Security Week 39: security and commonplace errors

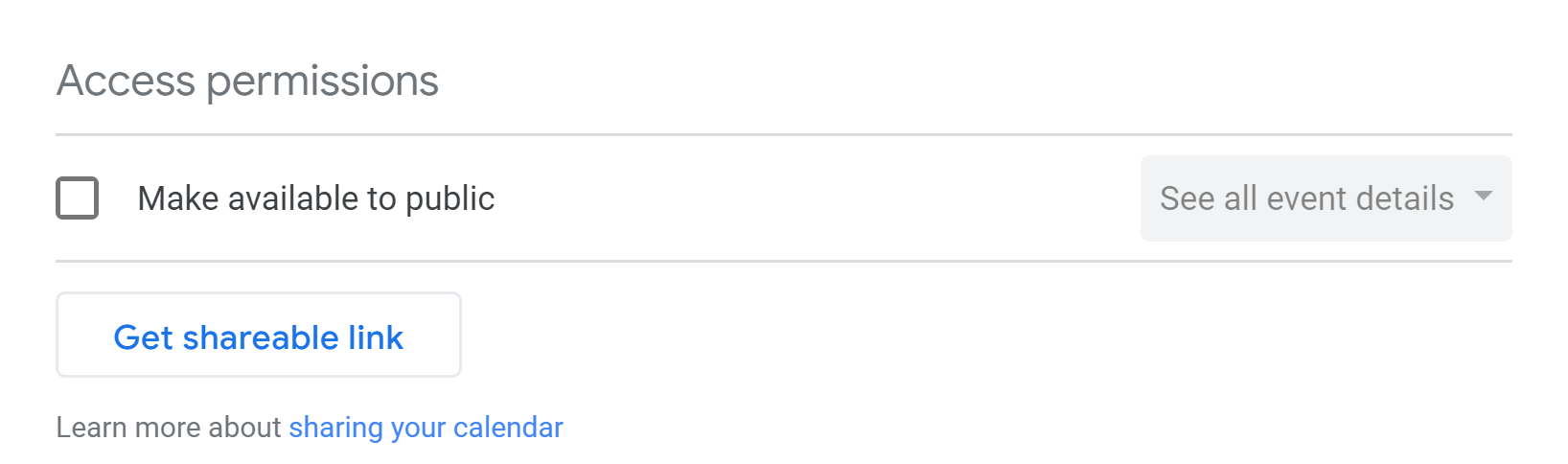

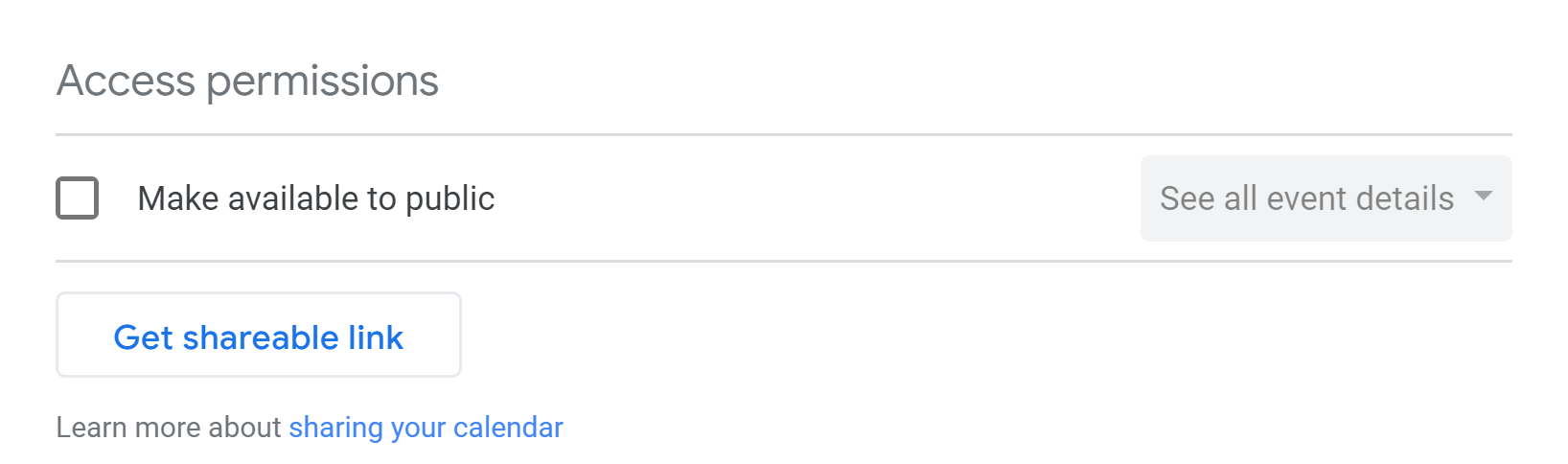

Last week, security specialist Avinash Jain discovered ( news , the original blog post ) hundreds of user calendars in the Google Calendar service in the public domain. Such calendars are indexed by search services, and in Google itself are available by a simple request like inurl: https: //calendar.google.com/calendar? Cid = .

Information about meetings, conference calls and important negotiations turned out to be public due to an elementary error in the calendar settings: instead of sharing data with specific users, they made the calendar accessible to everyone. Google commented on the story, saying that they had nothing to do with it, and user actions are voluntary. However, after a week, most of the search results still disappeared.

This is not the first time when discussing such problems, attempts have been made to find the extreme: either the developers of the interface mislead users, or the users themselves do not know what they are doing. And the point is not at all who is to blame, but the fact that even simple errors in data protection need to be fixed. Although they are not as interesting as complex vulnerabilities. Over the past week, several examples of elementary miscalculations have accumulated at once: in the LastPass password manager, in the iPhone lockscreen (again!), And also in the Google Chrome extension store, which allows the appearance of malicious ad blockers.

Let's start with Lockscreen in iPhones. Researcher Jose Rodriguez discovered ( news ) a hole in the iOS 13 device lock system back in the summer, when the latest version of Apple’s mobile OS was beta tested. Then he reported a problem at Apple, but iOS 13 went into production last week without a patch. The vulnerability allows you to see only the contacts on the phone and requires physical access to the device. The process of bypassing the lock screen is shown in the video. In short, you need to call the phone, select the option to answer the call with a message, turn on the VoiceOver function, turn off the VoiceOver function, after which it will be possible to add another recipient to the message. And then you get a complete list of contacts on someone else's phone.

In the entire history of iOS, there have been many such errors. The same Rodriguez discovered at least three similar problems in iOS 12.1 (transfer the incoming call to video mode, after which you can add other participants, which gives access to the address book), 12 (the same VoiceOver gives access to photos on the phone) and 9.0-9.1 (full access to the phone through commands to the Siri voice assistant). According to the researcher, the new problem will be closed in iOS 13.1, which will be released at the end of the month.

A slightly more complicated problem was discovered and closed in the LastPass password manager ( news , bugreport ). Researcher from the Google Project Zero team, Tavis Ormandy, found a way to steal the last username and password entered in the browser. The problem is simple, but its operation is quite complicated: you need not only to lure the user to the prepared web page, but also to force him to click several times so that the password is automatically entered into the attacker's form. In a non-standard (but used) script for opening a page in a new window, the LastPass extension for the browser did not check the page URL and substitute the last used data. On September 13, the vulnerability was closed .

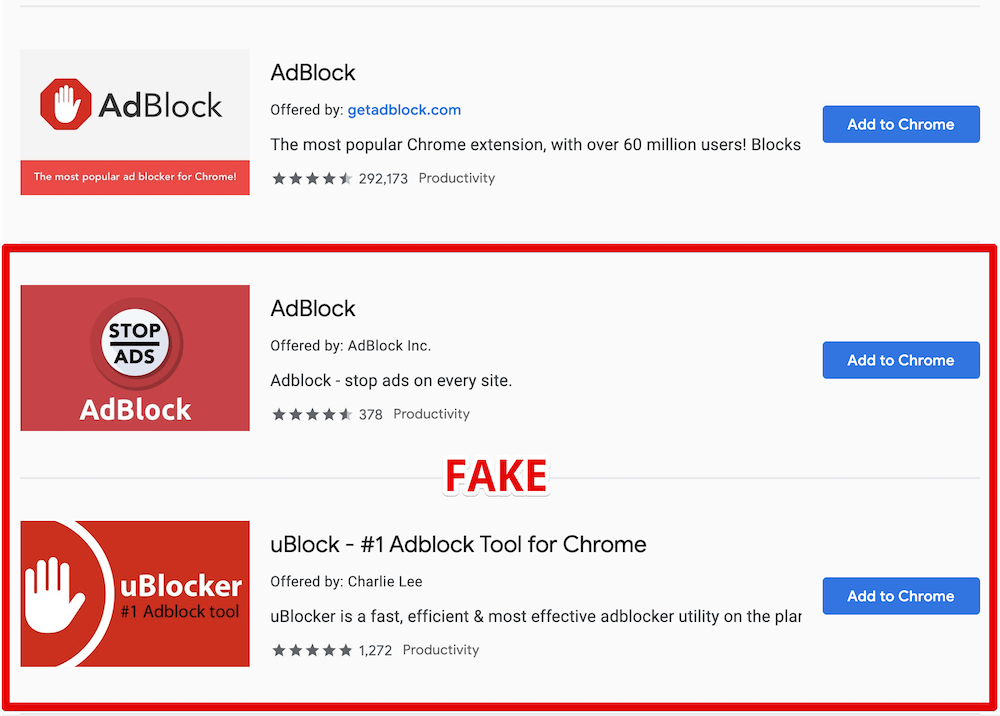

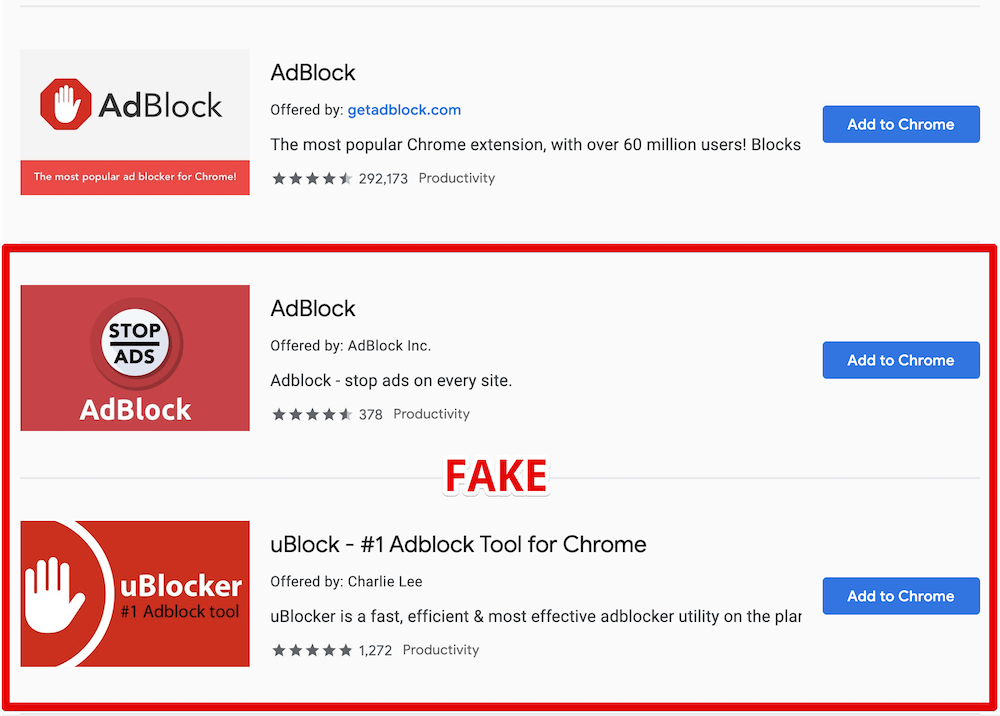

The LastPass newsletter provides a useful tip: installing a security system is no reason to relax. In particular, you can make a mistake by installing the wrong browser extension in the Chrome browser. On September 18, Google removed two plugins from the Chrome Extensions catalog that mimic the official Adblock Plus and uBlock Origin ad blockers. Fake blockers are described in detail on the AdGuard blog.

Fake extensions fully copy the functionality of the originals, but add the cookie stuffing technique. The user who installed this extension was identified for a number of online stores as having come via a referral link. If a purchase was made in the store, the commission for the “customer drive” was sent to the authors of the extension. Fake blockers also made attempts to hide malicious activity: advertising began only 55 hours after the extension was installed and stopped when the developer console was opened. Both extensions were removed from the Google Chrome catalog, but more than one and a half million users have used them before. The same AdGuard company last year announced five fake extensions with the ability to track the user, in total, installed more than 10 million times.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend treating any opinions with healthy skepticism.

Information about meetings, conference calls and important negotiations turned out to be public due to an elementary error in the calendar settings: instead of sharing data with specific users, they made the calendar accessible to everyone. Google commented on the story, saying that they had nothing to do with it, and user actions are voluntary. However, after a week, most of the search results still disappeared.

This is not the first time when discussing such problems, attempts have been made to find the extreme: either the developers of the interface mislead users, or the users themselves do not know what they are doing. And the point is not at all who is to blame, but the fact that even simple errors in data protection need to be fixed. Although they are not as interesting as complex vulnerabilities. Over the past week, several examples of elementary miscalculations have accumulated at once: in the LastPass password manager, in the iPhone lockscreen (again!), And also in the Google Chrome extension store, which allows the appearance of malicious ad blockers.

Let's start with Lockscreen in iPhones. Researcher Jose Rodriguez discovered ( news ) a hole in the iOS 13 device lock system back in the summer, when the latest version of Apple’s mobile OS was beta tested. Then he reported a problem at Apple, but iOS 13 went into production last week without a patch. The vulnerability allows you to see only the contacts on the phone and requires physical access to the device. The process of bypassing the lock screen is shown in the video. In short, you need to call the phone, select the option to answer the call with a message, turn on the VoiceOver function, turn off the VoiceOver function, after which it will be possible to add another recipient to the message. And then you get a complete list of contacts on someone else's phone.

In the entire history of iOS, there have been many such errors. The same Rodriguez discovered at least three similar problems in iOS 12.1 (transfer the incoming call to video mode, after which you can add other participants, which gives access to the address book), 12 (the same VoiceOver gives access to photos on the phone) and 9.0-9.1 (full access to the phone through commands to the Siri voice assistant). According to the researcher, the new problem will be closed in iOS 13.1, which will be released at the end of the month.

A slightly more complicated problem was discovered and closed in the LastPass password manager ( news , bugreport ). Researcher from the Google Project Zero team, Tavis Ormandy, found a way to steal the last username and password entered in the browser. The problem is simple, but its operation is quite complicated: you need not only to lure the user to the prepared web page, but also to force him to click several times so that the password is automatically entered into the attacker's form. In a non-standard (but used) script for opening a page in a new window, the LastPass extension for the browser did not check the page URL and substitute the last used data. On September 13, the vulnerability was closed .

The LastPass newsletter provides a useful tip: installing a security system is no reason to relax. In particular, you can make a mistake by installing the wrong browser extension in the Chrome browser. On September 18, Google removed two plugins from the Chrome Extensions catalog that mimic the official Adblock Plus and uBlock Origin ad blockers. Fake blockers are described in detail on the AdGuard blog.

Fake extensions fully copy the functionality of the originals, but add the cookie stuffing technique. The user who installed this extension was identified for a number of online stores as having come via a referral link. If a purchase was made in the store, the commission for the “customer drive” was sent to the authors of the extension. Fake blockers also made attempts to hide malicious activity: advertising began only 55 hours after the extension was installed and stopped when the developer console was opened. Both extensions were removed from the Google Chrome catalog, but more than one and a half million users have used them before. The same AdGuard company last year announced five fake extensions with the ability to track the user, in total, installed more than 10 million times.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend treating any opinions with healthy skepticism.

All Articles