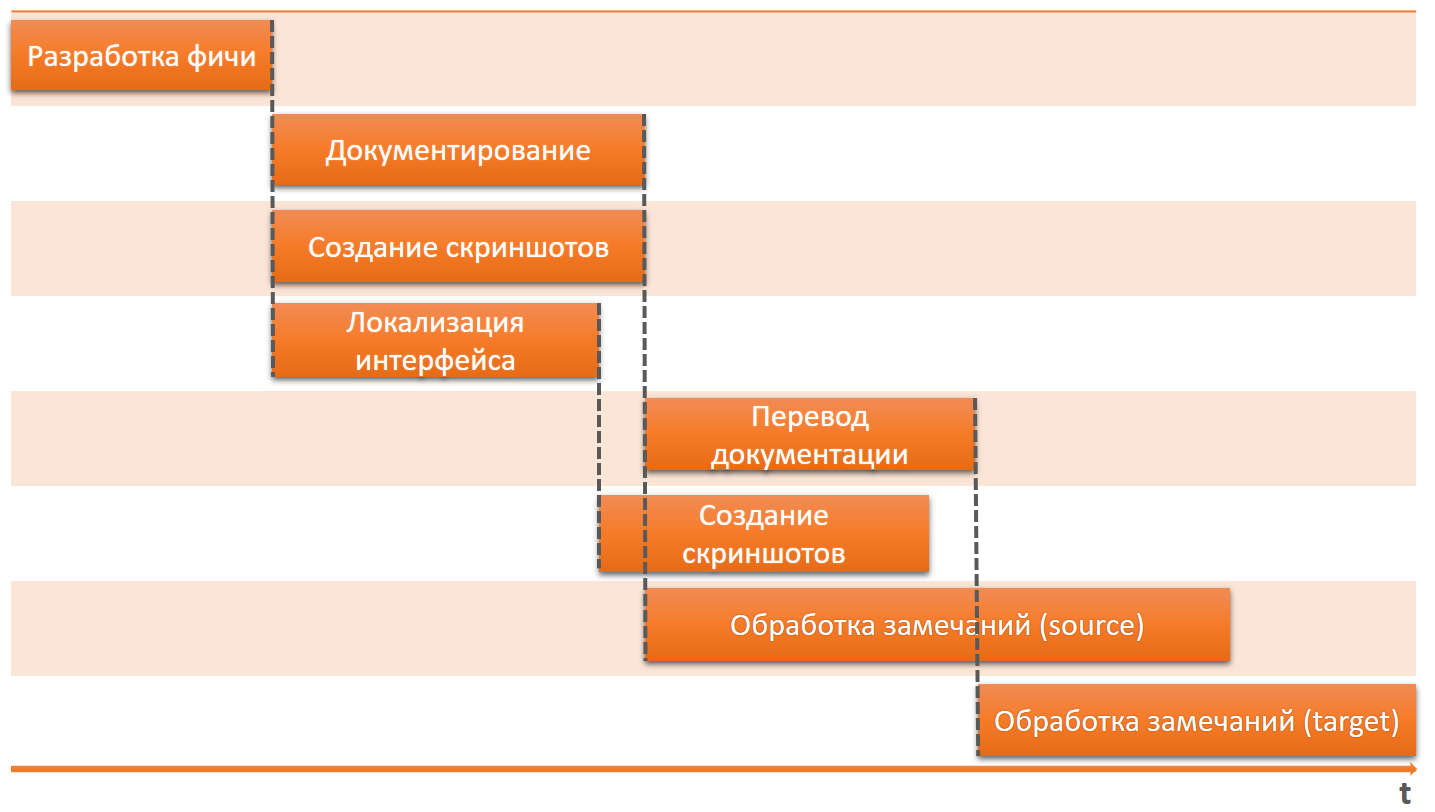

Let's take a look at the time-based documentation and localization process. If you start documenting and localizing before the feature development has finished, you will have to redo everything (maybe several times).

Same thing with translating documentation.

And if you give the documentation to users before all the edits have ended, you can count on a bunch of comments. Most likely, some of these comments will be corrected at the last stages of development, but you will have to spend extra time to process them.

If the processes are not coordinated, and we do not track all the changes on time, then “nothing-nothing-anywhere” will not correspond.

The documentation will not match the interface. Screenshots will not match the interface and the text of the documentation.

The same with localization. The text of the interface and documentation in the source language will not match the text of the interface and documentation in other languages.

We decided that at the moment we can afford to start each new stage only after we have finished the previous one.

Yes, the documentation and localization with us come out late after the release. And if we talk about localization, we have already secured the possibility of continuous localization, but we do not use this opportunity and do all the localization in one step at the end of the release. A couple of days as part of a semi-annual release is a very small stage.

While our product is not massive, we do not have an urgent need for documentation and localization to appear on the same day. We have long releases, large corporate clients, of which there are not very many in comparison with small and more massive products, and they do not immediately begin to install a new version of the product or upgrade to it. The costs of constant remodeling are noticeably reduced.

Terminology issues

At the stage of documentation and localization, we constantly faced problems with terminology:

- The same entities were called differently, and different entities were named the same.

- The same terms were translated differently, and different terms were translated the same way.

- An entity could be equated with its child entities of which it consists, or parent entities.

- Unsuccessful or incorrect terms were chosen to denote an entity.

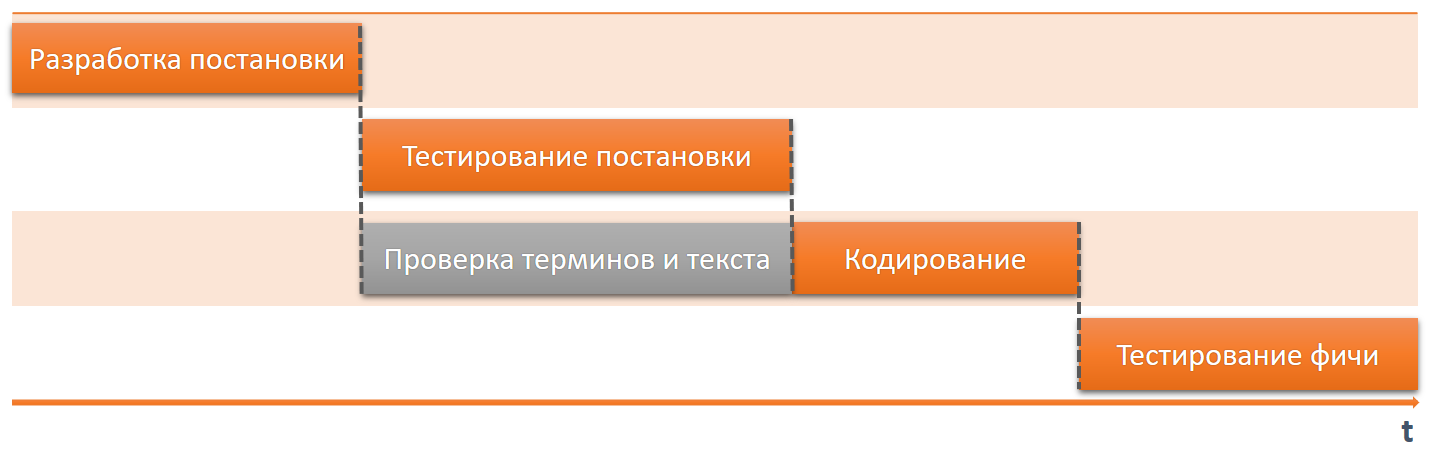

The development process for us for some time looked like this:

- Analysts are writing a production.

- Testers test the production.

- Developers code.

- Testers test the result.

And when trying to wedge into this process with terminology, we received such excuses:

- You will slow down the whole process.

- This is generally not so important.

- You have the tools, you can fix everything later.

But "later" it turned out that we can not fix everything. For example, there were situations when, due to incorrectly understood terminology, system objects were placed at the wrong hierarchy levels or were combined into incorrect groups.

Now we are checking terms and interface text in parallel with setting testing. That is, while testers write their comments, we write our own.

What we do during production testing:

- We reveal new terms.

- Check the text of the interface: for the correct use of terms, compliance with the style guide and compliance with the roles.

- We identify existing lines so as not to make duplicates.

- We agree on the need for localization, since some parts of the interface can be used only in one country.

When revealing new terms, we add them to the glossary, while:

- Add a definition or context.

- We indicate the relationship with other terms (indicate parent and child terms).

- We are trying to immediately indicate the English meaning, since after choosing the English name it sometimes becomes clear that the Russian is not chosen very correctly.

We can say that due to the coordination of terminology and interface texts at the stage of setting approval, we began to save a lot of time on multiple corrections in the subsequent stages.

Documentation

The principles that we adhere to when documenting:

- Using a single source system.

- Using the glossary.

- Use the style guide.

- Division of documentation into small and easily alienable documents.

This is worth doing, even if the main format is the Web. If necessary, you can not translate all the documentation, but only the most important documents, or do it in stages.

Now I’ll talk about some of the most important aspects of the documentation process.

Reuse text

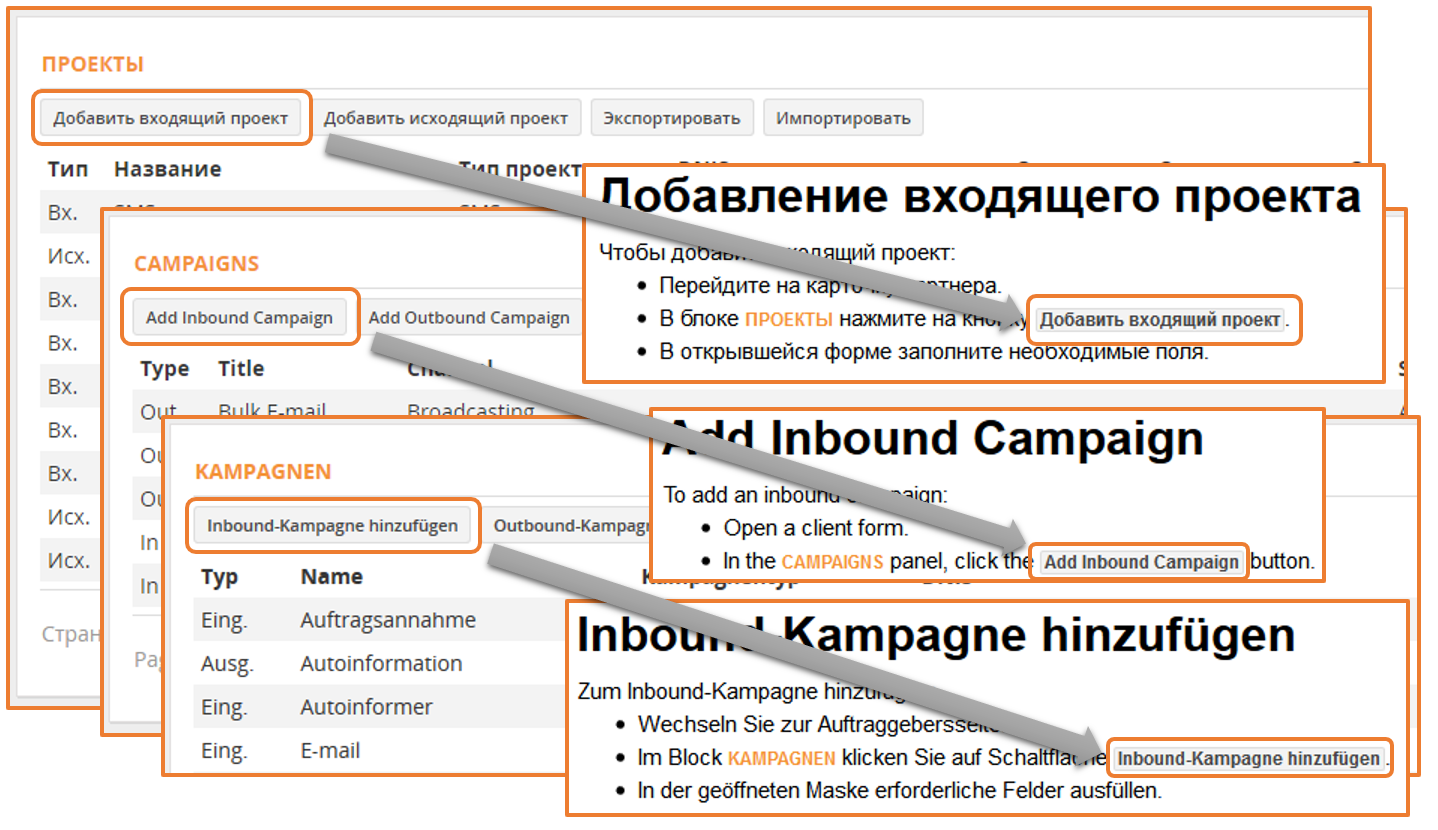

In most single-source systems, variables can be used. Therefore, we developed scripts that automatically convert interface resource files to variable files. In the process of developing documentation, we do not type texts of interface elements, but insert variables into the text. Thus, in the Russian version, Russian lines are automatically pulled in, in the English version, English, in German German.

What are the benefits:

- Errors in the text of interface elements are excluded if they are mentioned in the documentation. The texts of the interface elements in the documentation are always identical to the texts in the interface.

- If lines of text have changed in the interface, they automatically change in the documentation.

- Errors are excluded when translating texts of interface elements in the documentation.

- A translator spends less time working.

There are many duplicate sentences in the documentation. For example, a sentence such as - “Click on the Save button.”. In single source systems, such a proposal can be placed in a snippet. A snippet is such a small file that can be inserted into other pages of the documentation.

As you can see, the text of the Save button in the snippet is also substituted from the variable.

This provides the following benefits:

- Sentences identical in meaning are everywhere identical, which means that the uniformity of the text increases.

- The cost of developing documentation through reuse is reduced.

- Such sentences are translated only 1 time. This reduces the cost of the translator.

Screenshots and other images

In our documentation, we often use screenshots and other images that may contain text.

To take screenshots in different languages on our own, under each screenshot we write the text that is used on it. This text is tagged and does not appear in the finished documentation. Before we translate documentation, we translate texts for screenshots. And during the translation of the documentation we take screenshots by technical writers without knowledge of the language.

Using screenshots, there are other difficulties. For example, how to track all changes if the interface changes one line of text, which is used in 50 places?

How then to find all screenshots of these 50 places to replace them in the documentation?

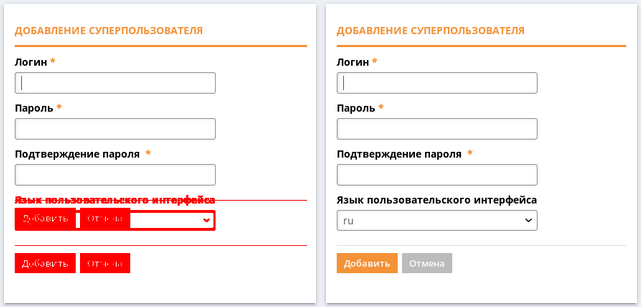

To solve this problem, we use the QVisual tool that we developed at Tinkoff. The process of working with it looks like this:

- During the development of documentation, under each screenshot we make a link to the stand where this screenshot is taken.

- At a certain point, we prepare a list of all the links.

- We load the received list into QVisual.

- QVisual runs through one version of the product and takes a set of screenshots.

- Next, we take the new version of the product and QVisual runs through it using the same links.

- QVisual then compares 2 sets of screenshots and generates a report. In the report, graphically, you can see the differences between the two versions. An example is below. You can immediately see that in the new version of the screenshot an additional field User interface language has appeared.

- Next, we repeat the comparison procedure (p. 1-6) for each language.

- We take the reports and go through the screenshots in the documentation.

In this way, we reduce the cost of numerous manual screenshot checks. Moreover, manually it is not always possible to identify all errors, you can simply overlook something.

True, not all windows can be opened using links and this only works for the Web interface, but it still removes some of the problems with updating screenshots.

Interface localization

Before localizing the interface, if this is not already done, you need to translate all the glossary terms.

When the glossary is translated, localization can begin. In this process, we adhere to the following principles:

- Use the glossary.

- We use the translation memory.

- We use the style guide.

- We use a context.

- We use automatic quality assurance (QA).

I note that the context may have a higher priority for deciding on a translation than having the same, already translated line in the translation memory. Also, based on the context, certain translation rules that are specified in the style guide may apply.

There can be several ways to provide context:

- As I wrote above, the context can be laid down in the string identifier itself or in additional fields of resource files (if the format allows).

- Screenshots may be added. At the moment, we are able to manually add screenshots to particularly complex lines.

- Providing stands and documentation in the source language. As practice shows, this method does not work. Translators usually do not use the materials and stands provided to them. Perhaps because the time it takes to translate one line increases many times.

Translation of documentation

The principles that we try to adhere to when translating documentation:

- First, we translate texts for screenshots and other images. As I wrote above, screenshots are taken in parallel with the translation of the documentation. This is done at the stand using the translated texts for screenshots.

- We translate only changed and new lines. Previously translated lines with a 100% match just do not look. Yes, you can re-read all documentation every release, but taking into account that each release is updated approximately 10% of the text, subtracting the remaining 90% of the text is an unjustified cost.

- Use the glossary. The glossary must be translated earlier, at the stage of localization of the interface.

- We use the memory translation documentation.

- We use the memory translation interface.

- We use the style guide.

- We use automatic quality control (QA).

Organizational structure and feedback

I will say a few words about the organizational structure of the company. It is different for everyone, but imagine a case where each department has its own department.

Feedback from one department to the previous in this version will be difficult, the interaction between employees of different departments is difficult. The solution of all issues through the head is also a "narrow neck". Each leader has his own vision, goals and priorities. A lot of time can be spent on additional approvals.

In my opinion, one department should be responsible for all texts in all languages.

With this distribution of responsibility, each version of the product is a separate project from several stages, and the quality of the implementation of this project must be answered as a whole. It’s easier to establish feedback, quickly understand any problem, make a retrospective and find the root cause of the problem.

I will give an example.

Due to the fact that our technical writers themselves verify translations using QA, we have seen dozens, if not hundreds, of inconsistency errors.

It turned out that the translator sees the sentences that are identical in meaning, but in different ways, and makes the same translation for them. We initiated the task and the technical writer replaced all different versions of the same text within the meaning of one snippet. Now there will be no such repeated errors. Specialists will not have to waste time analyzing them, and translating into new languages will be easier in the future.

In the general case, if the translator has questions during the translation, then for us this is a “bell” that something is wrong in the early stages and we need to do the correction task.

What quality documentation is needed

Before you try to make perfect documentation in all languages, it is worth considering what quality is needed? Additional questions will help to answer this question:

- Who are the users of the documentation?

If the documentation is in the public domain and the customers on the basis of it make the decision to purchase the product, then the quality should be close to ideal. If the documentation most often begins to be used after the implementation of the system and is read mainly by engineers (this is exactly the case with us), the quality of the documentation will not affect the decision to purchase. The main thing is that the instructions help solve problems. In this regard, it is important that everything is correct precisely in the technical part: command formats, functions, examples, and so on. Engineers are unlikely to pay special attention to grammatical or stylistic errors. - What is the number of users?

If no one reads the documentation, then no one will tell about errors, no one will see them. All proofreading will be in vain. How appropriate is it in this case to invest in the quality of the documentation or to read the translations? It might be better to spend some of the resources first to attract users.

Document proofreading and user feedback

If you decide to read the documentation:

- Not all can be subtracted.

Build statistics on the use of documentation and submit for proofreading, for example, the top 50 pages that are read by hundreds and thousands of users. If some pages are read 1-2 times a year, then they can be neglected. - It is better to read the finished documentation.

Not all problems can be seen in the CAT system. For example, matching pictures with text or matching different parts of the text in a common document (snippets, variables), a unified approach to the translation of headings, and the like. - No one except users who really solve problems with the help of documentation will say whether your documentation is of high quality or not.

- No one except a native speaker will say how well the documentation is translated.

We make web documentation with features already described available for internal use before the release. Proofreading documentation in Russian is done by the entire department, and especially by analysts, since they are the ones who set the tasks for development and at this stage they understand best what should be in the documentation.

New employees are also very valuable documentation users. Beginners have a fresh look, and the goal is to deal with the system during the trial period.

The translated documentation can also be read by partners. You can conclude such agreements with them. The partner sends you all the comments, but at the same time he understands the system.

What makes users send feedback:

- Everyone loves to criticize.

And so that the criticism does not remain somewhere in the smoking room, you can make a simple way to get it to us. We made a very simple form. You can select the text with the error, press Ctrl + Enter and click the Submit button. Sometimes writing comments is not even necessary. This takes very little time and does not cause much difficulty. - Comments should be processed.

Leaving a comment, the user enters a copy of the task and sees when and in which version it closed. If comments are ignored, users will quickly realize that they are wasting time and will not write more. - Users do this for themselves.

That is, they help to improve the documentation for themselves and for other users, receive satisfaction from this. The next time they need information again (in which there was an error or which was missing), they will find it in the documentation and they will not have to write the answer to the client themselves. They simply send the link to the customer who contacted technical support. In this way they reduce costs for themselves and their colleagues.

I note that we correct the comments only in the current version of the documentation, that is, the one that is still under development. We believe that it is better to pay as much attention to new versions as possible and make as few mistakes as possible than spend a lot of time supporting older versions.

conclusions

Each company is at its stage of development, and often it is not necessary to invest a huge number of human resources in order to achieve an acceptable result today.

First, figure out what exactly is needed at the moment and do just that, and increase costs as your needs increase.

This was a fairly general article about the processes of documentation and localization in general. In the future I will try to write about narrower topics.

Thank you if you read to the end! I wish you success in working and debugging your documentation and localization processes!

I will be glad to answer questions, discuss your thoughts and ideas!