Lessons learned 40 years after take-off and rapid decline of the first “killer application”

Remember VisiCalc, the world's first spreadsheet? And today's technology giants remember - that’s why they buy and invest in potential competitors

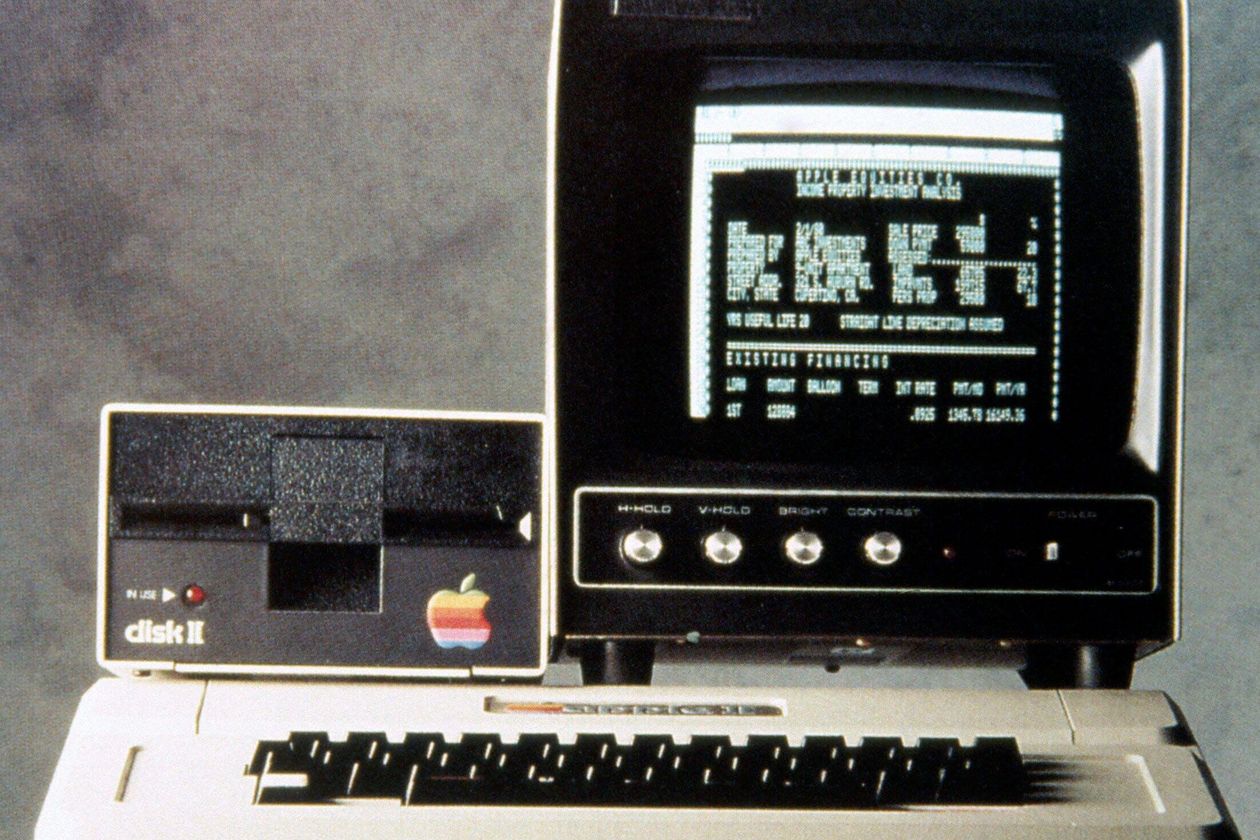

Initially, VisiCalc only worked on Apple II. It cost $ 100, and a computer - at least $ 2000.

It was the first killer app , a spark of Apple’s early success, and the trigger for the wider PC boom that raised Microsoft to its center of business computing. And after a few years no one needed it.

The story of VisiCalc, a modest spreadsheet program that exploded the tech world 40 years ago, has spread across the industry and still influences the decision-making process of directors, engineers, and investors. Among her lessons are the possibilities of simple solutions and the difficulty of creating an incredibly fast growing company within an incredibly fast growing industry.

Today, these lessons have so absorbed the titans of the technology industry that they have developed immunity against such noisy and competitive dynamics, which can also be called a disorder.

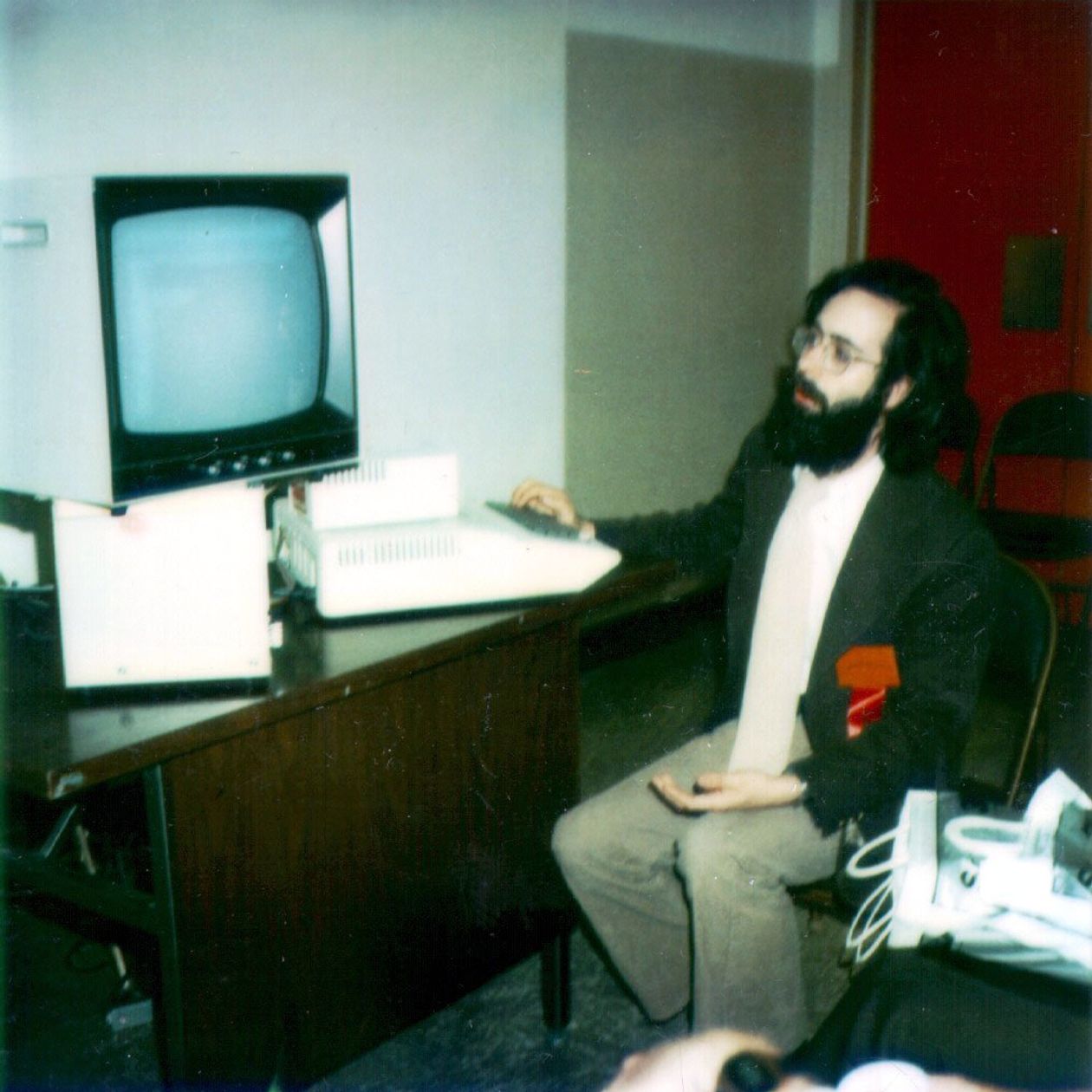

Dan Bricklin at the West Coast Computer Fair before a public presentation of VisiCalc

VisiCalc was introduced on June 4, 1979, and began selling in October of that year. For the first time, Dan Bricklin imagined it in the classroom of Harvard Business School - now in this audience there is even a plaque connected with this event - and joined forces with Bob Frankston, who wrote code for VisiCalc and participated in the development of its interface.

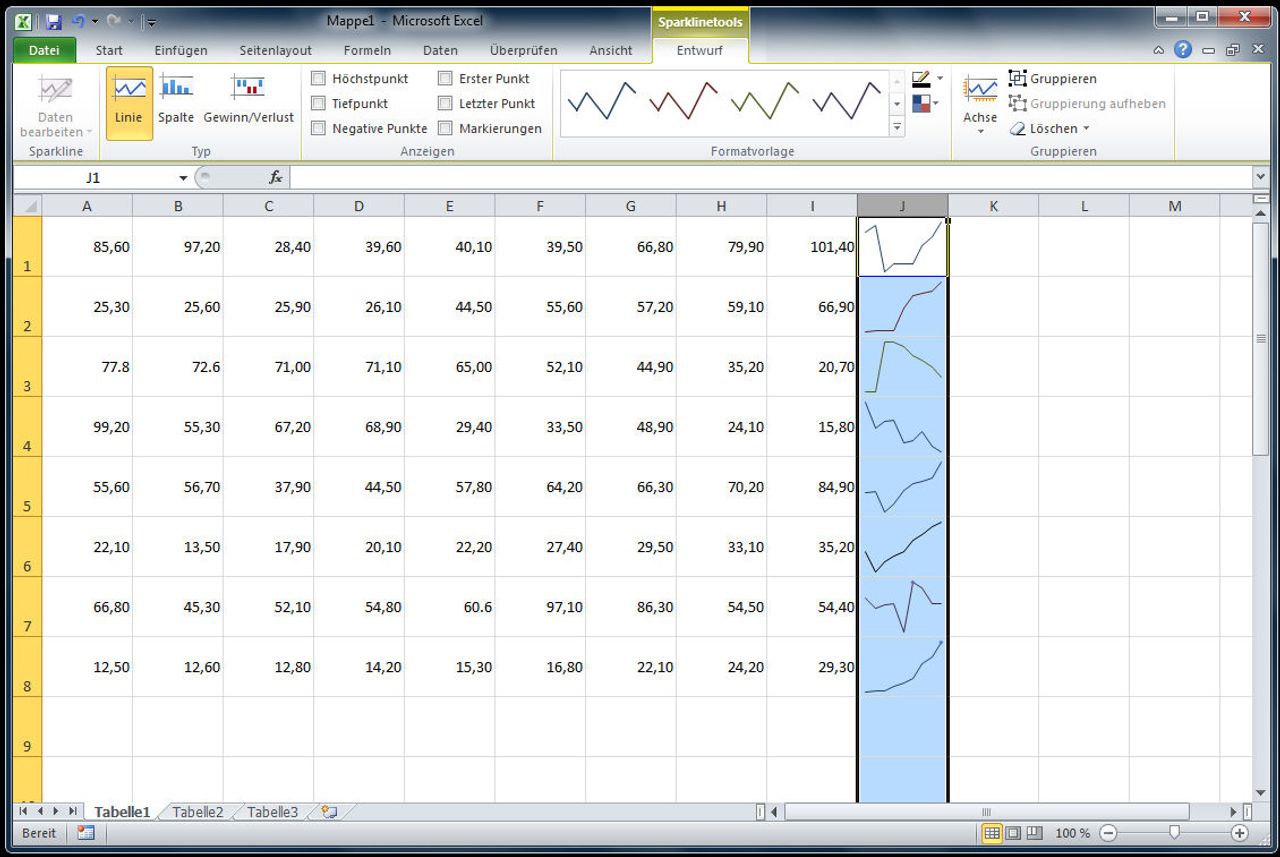

When the user opened VisiCalc, he saw a grid drawn with text characters in which he could manipulate numbers or text. She was well-suited for budgeting, finance planning, bookkeeping, and list building. Today, anyone recognizes in it a spreadsheet that we know as well as a blinking cursor, but at that time it was an innovative idea that needed to be seen in order to be aware.

VisiCalc initially only worked on Apple II, a personal computer that was considered revolutionary, and became Apple's first major consumer product. And while some Apple II models only had 4 KB of RAM, VisiCalc required an incredible 32 KB (even today's cheapest iPhone models have tens of thousands of times more RAM).

“It was a nice little program, but who would have expected it to come out of it?” Frankston recalls.

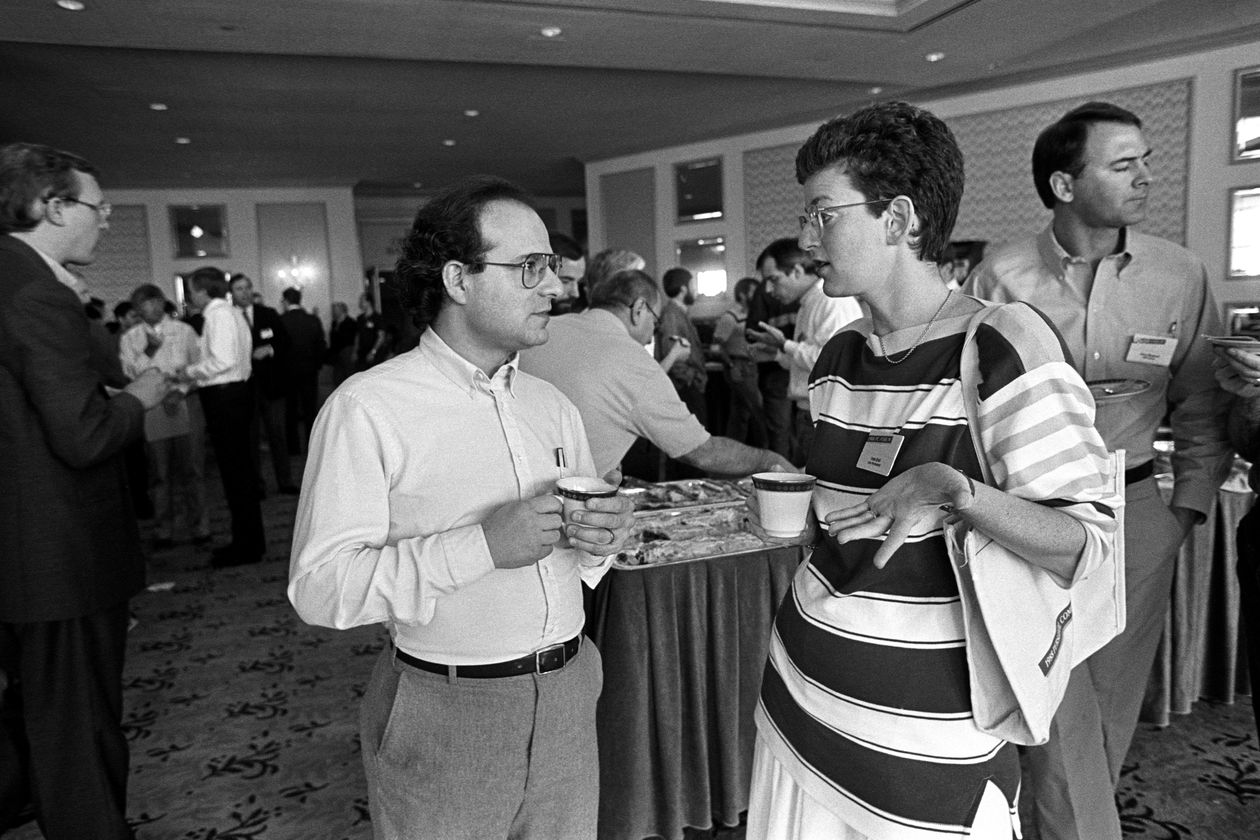

Frankston, left, in 1988

Steve Jobs later said that VisiCalc’s release “helped push Apple II to success more than any other event.”

VisiCalc was the first among the programs so popular that it was only because of them that people were ready to buy computers. A 1984 article for PC Magazine noted: “People went to computer stores to buy VisiCalc, and something to run it on.” At that time, VisiCalc was worth $ 100, and the Apple II computer could cost you $ 2,000 or more — much more. VisiCalc’s publisher’s profits, the overwhelming majority of which relate exclusively to the program itself, grew at an explosive pace, from small amounts in 1979 to over $ 40 million in 1983, said Edward Esber, former vice president of marketing for the company.

This was the first VisiCalc lesson: empires are built at the start of a new platform. In this case, the transition came from paper books, which accountants have used for centuries, to their digital equivalent on a PC.

The PC was probably the first modern technology platform - that is, such a thing whose value lies in the ability to use various types of programs and services - and most of what happened later became typical of each new computing platform that appeared later.

Unfortunately for Bricklin and Frankston, the second lesson of VisiCalc was that a killer application does not guarantee ongoing success. Software could be the first technological victim of what scientist Clayton Christensen would later call “disruptive innovation” - when a small company goes around the corner of recognized favorites, focusing on previously unnoticed markets.

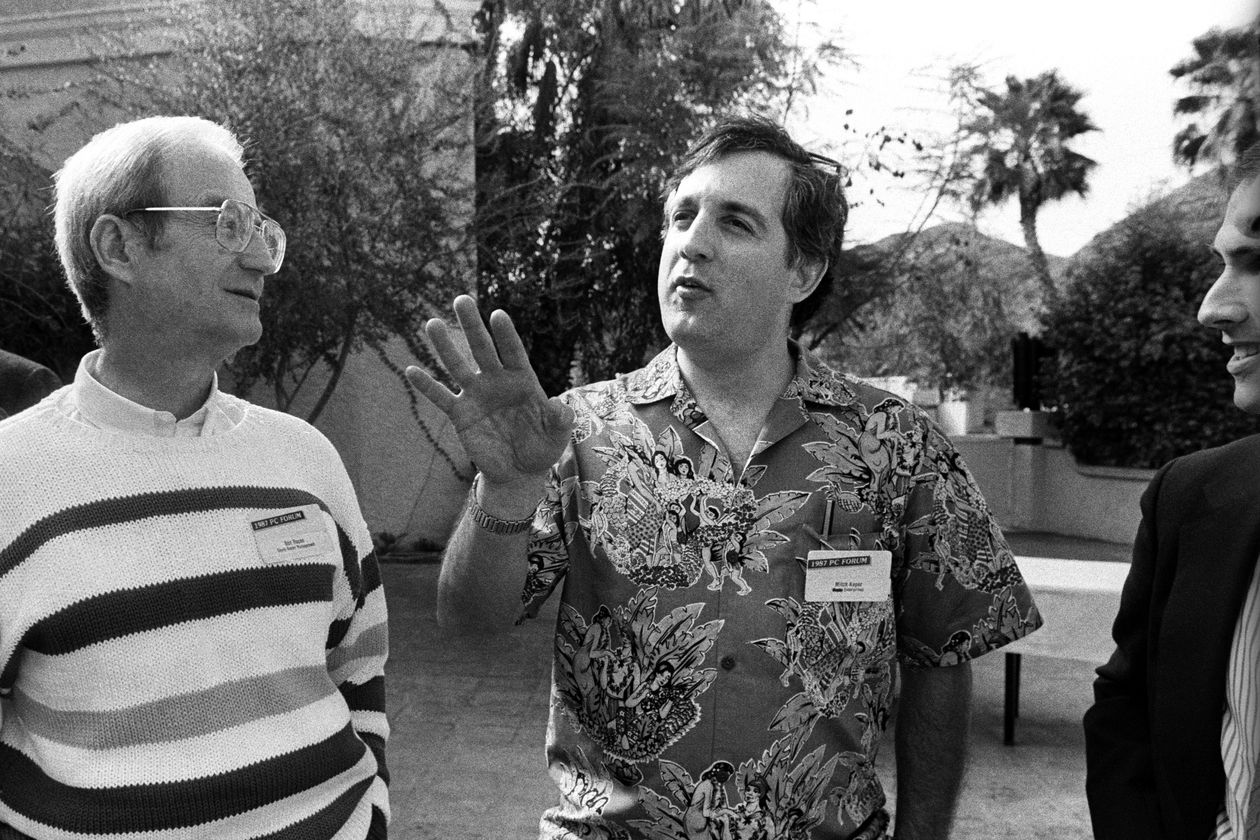

Mitch Kapor (center) used his knowledge of the spreadsheet market to launch the Lotus 1-2-3 program

Mitch Kapor, who worked with VisiCalc publisher as a product manager, left the company and began working on his own spreadsheet. But instead of making it for an Apple II computer, Kapor put his money on another horse: the latest IBM PC. His Lotus 1-2-3 program, released in 1983, took the world by storm on a scale that even VisiCalc could not predict.

“Most people sincerely thought it was a big risk, because Apple II was dominant in the market at the time,” said Kapor.

Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet program on a floppy disk

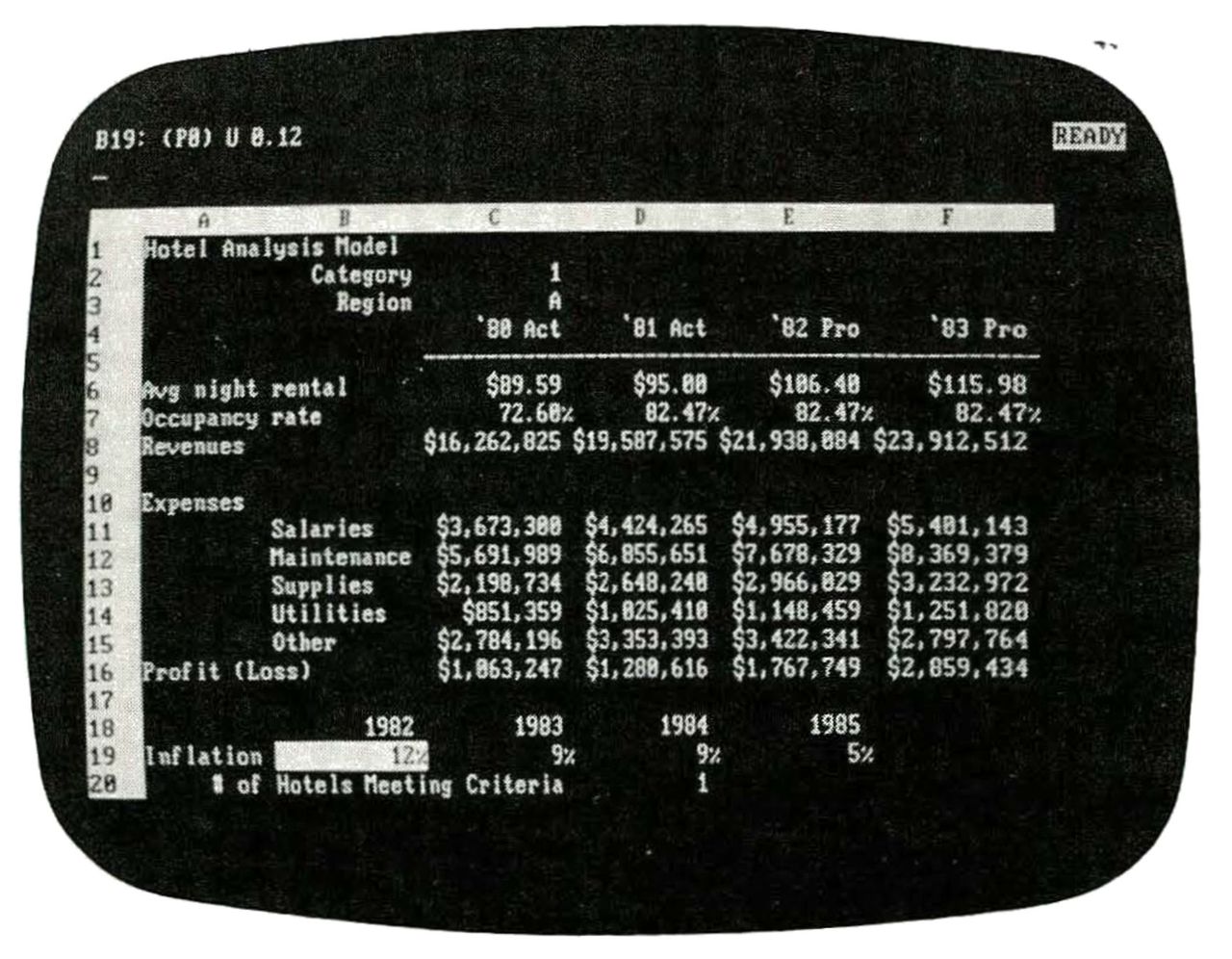

Lotus 1-2-3 had the basic capabilities of VisiCalc, and even allowed you to directly import files of its format. But she could do more. Kapor, who was well acquainted with the spreadsheet market, knew what users required. Lotus 1-2-3 could change the width of the columns, it had a macro language that allowed you to set simple programs for cells, and the ability to create graphs. She also worked fast.

Meanwhile, VisiCalc was mired in a lawsuit between creators and publishers - at first, software was distributed by author-publisher model, like books. And greed was probably one of the reasons why developers could not make money on the rise of IBM-compatible PCs.

In the year following the debut of the IBM PC, less than 100,000 were sold. During this time, Lotus 1-2-3 sold $ 54 million. After the second year, IBM sold 280,000 PCs, and Lotus sales rose to $ 156 million.

On pre-orders alone, the parent company Lotus Development won an incredible round of investment of $ 5 million in scale, and by 1983 it entered the stock exchange. A few years after its founding, thousands of people worked at Lotus.

VisiCalc

Lotus 1-2-3

Microsoft Excel for Apple 1986

Microsoft Office 2010

“At that time, we became the largest independent software company in the world, despite the fact that two years before that we were not there at all,” says Kapor.

The third lesson from VisiCalc and its followers is that the largest technology industry players today understand the threat of destruction, and do not let startups with innovative ideas challenge their dominance.

Today, when people following the trends notice a new platform, even the largest companies are seriously investing in it - especially if it can threaten disruption of their work, says Stephen Sinofsky, former head of Windows at Microsoft, a partner in venture investment firm Andreessen Horowitz.

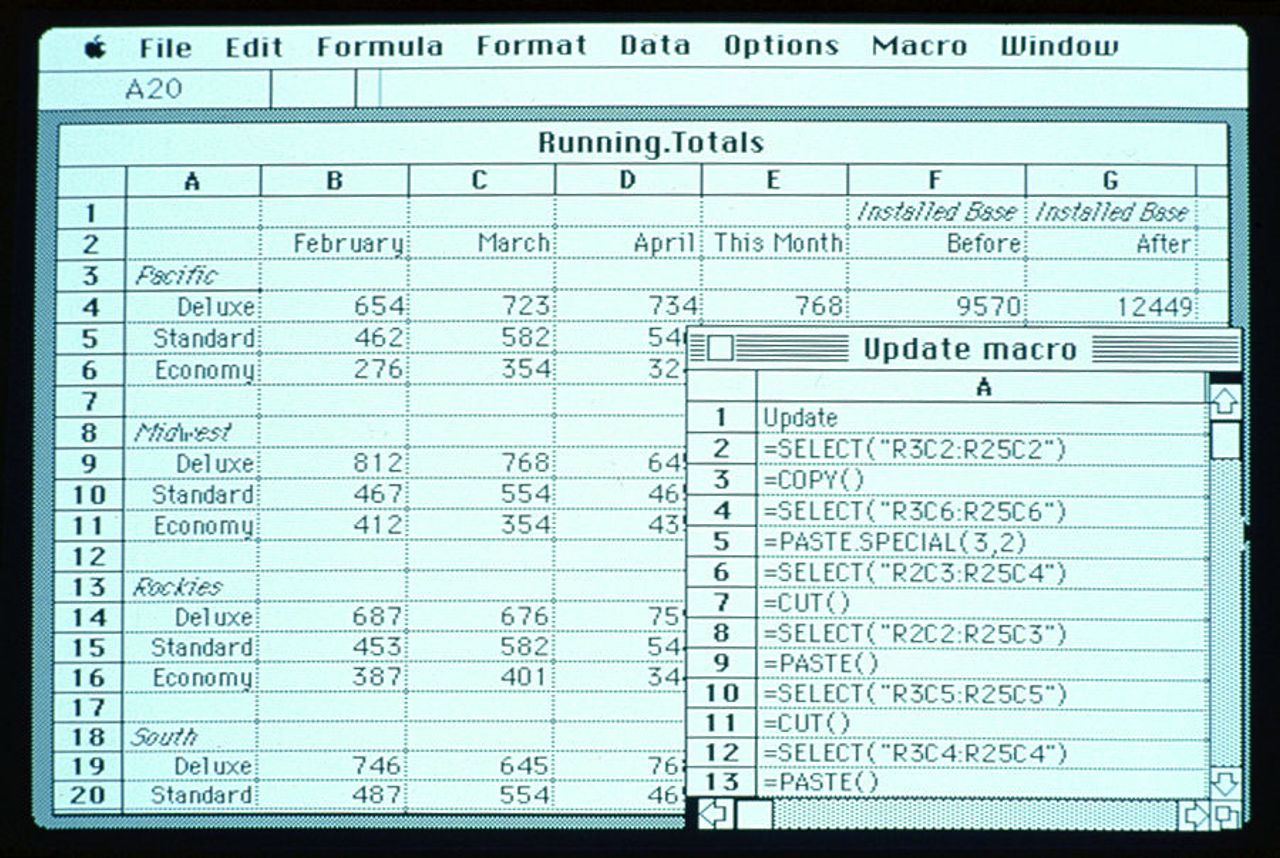

After Kapor stepped down as director of Lotus, the company focused on porting its product to IBM OS / 2, the operating system with which IBM tried to overtake Microsoft on PC, and missed the market shift towards Windows. This shift has occurred, for the most part, due to users demanding to provide them with the best system to run the best spreadsheets - in this case, Excel, which Microsoft announced for Windows in 1987.

Subsequently, Microsoft for the most part ruined all subsequent shifts of interest in other platforms, in particular in mobile computing. Recently, however, it has been able to successfully switch to cloud computing, adopting another “destructive” technology - evidence of the fact that this company is again the most expensive public company.

Today, one can often observe how companies are ahead of their potentially “destructive” technologies. The iPhone was born out of Apple’s paranoia about someone else eclipsing the iPod. Facebook, having acquired potential competitors Instagram and WhatsApp, has made the company's social platform dominant on mobile devices, where most of the social networks have moved. Amazon’s dominance in the market for automatic voice assistants is the result of the company's willingness to launch startups within itself and let them fail quickly - as happened with the Fire Phone - or outperform much larger competitors like Alexa, which came as a surprise to both Apple and Google. And Google, of course, was able to foresee the need to buy and invest heavily in the Android platform.

Of course, there are still examples of the emergence of new companies, but it’s rather difficult to imagine that several giants so towering above the technical world will allow themselves to share the fate of VisiCalc or Lotus. And the more money they accumulate to invest in new technologies, evenly distributing their bets all over the roulette wheel, the more invulnerable they seem.

All Articles