DeepMind's epic mission to solve the most complex science problem

DeepMind AI beat Chess Grandmasters and Go Champions. However, now the founder and director of the company, Demis Hassabis, has set his sights on larger real-world problems that can change our lives. The first one is protein folding.

Demis Hassabis - a former child prodigy, a Cambridge diploma with outstanding services in two subjects at once, a five-time champion of world intellectual games , a graduate of MIT and Harvard, a game developer, an entrepreneur from adolescence, a co-founder of a DeepMind startup developing artificial intelligence - is in a yellow helmet, reflective vest and work boots. He raises his hand, blocking his eyes from the sun, and looks across London from the roof of the building at Kings Cross. In any direction of the world, the view from there on the capital, bathed in the spring sun, practically does not obscure anything. Hassabis crosses the paved roof, and, using the phone to determine the direction, looks north to see if he can see the city of Finchley from where he grew up. The suburb is lost behind the trees of Hampstead Heath, but he manages to examine the slope leading to Highgate, where he lives with his family today.

Here he studies the location of the future headquarters of DeepMind, a startup he founded in 2010 with Shane Legge, a researcher at University College London, as well as his childhood friend Mustafa Suleiman. Now this building is a construction site on which hammers, drills and jack hammers are constantly rattling. Today 180 contractors are working at the construction site, and at the peak of construction their number will increase to 500. This place, which is scheduled to open in mid-2020, represents, figuratively and literally, a new beginning of the company.

“Our first office was in Russell Square, it was a small office for ten people on the top floor of a townhouse next to the London mathematical community,” recalls Hassabis, “in which Turing delivered his famous lectures.” Alan Turing, a British computer pioneer, is a sacred figure for Hassabis. “We build on the shoulders of giants,” says Hassabis, referring to other key figures in science, “Leonardo da Vinci, John von Neumann,” who also made significant breakthroughs.

The location of the new headquarters - north of Kings Cross Station, in a place recently called the Nolige Quarter - is characteristic in itself. DeepMind was founded when most of London's startups obeyed the pull of Old Street. But Hassabis and his founding colleagues had other plans: to "solve the problem of intelligence" and to develop a general-purpose AI (IION), applicable to various tasks. So far, this problem has been solved through the creation of algorithms that can win in games - Breakout, chess and go. The next steps are to apply this scheme to scientific research in order to break into complex problems in chemistry, physics and biology with the help of computer science.

“Our company focuses on research,” says Hassabis, who is 43 years old. “We wanted to sit next to the university,” by which he refers to University College London (UKL), in which he was given a doctorate for his work “Neural processes at the heart of episodic memories.” “Therefore, we like to be here, we are still not far from the UKL, the British library, the Turing Institute, not far from the imperial college ...”

Going down several floors, Hassabis is studying one of the territories that interests him the most - there will be an audience for lectures. He is pleased to consider the drawings and computer renderings of how this room will look.

On the northeastern corner of the building, his gaze rises into a large free space spanning three floors, where the library will be located. In this place, eventually an object will appear that Hassabis seems most eager to see the most: a huge staircase in the form of a double spiral, which is now being assembled in parts. “I wanted to remind people of science and make it part of this building,” he says.

Hassabis and his associates know that DeepMind became famous for its breakthroughs in machine learning and deep learning, as a result of which the press widely covered cases where the neural networks that worked with algorithms perfectly mastered computer games, beat chess grandmasters, and forced Lee Sedol, world champion in go - which is considered the most difficult game of those invented by man - to declare: "From the very beginning of the game there was not a single moment when I thought that I could win."

In the past, machines that played games with people showed characteristics that were clearly inherent in the algorithms - their style of play was tough and unyielding. But in the go competition, the DeepMind AlphaGo algorithm beat Sedol the way a human could. One strange move - the 37th in the second installment - made the audience who watched the game live in Seoul gasp and amazed millions of online viewers. The algorithm played with such freedom, which may seem to a person a sign of creativity.

Hassabis, Suleiman and Legge believe that the first nine years of DeepMind's existence were determined by the need to prove the value of research in the field of training with confirmation - the ideas of systems with agents that not only try to model the world and recognize patterns (like deep learning), but also actively make decisions and trying to achieve your goals. At the same time, the next ten years will determine achievements in the field of games: namely, data and machine learning will be used to solve the most complex problems of science. According to Hassabis, the company's next steps will be attempts to understand how deep learning will help scale reinforced learning to solve real-world problems.

“The problem with reinforcement learning was that it was always used to solve toy problems and small lattice worlds,” he says. “It was believed that it could not be expanded to the wrong, real problems - and here a combination of methods comes into play.”

For DeepMind, the emergence of a new headquarters is a symbol of a new chapter in the company's history, just as it throws all its strength and computer power into an attempt to understand, among other things, how the building blocks of organic life work. By this, the company hopes to make breakthroughs in medicine and other disciplines, which will seriously affect progress in various fields of science. “Our mission should be one of the most interesting travels in all of science,” says Hassabis. “We are trying to build a temple of scientific aspirations.”

From left to right: Pravin Shrinivasan, head of DeepMind at Google; Drew Pervez, Creative Director of Worlds; Raya Hadsel, Researcher. Inside the unfinished headquarters of DeepMind.

Studying at University College London and then at MIT, Hassabis found that interdisciplinary collaboration was a very fashionable topic. He recalls how working conferences were held with the participation of representatives of various disciplines - for example, neurobiology, psychology, mathematics and philosophy. A couple of days there were reports and debates, then scientists returned to their departments, confident that they should meet more often and find ways to cooperate. And the next meeting took place a year later - applications for grants, appointments to teaching posts, and the routine of research and teaching life got in the way of cooperation.

“Interdisciplinary collaboration is difficult to organize,” says Hassabis. - Suppose we take two leading world experts in mathematics and genetics - they obviously can have common topics. But who will make efforts to sort out another person’s area, their jargon, what their real problem is? ”

Finding the right questions, the reasons for the lack of answers, and the main quotes, because of which these answers are not, this process may seem straightforward to an outside observer. But different scientists, even in the same field, do not always evaluate their work equally. Researchers find it extremely difficult to add value to other disciplines. It is even more difficult to find common questions that they can answer.

The current headquarters of DeepMind, the two floors of the Google Building at Kings Cross, has received more and more employees over the past couple of years. Only in the field of AI research, the company has six to seven different disciplines, and as part of the expansion of the range of classes, it hires specialists in mathematics, physics, neurobiology, physiology, biology and philosophy.

“Some of the most interesting areas of science are between classical areas, at the intersections of various research topics,” says Hassabi. - When creating DeepMind, I tried to find “unifying people”, world-class specialists in various fields, whose creative approach helps to look for analogies and common ground in various fields. In general, when this happens, then there is magic. ”

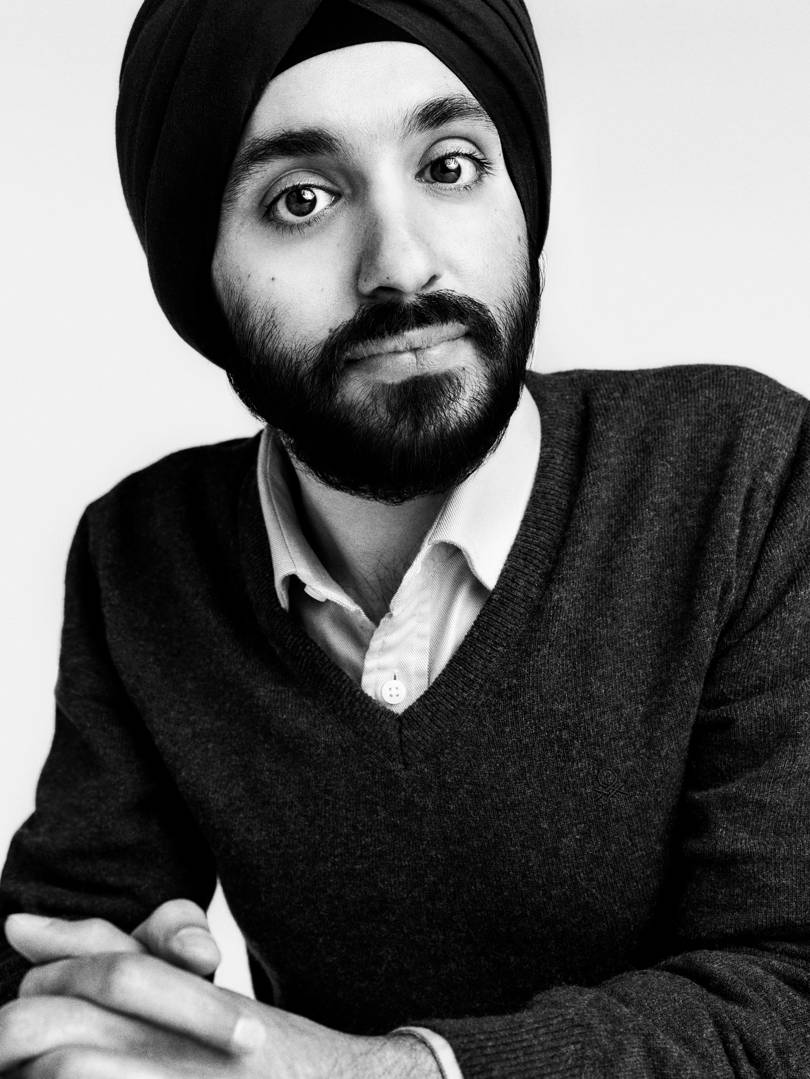

One of these unifying people is Pashmit Koli. Former Director of Microsoft Research leads the science team at DeepMind. There is a lot of talk in AI circles about the possible end of the “winter of AI” - a period without tangible progress - in the middle of the last decade. The same sense of movement applies to the task of folding proteins , the science of predicting the form of what biologists consider to be the building blocks of life.

Coley assembled a team of structural biologists, machine learning experts and physicists to attack this problem, recognized as one of the most important issues of science. Proteins underlie the life of all mammals - they make up a large part of the structure and functioning of tissues and organs at the molecular level. Each is composed of amino acids that make up the chain. Their sequence determines the form of the protein, which determines its function.

“Proteins are the most amazing machines ever created for moving atoms on a nanoscale, and often crank up chemistry a few orders of magnitude more efficient than anything we have done,” says John Jumper, a researcher in protein folding at DeepMind. "And they are also in some way inexplicable, these self-assembled machines."

Proteins use atoms on an angstrom scale [10 -10 m, or 100 pm / approx. trans.], [obsolete] units of length ten billion times less than a meter. A deeper understanding of this mechanism would enable scientists to better understand structural biology. For example, proteins are necessary for almost everything that happens inside the cell, and improper protein folding is considered an important factor in the occurrence of diseases such as Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease and diabetes.

“If we can figure out natural proteins, we can create our own,” says Jumper. “The question is to study this complex microscopic world very carefully.”

The widespread dissemination of genome data has made an attractive protein folding riddle for DeepMind. Since 2006, there has been a sharp increase in the receipt, storage, distribution and analysis of DNA data. Researchers estimate that by 2025 two billion genomes will be analyzed, which will require 40 exabytes of storage.

“From the point of view of deep learning, this is an interesting task, because after spending a huge amount of resources and time, people have collected such an amazing collection of proteins that we have already figured out,” said Jumper.

Progress is underway, but scientists are warning us of the huge diversity within this problem. Outstanding American molecular biologist Cyrus Levintal noted that it would take time beyond the age of the universe to sort through all the possible configurations of a typical protein in search of the correct three-dimensional structure. “The search space is huge,” says Rick Evans, a researcher at DeepMind. “More than in go.”

However, a milestone on the path to learning about protein folding was achieved in December 2018 at the CASP [Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction Techniques] competition in Cancun, Mexico. This competition is held every two years to provide an unbiased look at the progress in this area. The goal of the competing teams of scientists is to predict, based on amino acid sequences, the structure of proteins whose three-dimensional form has already become known, but has not yet been published. An independent commission evaluates the predictions.

The DeepMind protein folding team took part in the competition to test their new AlphaFold algorithm developed in the previous two years. In the months leading up to the competition, the organizers sent data sets to team members from King Cross, and they returned their predictions without knowing the final result. In general, they needed to predict the structure of ninety proteins - in some cases, the already known proteins were used to make predictions based on them, while others had to be thought out from scratch. Shortly before the conference, they received competition results: on average, AlphaFold predictions were more accurate than any other team. By some estimates, DeepMind is significantly ahead of the competition; for proteins whose structure was modeled from scratch - and there were 43 out of 90 - AlphaFold made the most accurate predictions for 25 proteins. This is surprisingly much compared to the runner-up team, which managed to correctly predict just three structures.

Ribbon diagram, a schematic three-dimensional representation of the structure of a protein folded into a three-dimensional structure according to the predictions of the AlphaFold algorithm for the CASP13 competition

Mohammed Al Quraishi, a researcher at the Systems Pharmacology Laboratory and Systems Biology Department at Harvard Medical School, was present at the competition and learned about the approach used in DeepMind, even before the results were published. “When reading the resume for the job, I did not think that this was something completely new,” he says. “I decided that they should do quite well, but I did not expect them to do so well.”

Al Quraishi says that this approach was similar to the approach of other laboratories, but the DeepMind process was distinguished by the fact that they could "perform better". He points to the engineering strengths of the DeepMind team.

“I think that they can work better than groups consisting of scientists, since the latter tend to keep their work a secret,” says al-Quraishi. “And although all the ideas that DeepMind included in their algorithm already existed, and different people tried to apply them separately, no one thought to bring them together.”

Al Quraishi draws parallels with the scientific community in the field of machine learning, from which in recent years there has been an outcome in companies such as Google Brain, DeepMind and Facebook; they have more efficient organizational structures, large rewards and computing resources that are not always found in universities.

“Machine learning communities have really experienced this in the last 4-5 years,” he says. “Computational biology is only now beginning to be mastered with this new reality.”

He is echoed by the explanation given by the founders of DeepMind regarding the sale of Google in January 2014. The volume of the Google computer network will allow the company to advance research much faster than if it had grown naturally, and a check of £ 400 million allowed the startup to hire world-class specialists. Hassabis describes a search strategy for people who are deemed suitable for specific research areas. “We have a development plan from which it follows which areas of research, from AI or neurobiology will be important,” he says. “And then we set off in search of and find the best person in the world who is also suitable for us in cultural terms.”

“So from those areas where DeepMind can change the world, protein folding seems to be a great start - this is a very well-defined task, it has useful data, it can, in principle, be considered as a task in computer science,” says Al Quraishi. - In other areas of biology, this approach probably will not work. Everything is much less orderly there. Therefore, I don’t think that the success of DeepMind in the field of protein folding can be automatically transferred to other areas of research. ”

DeepMind employees on the rooftop of Kings Cross's Google office

DeepMind is actively involved in product management for a research company. Every six months, senior managers study priorities, reorganize some projects, inspire teams - especially engineers - to move from one area to another. Disciplines mix constantly and intentionally. Many of the company's projects last longer than six months - usually from two to four years. But while DeepMind is focusing on research, the company is now a division of Alphabet, the parent company of Google, and the fourth most expensive in the world. And if London scientists are expecting long-term and advanced research from the company, directors from Mountain View in California naturally expect a return on investment.

“We make sure that our products bring success to Google and Alphabet, and they profit from our research - and they get it, now dozens of products containing code and DeepMind technologies are already working in Google and Alphabet - however, it is important that this situation is maintained not violently, but naturally, ”says Hassabis.DeepMind at Google, led by Suleiman, consists of hundreds of people, mostly engineers, who translate the company's purely scientific research into applications that can be turned into a product. For example, WaveNet, a generative text-to-speech model that simulates a human voice, is already included in most devices containing Google, from Android to Google Home, and has its own product team at Google.

“A lot of industry research is being driven by product requests,” says Hassabis. - The problem is that research can only go on an increasing basis, step by step. It’s unproductive to conduct ambitious and risky research - but this is the only way to make breakthroughs. ”

Hassabis speaks quickly, often emphasizing the end of the sentence with the question “yes?”, Leading the listener through a sequence of observations. He often distracts from the topic, periodically leaving for philosophy (his favorite philosophers - Kant and Spinoza), history, games, psychology, literature, chess, engineering, many other scientific and computer fields - but he does not lose his original train of thought, often returning to clarify the comment or discuss the previous comment.

Like the 300-year development plan for Masayoshi Sana, founder of SoftBank, a Japanese international bank that has invested in many dominant technology companies, Hassabis and the other founders have a “decades long development plan for DeepMind.” Legg, the company's leading scientist, kept a printout of the first business plan that they sent to a potential investor (Hassabis lost his copy). Legg sometimes shows it in general meetings to show that many of the approaches that the founders thought about in 2010 - training, deep learning, reinforced learning, simulations, concepts and transference learning, neurobiology, memory, imagination - are still key parts of the company's research program.

At the beginning of the journey, DeepMind had the only web page containing only the company logo. Neither the address, nor the phone, nor the positive page about us. To hire staff, the founders had to rely on the personal contacts of people who already knew that they were “serious people with serious scientists and a serious plan,” says Hassabis.

“At any startup, you have to ask people to trust your management,” he says. “But it’s even more difficult for us, because we, in fact, say that we will be engaged in work in a unique way, as no one has done before, and many traditional world-class scientists would say that this is impossible: 'Science cannot be organized in this way '".

How exactly scientific breakthroughs occur is no more known than how to solve some problems that researchers are struggling with. In the academic world, the best minds gather at institutes to conduct research that proceeds gradually, without predictable results. Progress is usually slow and time consuming. And in the private sector, where there are supposedly no restrictions, and there is access to highly paid consultants, productivity and innovation are also falling.

In February 2019, Stanford economist Nicholas Bloom published work proving a decline in productivity in a wide range of areas. “Researchers have grown significantly, and productivity has plummeted,” Bloom wrote. “A good example is Moore's law.” To maintain the famous doubling of the density of computer chips every two years, today 18 times more researchers are required than in the early 1970s. In the widest range of various studies at different levels of aggregation, we see that ideas - and especially the exponential growth embedded in them - are becoming increasingly difficult to find. ”

Hassabis mentions billions invested in Big Farm research: building on quarterly earnings reports, the industry has become more conservative as the cost of error has increased. According to a 2018 report from the Nesta Innovation Fund, over the past 50 years, the productivity of research and development in biomedicine has been steadily declining - despite a significant increase in investment, new drugs are becoming more expensive to develop. The report states that “the exponential increase in the cost of developing new drugs directly affects small returns on R&D spending. According to recent estimates, this return is 3.2% for the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world; it is much less than the cost of capital. ” Similarly, researchers from Deloitte estimated that return on investment in R &D biopharma is at its lowest level in nine years, falling from 10.1% in 2010 to 1.9% in 2018.

“Most directors of big farms are not scientists, but financiers or marketers,” says Hassabis. - What does this say about their organizations? They are trying to squeeze as much of the money already invested as possible, cut spending, improve advertising, but not invent something new - this is much riskier. You can’t write such a thing in a spreadsheet. This is not in the spirit of the work of imagination and dreams of the future - it is not necessary to act if you want to fly to the moon. ”

Pushmith Coley, Head of Research Team

Many startup founders in their mission have a piece of unexpected happy events - the problem they faced and set out to solve, an accidental meeting with a co-founder or investor, a supporter from the academic community. But this is not the case of Hassabis - he deliberately made several decisions, one after another - some of them at a very young age - which ultimately led him to create DeepMind. “This is what I’ve been preparing for all my life,” he says. - From game design to gaming, from neurobiology to programming, from studying AI at the institute to studying at many of the best institutes in the world, from a doctoral dissertation to organizing a startup in the early part of a career. I tried to use every crumb of experience. I deliberately chose all these milestones so as to get all this experience. "

Add to this the position of CEO, the work that he does every day. He has another role as a researcher, and in order to keep up with everything, he structures time, dividing it into separate periods, in order to balance business management and scientific interests. Having performed the role of director during the working day, he returns home at 19:40, has dinner with his young family, and then leaves for the “second day”, starting somewhere at 22:30 and ending at 4: 00-4: 30.

“I love this time,” he says. - I have always been an owl since childhood. There is silence in the city and in the house, and it helps me a lot to think, read, write. It is then that I will learn all the latest scientific news. Or I can write a work, edit it, come up with a new algorithm, some kind of strategy, explore the field of science to which AI could be applied. ”

During work, he listens to music. The style of music - from classical to drum and bass - depends on “those emotions that I try to awaken in myself. It depends on whether I want to concentrate or arouse the imagination. ” There are a couple of requirements to music: there should be no vocals, otherwise he is distracted by words; and the music should be familiar enough. “It should be something familiar, but not much. And it cannot be new music, it distracts the brain a lot. ”

Hassabis says he would like to spend 50% of his time doing direct research. To do this, in April 2018, he hired Laila Ibrahim, a Silicon Valley veteran who worked at Intel for 18 years before becoming HR Director at Kleiner, Caulfield, Perkins and Byers, one of the largest venture capital firms in the Valley, and then transferred to Startup Coursera. Ibrahim takes away many managerial tasks from Hassabis - he says that of the 20 people reporting directly to him, there are now 6 left. Ibrahim believes that she joined the DeepMind “moral considerations” that arose after talking with Hassabis and Legge regarding their Ethics initiative and society, ”which is trying to enforce technology application standards.

“I think working in London offers a slightly different perspective,” she says. - I think that if DeepMind's headquarters were located in Silicon Valley, everything would be completely different. London seems to have a lot more humanity. Art, cultural diversity. And they also have what the founders supported from the very beginning, and the people who decided to work at DeepMind brought a special way to the company to do things, a special attitude. ”

Layla Ibrahim

One case reveals what Ibrahim describes. Hassabis was a chess prodigy. From the age of four, he began to grow in rankings, until at the age of 11 he was at the major international championship, playing against the Danish grandmaster in a city hall near Liechtenstein.

After almost 12 hours, the game was drawing to a close. Hassabis had never seen such a deal before - he had a queen, and the opponent had a rook, elephant and horse, but Hassabis could still reduce the matter to a draw if he could constantly check the opponent. The hours passed, other games were already over, the room was empty. Suddenly, Hassabis realized that his king was trapped, which meant an inevitable mate. Hassabis surrendered.

“I'm very tired,” he says. “We have been sitting there for 12 hours or something, and I think that I must have been mistaken, and he trapped me.”

His opponent - Hassabis recalls that the man was 30-40 years old - stood up. His friends surrounded him, he laughed and pointed to the board. And then Hassabis realized that he had given up in vain - the game could be reduced to a draw.

“I just had to sacrifice the queen,” he says. - This was his last chance. For hours he tried to lure me. And that was his last cheap trick. And it worked. In fact, my 12 hours of exhausting work did not lead to anything. ”

Hassabis recalls that at that moment he received an insight. He wondered about the usefulness of such a pastime when brilliant people compete with each other to win in a zero-sum game. Then he continued to play at the highest level, became the team captain at the university, and still talks about his love for complex games, but experience taught him to redirect his energy to tasks that are not related to games. “I could not become a professional chess player, because it seemed to me unproductive,” he said.

Despite the fact that the company is moving to a new headquarters, Hassabis still considers DeepMind a startup, albeit competing on the world stage. “China has mobilized, like the United States. Serious companies do these things, ”he says. Indeed, the US and China are trying to standardize this area, and turn it to their advantage, both from a commercial and from a geopolitical point of view. He mentions several times that, despite progress, they still have a long way to go to a larger goal - solving the problem of intelligence and creating IION. “I want us to keep this thirst, the speed of work, the energy that the best startups have,” he says.

Innovations are rare; they are difficult to create. To build processes and culture in a company that will allow it to “leave a mark in the Universe,” as few organizations have managed to do so in several areas with several products, as Steve Jobs told the team that created the Macintosh computer. With the growth of DeepMind, founders will be required to guide it along the right path, following the fundamental principles of a business focused on technology that is likely to become the most transformative of all in the coming years, along a path full of not only dangers, but also opportunities.

“There will be many difficult days on the road, and I think that in the end, the desire to make money or something like that is not enough to go through the most difficult times,” says Hassabis. “If you have real passion and faith in the importance of what you are doing, then I can lead you through these days.”

All Articles