The final part on how the Jobs-to-be-Done concept changes the principles of creating and improving an IT product. The third part of the translation of the book "Intercom about Jobs-to-be-Done." Chapters seven through nine.

First part

The second part of

Chapter 7. Refusing Persons: A Job Story

Posted by: Paul Adams

At Intercom, we constantly rethink internal processes to create an outstanding product. Therefore, we ask ourselves the question: how to build the process of creating a product so that people consider it valuable and convenient, and also love it. We focused on research, for which we hired people with research experience. At the same time, each member of the product team personally communicates with customers: product managers, designers and, of course, researchers. We also hired a research director, and we did it a lot sooner than most other startups do. He became Sian Townsend, head of the Google Maps research team.

Obviously, you need to communicate with customers regularly in order to understand themselves and their needs. However, it is not at all obvious which tool is suitable for this. We constantly thought about the ideas from the first principles and rather early applied them to the process of communication with customers.

We were big fans of Jobs-to-be-Done, but everything we wrote was applied mainly to milkshakes and chocolate bars. There was only one small study regarding the use of Jobs-to-be-Done for software development. So we created our own process based on what we already knew.

For most of my career, I have used people and scripts to understand clients. These tools, popularized by Alan Cooper in the book “Mental Hospital in the Hands of Patients,” have become one of the most widely used by researchers and designers. Alan Cooper also wrote an incredible book, “About the Interface,” which I recommend to all designers joining our team. But I ask them to skip the section on persons.

Working at Googl, I created hundreds, if not thousands, of people for many projects. We carefully followed Cooper's method, but in the end I came to the conclusion about the limited value of persons. They usually help to empathize with employees who are far from communicating with users, but rarely lead to breakthrough ideas or a fresh look at the problem.

And we at Intercom never used people again.

The first time I questioned the value of persons when I switched from Google to Facebook. They have accumulated an incredible amount of information about how users actually interact with their product. And communication with data Scientists did not cease to teach new things.

One of the most amazing things I learned was the incredibly similar behavior of different people. Persons made me believe that people are very different from each other, that they really have different goals. But the similarities were disproportionately greater, despite various factors: race, age, gender, etc.

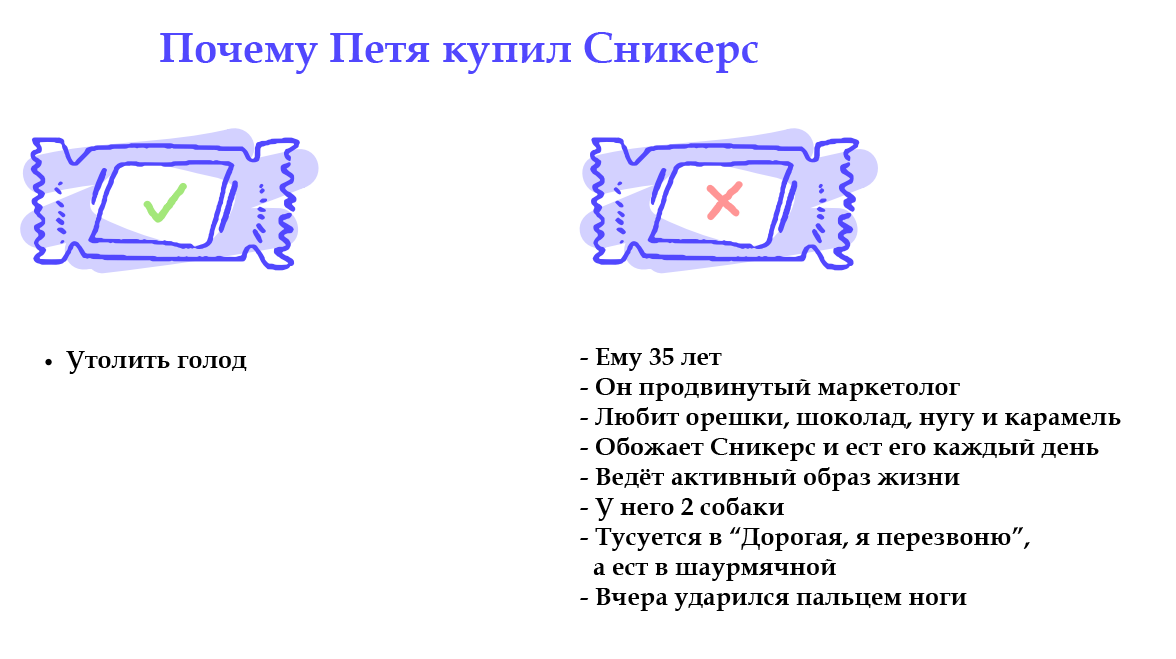

For example, the motives of a mother of three children from the United States, publishing photos from a family picnic, are basically the same as that of a Korean teenager posting pictures from yesterday’s appointment. The goals and details may be completely different, but the motivation is the same. Persons will never lead to the creation of the same product for completely different audiences. The best of their kind, people focus on achievements, “what drives people's behavior,” and on attributes. But in practice, most people focus only on attributes.

Persons artificially divide the audience. And, importantly, artificially limit the audience of your product by focusing on attributes, rather than on motivation and desired results. As soon as I realized this, I was disappointed in the person.

Designing from motivation is much better than designing from attributes. This is the key difference between persons from Jobs-to-be-Done. Persons - about roles and attributes, and Jobs-to-be-Done - about situations and motivation. Persons explain what kind of people they are, what they do and what they do, but they never fully explain why people do something, although this is much more important.

So in mid-2013 at Intercom, we realized that we were looking for a tool that would help uncover the reasons why customers do something. We spoke with many clients every week, and our customer support team talked even more often, creating development tickets taking into account the problems and limitations of our product. Such a direct relationship with customers cannot be overestimated, but there were two challenges that we had to overcome:

- People understand their problems, but not the solution. Moreover, it is more natural for them to propose a solution in the form of a request for the development of features. Describing the proposed solution is much easier than the problem. Because of this, you have to return to customers to ask questions and really understand their problem.

- In response, people initially talk about what they want in the language of attributes, but don’t give a reason why it is important to them. Therefore, you have to continue to dig deep into the understanding of their motivation. The main thing is to understand what kind of problem customers are actually trying to solve and why they need to be solved.

When the client’s problem is already clear, how to turn these insights into something tangible for the design team? Into something laconic that is easy to discuss and remember. I don’t remember the number of all cases during my work at Google, when we attracted colleagues to research and co-create people, so that later we would not use them. This is because people are hard to remember, they are too detailed to easily understand them. Persons are not concise enough for fast food teams.

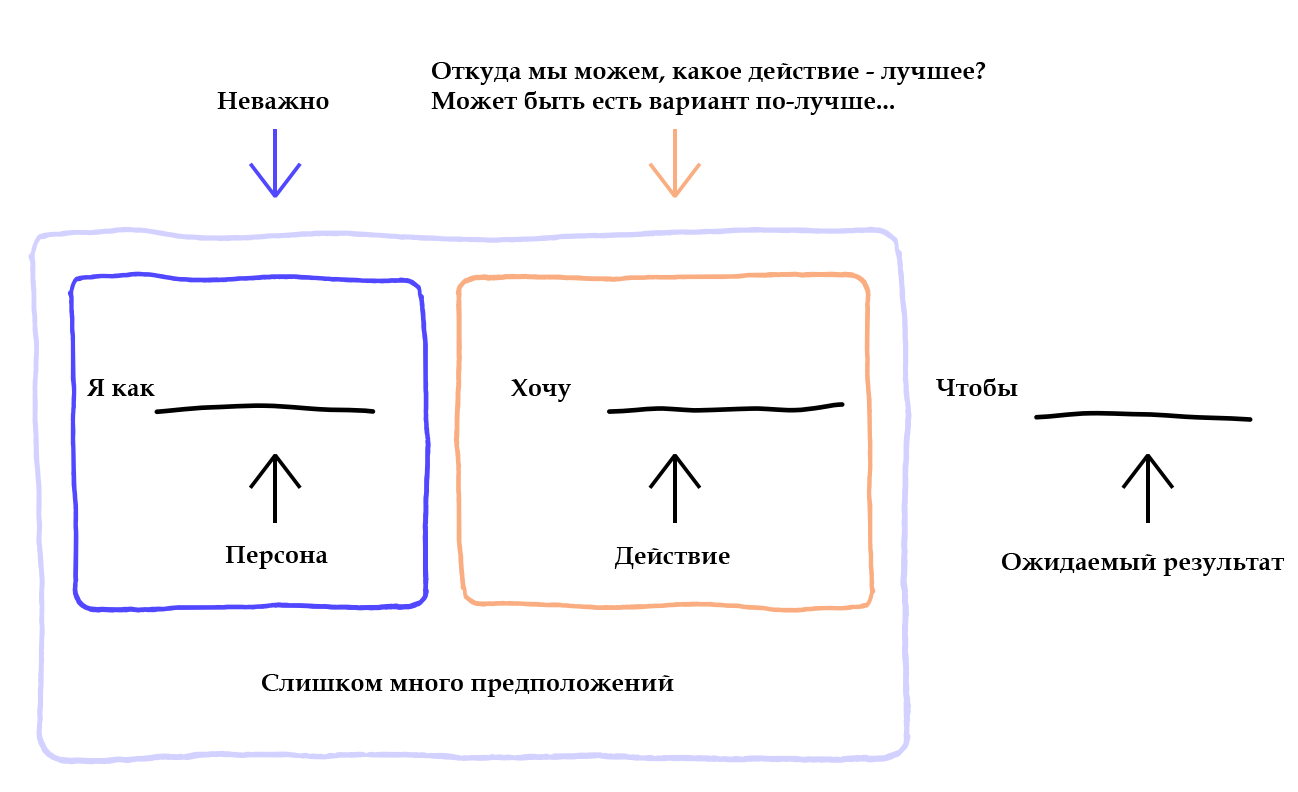

In addition to persons, there is another popular tool - User stories promoted by the Agile community. We never used User stories, because empirically they do not seem to be conditional on research. They are engineering, and certainly not caused by the client. They are designed to describe the functionality, not the motivation that people have.

After thinking about this problem and starting from the first principles, we invented Job stories. Then this artifact had no name. And later, Alan Klement came up with a name for us. But the process was ready and perfectly suited us. We tested Job stories for the first time, lamenting in a blog post about “ dribbling ” design. We thought long and hard about Jobs-to-be-Done, and this resulted in the creation of our own process, focused on situations, motivations and results:

[When ______] [I want ______] [I can ______]

“When ...” - about the situation, “I want ...” - about motivation, “I can ...” - about the result. If we understand the situation in which people encounter a problem, the motivation to solve it, and what the final result looks like, then we have the opportunity to make a valuable product for our customers.

Job stories are now our main tool, guaranteeing conditionality by research, comprehensibility of the problem and representation in a concise form. This means that our result of the study of the problem is suitable for both the design and engineering teams.

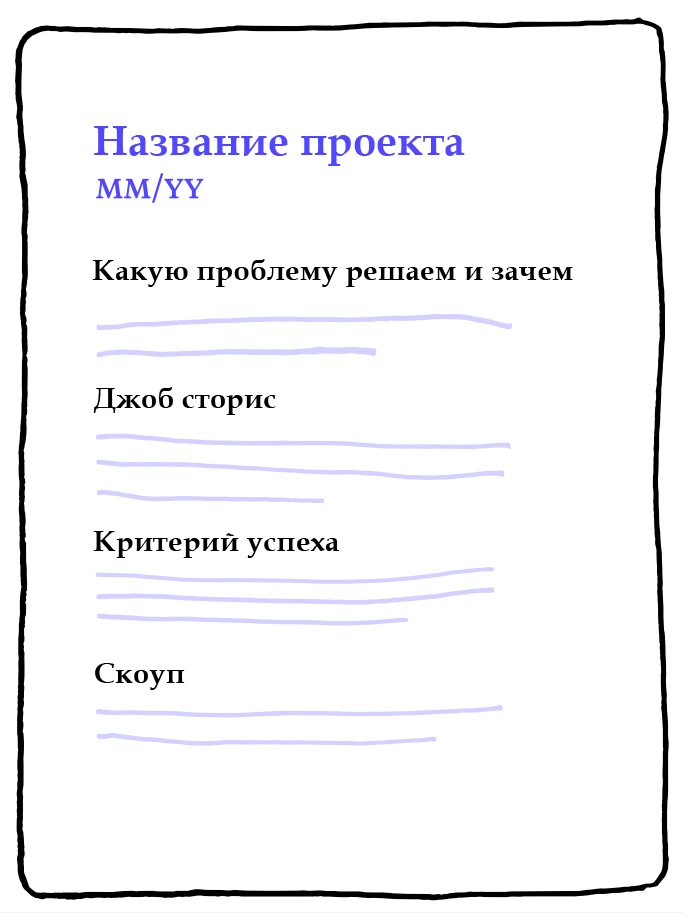

Before starting any project, we at Intercom create a very simple one-page brief that can be downloaded . It is very simple and should occupy 1 A4 page. It includes the Job stories section, which helps us not to forget about the problem and the opportunities we are tackling, and also gives us the opportunity to be focused throughout the project.

Persons definitely have a place to be. I find them useful for gaining support in the political game, when people only verbally solve the real needs of customers. Persons can also create stronger connections with current users of the product. But doing them well is a time-consuming process. Persons are fixated on differences between people and are difficult to remember and refer to. It turns out that many people with different attributes have very similar motivation. It is easy to understand, as well as the fact that everything that you are trying to gash can be explained in a series of short memorable sentences. If this does not convince you, then remember that people artificially reduce the market size of your product. That's why we drown for Job stories.

Chapter 8. Designing Features with Job Stories

Posted by: Alan Klement

When Des asked me to write for the Inside Intercom blog, I just presented Jobs-to-be-Done to my partners from Aim, an advertising marketplace for real estate.

Our design drawing process was mixed due to a lack of consensus. Each of us - I, as the general director, technical director and head of the design group - suggested what to design. Because we did not have an effective process of approving one idea and rejecting others.

And then it dawned on me. Without any reference to Jobs-to-be-Done, I began to pay attention to the most successful proposals made by the cofounders. I talked about what our customers are suffering with and described how much better their lives will be when we fix it. Then he showed how their proposals are good for a specific design task. As a result, I described the work that the client needs to do and the result when the work is done.

Using the Jobs-to-be-Done language for communications, we were able to validate our first design in just a few minutes. There was no turning back.

***

Persons and User stories have a place to be when customers and product teams are very far apart. But this is no longer a problem.

Traditionally, the answer to the questions “Who is our customer?” And “What do customers need?” Lies with marketing, a business department, or even a sales department. When the information is collected, it should be formed in a format that everyone understands, and then dropped into the product development team.

During this waterfall process, the nuances necessary to create good products are sacrificed: causes, anxieties and motivation. Jobs-to-be-Done is a philosophy of focusing on these nuances. To convey this concept to the final product, Job stories should be used during feature design, UI and UX.

Person failure

As Des said earlier, persons are usually defined through attributes that are not related to cause and effect relationships. For example, a person’s gender, age, race and weekend preferences do not explain why he loves Snickers. But the situation in which there is only 30 seconds to buy and eat something to satisfy the hunger for the next 30 minutes explains everything.

Failure User stories

"As a user, I can mark folders so that they are not backed up, so my backup disk will not be filled with what is not needed." This User story has three big problems:

- Used by person.

- Realization combines motivation and expectations.

- Ignored context, setting and fears.

Features often fail. If a feature was identified using a User story, it will not be easy to understand why it failed. This happens when motivation and expectations are combined in a decision. Because of this association, it is impossible to understand what exactly was wrong - the problem is in the implementation or in the assumption of motivation.

Introduction to Job Stories

Job stories, first mentioned by Paul Adams on Intercom's blog and developed here , are a completely different approach to feature development. But how do teams integrate them into their workflow?

Here is one approach:

- We start with high-level work.

- We define smaller works that help to perform high-level work.

- We are watching how people solve the problem now. This is the work they are doing.

- We use Job story to determine the cause-effect relationships, anxieties and motivation of what people are doing now.

- We create a solution that solves this Job story.

As an example, consider the process of designing a seller’s profile by a product team as part of a product that helps car dealers get a loan to customers.

Profile design

At the early stage of creating a design, the team discusses what the user profile should look like and what features it should be filled with. To begin with, Sarah, a member of the team, gets up and draws a simple layout on the board. Pointing to him, she says: "This is the seller’s profile."

The team is not impressed with her decision. A series of “why” questions are asked about each part of the layout. Even after all these questions, the team does not accept or reject this idea. These questions are: “Why does the product need this profile?”, “Why should the profile be here and not in another place?”, “What information should it show?”, “In what situations is it useful?”, “What kind of work does this profile?"

To answer these questions, the feature description was redesigned using the Job story.

Getting started with high-level work

The high-level work of the product is to help the car dealer get a loan to a prospective client. The client and the seller have to fill out a lot of complex papers.

We define smaller jobs that will help you perform high-level work.

To fill out a loan application without errors, the seller and the client are forced to enter a large amount of information about the car and about the loan conditions. Since the information is sensitive, the customer needs to feel that the data transfer to the seller is safe.

We are watching how people solve the problem now. This is the work they do.

When transmitting such information, buyers usually examine, as a rule, visually, the seller and the dealership, and conclude whether they deserve trust. Clients usually fill in sensitive financial information by sitting close to the seller. This helps them to feel confident that the information will be filled in correctly and at the same time will not be available to people who should not see it.

We use the Job story to determine the cause-effect relationships, anxieties and motivations of what people are doing now:

- When car dealers and their customers interact through a product ...

- ... customers want to trust the company, the process and the seller.

- Sellers want to be sure that the process is comfortable for the customer ...

- ... and he can safely enter his financial information.

It is written in Job story. You can specify by adding more situational context: when and where it is all filled, at home or in the dealership. As well as the fears of each of the parties associated with the profile and its completion.

Create a solution that fulfills this Job story

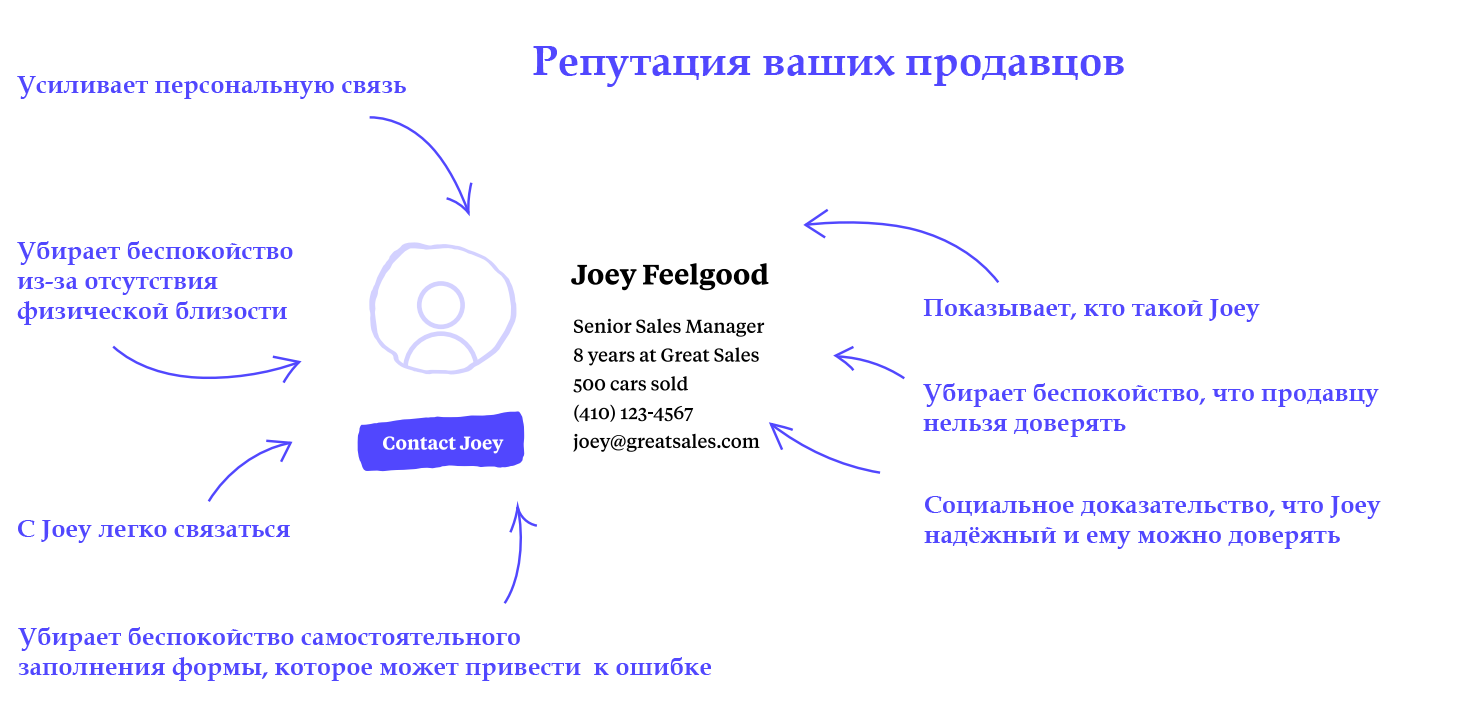

The team decides what design the profile should have in order for the client to complete his work. Displaying too little information in the profile will not solve the original work, and its large array can lead to negative consequences. As a result, the team decides:

- During use of the product, the seller’s profile will be constantly visible on the screen so that the buyer does not fear that he is not near the seller.

- The profile should contain a photograph of the seller, his position, the number of cars sold and the length of service in the company so that there is no doubt about the reliability of the seller and his experience.

- The profile should indicate how to contact the seller: phone number, e-mail and the “ask a question” button so that the client is not afraid that he might fill out the form incorrectly.

Here is an example solution:

The breakdown of the user interface is described below: the work that each element of the profile does and what situations it solves.

Now we have a product in which the roots of each solution to do the job can be found: to give a sense of security during the transfer of personal data by the client.

Sound design for people

Creating successful products means observing real people who are solving their problems, researching the context of the situation they are in, and understanding causation, fears and motivation.

Abstract attributes, the combination of realization with motivation and expectations drives teams crazy. If the team digs deeply and studies the work of the client, then it creates solutions more efficiently. Job stories are best suited for product design.

Chapter 9. Ask “why” - right

Posted by: Dan Ritzenthaler

Until I got into the Jobs-to-be-Done, I hardly defined the root problem so that it came down to a simple statement. How can I simply and clearly express it in front of team members? It is necessary to consider the problem from different angles for a better understanding of it. And asking “Why?” Is one of the best ways to delve deeper into what customers are trying to do.

There are many abstract tips and studies on how to discover cause and effect relationships. For example, the Five Why technique. In this chapter, we’ll talk about striving for a middle ground, about how to move inland through conversation levels, but not too fast so as not to lose valuable insights. The main thing is to find unique insights on each “why” level before moving on.

***

I cannot stop asking the question “why?” To each of your statements, and then ... I will again ask “why?”. This is a professional deformation.

Here, for example, you bought an electric drill. Why? Yes, because you want to hang a couple of photos in a frame. Why do you want to hang pictures? Probably to make your home more populated. Why is this important to you?

As for product design, the root cause is often too fast. But the value of asking “why?” Questions usually does not lie in reaching the destination, but in the movement towards it.

This is especially true for interviews with clients. Take your time and devote time to each “why?” Level, testing many different ideas. Then the time spent with the client will become more productive - the received insights will be much more interesting and useful.

Productive Talk Levels

You can always dig as deep as you want. The number of levels depends on the available time for a conversation, and the depth of each depends on the needs. This is a deeper understanding of the question “why?”.

Exploring the value of a product reveals many useful levels for discussion. The levels that I consider most valuable for research are as follows:

- First, the level of benefit: what do you directly do with the thing? I use a drill to drill holes.

- Secondly, the level of convenience: what result do you get? I made holes to hang pictures.

- Thirdly, the level of desires: what changed when I completed my work? I hung photos and now I have a more lived-in house.

What is said outside these three levels is difficult to attribute to the product. For example, asking, “Why do you want a more lived-in house?”, You are unlikely to get answers that are important for drill manufacturers.

But in any case, you will learn more about the person, as well as about what motivates her - it is always useful. But for me it is too specific, and rarely when it can be applied immediately.

Benefit level

In the electric drill example, the primary answer is the person’s need to make holes. You can go deeper and learn how to make a drill more useful.

Where should holes be drilled? In concrete? In a tree? In the metal? What size should they be: should they be narrow holes for small cogs or wide holes for large bolts?

How can this change the properties of the drill? Other power, torque, speed? Maybe a choice of speeds? Or different sizes of drill? And perhaps the presence of removable drills?

These are all great questions to figure out what the drill really needs to do and how to make it more useful. Unfortunately, it is impossible to understand how to make a drill easier to use.

Convenience level

The next level of use of a drill is to help hang photos in frames. If the result of using the drill is a wall-mounted photograph, then you can go deeper and learn how to make the drill more convenient.

What does a person do when he hangs pictures within? Is it comfortable for people to use a drill? Do they stand on chairs or other inappropriate household utensils when they are drilling? Are they worried that they can do something wrong? If we were developing a drill that only drills holes for photo frames, what would it be better?

How would this change the properties of the drill? Maybe small batteries would be needed, since it is not often used? Or maybe you need a smaller motor and body to reduce weight? Should there be more home wall presets to reduce anxiety?

These questions reveal the capabilities of the drill and ways to make it more convenient. But, unfortunately, they do not disclose methods to make a drill more attractive.

Desire level

The next level of drill use is to make your home more comfortable. If the result of using the drill becomes a more lived-in house, you can go deeper and learn how to make the drill more attractive.

How important is it to be ready to use when you come home with a new picture in a frame? Where do you put the drill when you finish the job? Is it in full view of everyone?

How does this change the properties of a drill? Does a docking station need to be easy to clean? Or should she hang on the wall to be always ready? Should the drill have an attractive appearance when lying on a table or on a shelf?

These questions will help create the feeling that the drill is designed specifically for you. You can imagine how it suits you and meets all the needs for creating comfort.

Do not hurry

When you ask about the work that a specific tool can do for a person, try not to rush to move on to an in-depth answer. Gold is usually not here. There is also no single final answer. Even if he is truly alone, this does not mean that this is the only value. Examine each level carefully for the unique value that it holds.

Conclusion

Initially, we at Intercom made a big bet on Jobs-to-be-Done as a means of informing about our product strategy. And later they used it to enter the market. Five years later, this concept is still at the core of our product and marketing strategy. We built the whole company around the idea that people are faced with problems in life or work, and to solve them, they buy products.

I do not know any direction of our business that would not change Jobs-to-be-Done. Product, marketing, sales and support have benefited greatly from focusing on this concept. Initially, we made decisions based on intuition about the various reasons why people should buy Intercom, but after about a year we conducted an exhaustive study on the work of our customers.

This research is as easy as talking to a client who has successfully completed an onboarding of your product. If you're interested in how you can reach out to specific users, Intercom will help you. When you decide to collect feedback, do not forget to focus your company on solving real customer needs.

Our unity with Jobs-to-be-Done is still evolving. This book is the beginning, a collection of our best reflections on theory at the moment. With the growth of our company and the expansion of customer needs, thinking also develops. For five years we would like to write several books that will contain advice and opinions.

If you have similar experience using the strategies from the book, I would be happy to know about it. Email me at des@intercom.com

Thanks for reading.