India cautiously looks to artificial intelligence

In India, technology outsourcing has been the only reliable way to create jobs in the past 30 years. Now, artificial intelligence threatens to destroy this advantage.

Two days after Sunil Kumar received the promotion, he received a call from the HR department and was asked to resign.

This happened in April, just as Kumar’s ninth year of work began at Tech Mahindra , one of the giant companies in the Indian IT industry. He worked in the engineering department, developing components and tools for aerospace companies in North America and Europe. Those sent specifications - materials available for the hinge, the permissible load, the cost of production - and he gave out options with the help of programs. He was an infantryman in the Indian army of engineers, whose work was outsourced from the West due to his penny value. Sometimes he left his workplace on the company's campus in Bangalore to work in overseas client offices: in Montreal, Belfast and Stockholm.

At the time of his dismissal, Kumar earned about $ 17,000 a year, a good middle-class wage for India. At about the same time, Tech Mahindra announced a profit of $ 419 million for the previous fiscal year, with revenues of $ 4.35 billion. Every year, Indian companies in the field of IT and related areas receive a total income of about $ 154 billion and employ nearly four million people . This sector has been fueling their ability to continuously reduce costs thanks to the possibility of hiring such inexpensive workers as Sanil Kumar.

Bangalore is full of IT professionals and engineers. His curly hair is thinning at the top and turning gray at the temples. When we talked to him, he wore a faded Tommy Hilfiger T-shirt and tried to hide his anxiety. He grew up in a village a few hundred kilometers from Bangalore, where his father spun silk saris on a hand spinning wheel. In 1995, at the age of 15, he moved to Bangalore to study for a mechanical engineer - a little less than a university degree, which he will receive later, after completing an appropriate course.

Before joining Tech Mahindra in 2008, Kumar worked as a draftsman at an aerospace company. The new work has given him new opportunities that the IT industry gives many Indians, offering to rise from the past of blue-collar workers to the future of whites . He married, he has a son; He borrowed $ 47,000 from the bank to buy a house so that his parents and two brothers who moved to Bangalore could live with him. “I live a middle class life,” he says. - I do not want to brag to people that I work in IT. I don't need branded T-shirts and shoes. ”

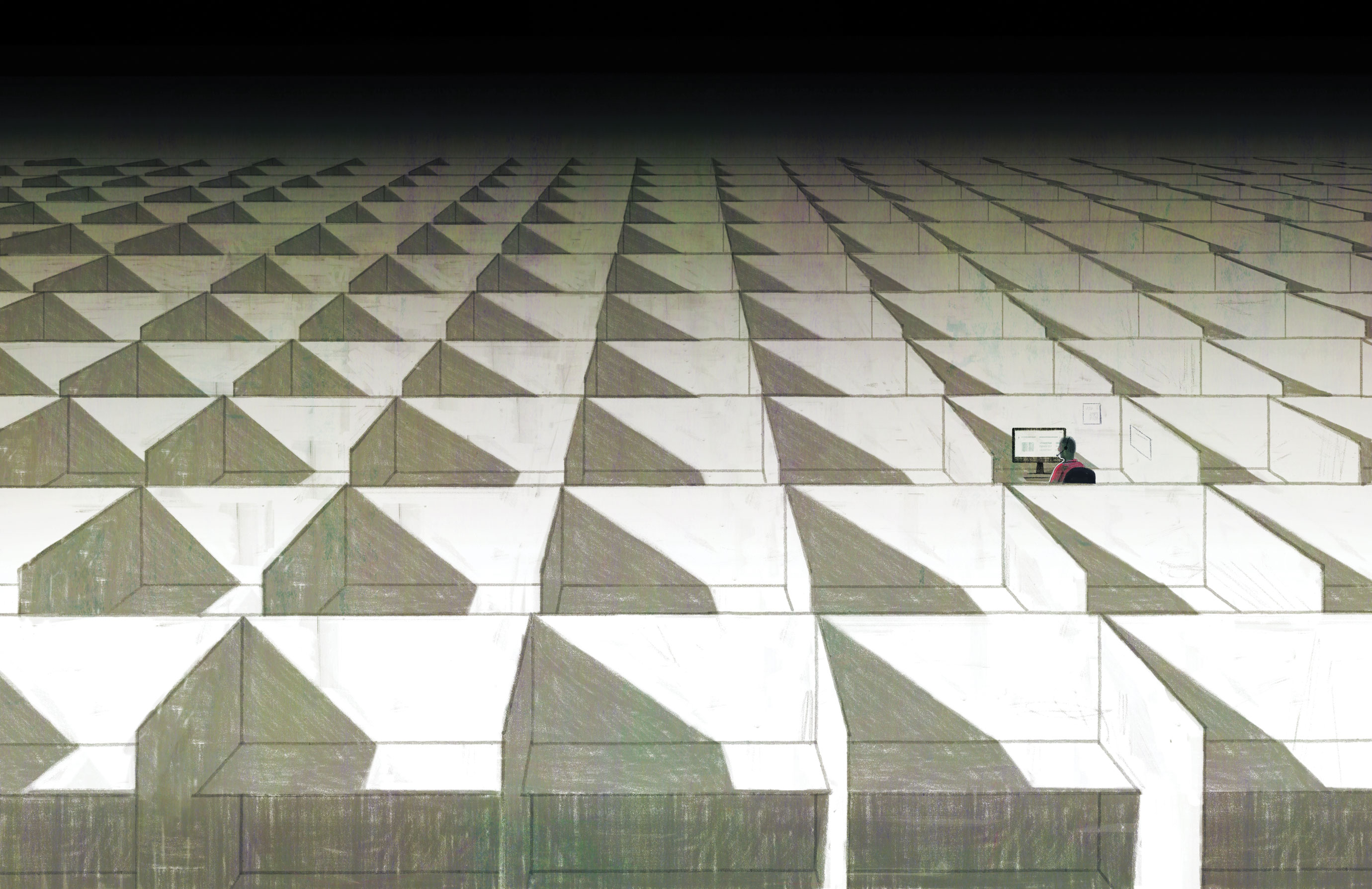

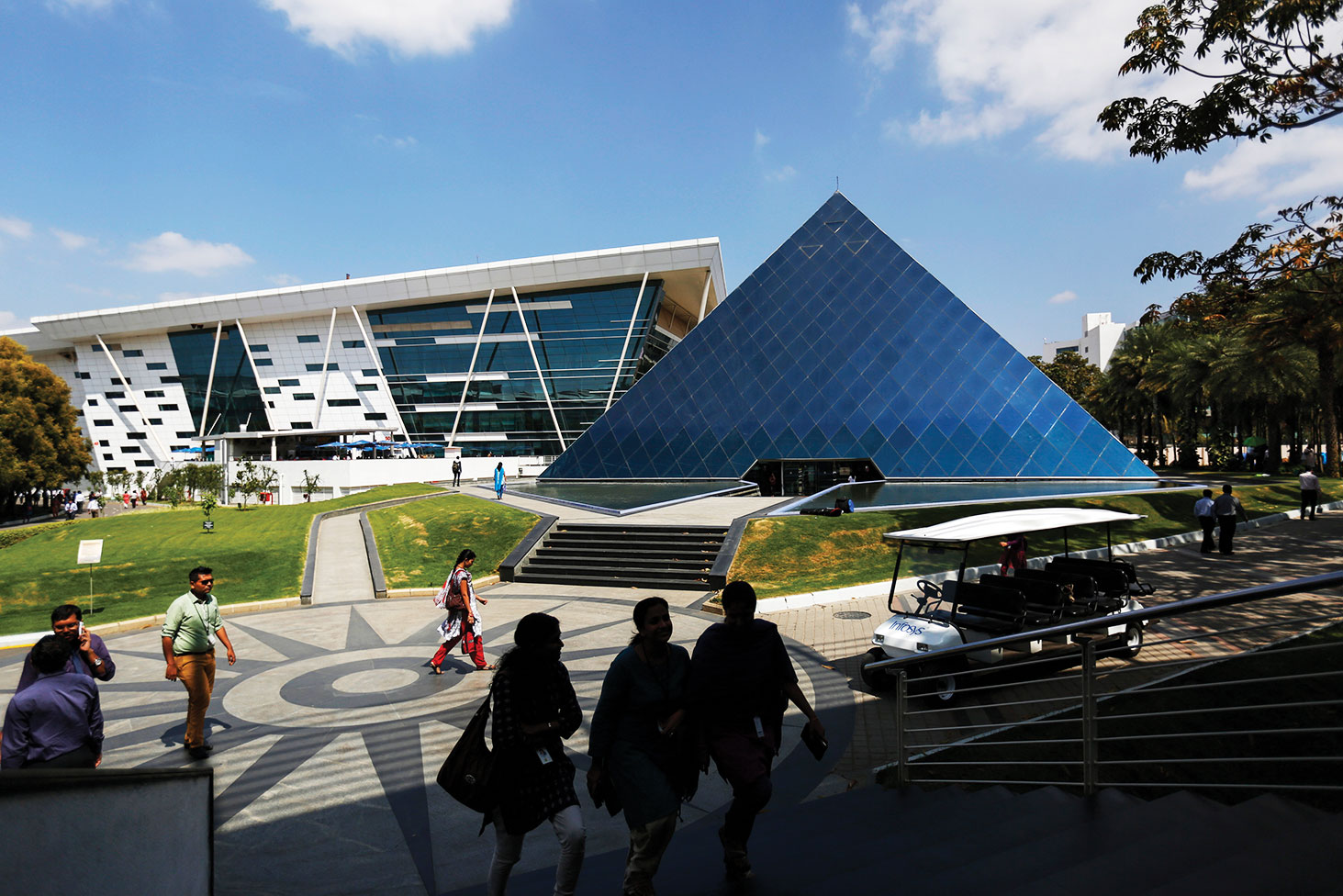

The size and prestige of the Indian IT industry is reflected in the design of Infosys campuses. From above - in Mysore, from below - in Bangalore.

Having lost his job, Kumar became part of a wave of laid-off workers running through the Indian IT industry — and this includes call centers, engineering services, business process maintenance firms, infrastructure management, and software manufacturing companies. The recent layoffs have become part of the largest wave in the industry since it was a sharp rise two decades ago. Companies do not always directly link these layoffs with automation, but at the same time, they constantly define automation as the beginning of huge changes in the industry. Bots, machine learning, algorithms that automatically execute processes, make old skills obsolete, change the idea of work and reduce the need for labor.

Analysis of the business newspaper Mint claims that the seven largest IT-companies in India in 2017 will fire 56,000 people. After the annual general meeting, the $ 10 billion giant Infosys announced that 11,000 people from their army of 200,000 employees “freed” automation from repetitive work, and therefore they were transferred to other positions within the company, while the burden of their old work carry the algorithms. The IT industry company HfS Research last year predicted that automation by 2021 would lead to the loss of 480,000 jobs in India. “If we sit back, there is no doubt that our work will be taken by the AI,” said Vishal Sikka in March, when he was still the general director of Infosys (he dismissed in August). "Over the next 10 years, and maybe faster, 60-70% of jobs will be taken by AI - if we do not continue to develop."

The fear that AI takes work is not unique to India, but India’s automation can be particularly harmful, since most of its high-tech economy depends on the relatively routine work that computers will select first. In some cases, IT companies automate their work. In others, Western companies will do this so that they no longer have to give jobs to people in India.

Sanil Kumar was not given a detailed account of why he was fired. He believes that his work at Tech Mahindra could not be automated, and that he was fired as a result of the company's internal changes. Devika Narayan, a sociologist at the University of Minnesota who studies this topic for his doctoral thesis, believes that automation can often be blamed for nothing in the loss of such jobs. She says the company can talk about automation to hide its problems, or to distract from other weaknesses that it cannot control. She points out that many IT giants are flabby and overgrown with too many people, and that American companies are wary of transferring work abroad due to the current political climate in the country. “I still cannot say how much the guilt of automation is exaggerated,” says Narayan. She suspects that Indian IT companies "want to use this talk of automation just to make structural changes and downsizing."

India is very important to understand where the truth is. The IT industry can provide jobs for only a few million out of 1.3 billion people - but it served as a beacon for young boys and girls with aspirations. She motivated families to send children to universities, had graduate students on shining campuses, gave them an independent urban lifestyle, provided a steady income and access to a world outside India. Over the past 30 years, it has been the only industry in India that has developed from scratch to similar success. In other areas, job creation in India is a problem: every year 12 million Indians join the ranks of workers, but in 2015 only 135,000 jobs were created in the eight largest sectors of the “white” economy, including IT. A drastic reduction in the IT industry - the attenuation of the lighthouse - will hit the economy and politics of the country.

Knocking out swivel chairs

Chetan Dyube says he foresaw this. In 2005, Dyube, director of IPsoft, spoke at the forum of IT-companies in Mumbai. “If the Indian industry is not aware of the impending wave of automation, we will face an existential crisis,” he recalls his speech. - I was criticized. The next day we had breakfast, and on the last pages of the Economic Times newspaper there was an article: “The IPsoft director predicts the death of Indian outsourcing.”

Dyube, a mathematician with a bow tie and suspenders, once taught at New York University, founded IPsoft in 1998, but the company launched its flagship product, Amelia, in 2014. Amelia, a robot consultant, should replace people who process user requests at call centers. Amelia has been used to resolve supplier issues in major oil and gas companies; it supports the online chat of the Swedish bank SEB; she works in another bank in the department of mortgage brokers. According to Dyube, one of the company's clients had an average time to connect with a support service worker from another country 55 seconds; and a copy of Amelia starts working in no more than 2 seconds. An outsourced employee took an average of 18.2 minutes to solve a problem; Amelia takes 4.5 minutes. The area of user support is quickly filled with such solutions - chat bots, which, through text or voice communication, eliminate the need for human presence.

Amelia directly replaced Indian workers in only a few cases, but Dyube believes that further changes cannot be avoided. Call centers in India are already changing: wages are not growing, work is hard, firms such as Infosys and Tata Consultancy Services have outsourced some of the functions to Manila, where labor costs are even lower than in India. Three years ago, one official of the ASSOCHAM trade association predicted that over the next ten years, India would lose $ 30 billion in profit centers to the Philippines. In the West, some companies are returning voice support, while others refuse it in favor of email and chat.

Revenue growth (above, billion dollars) and the number of employees (below) in the IT industry

Prospects — or fear — of automation have become another force that changes business call centers. Voice recognition has not yet reached the ideal , and even the most complex and laudable systems in the near future will not be able to deal with any customers, difficult problems or unusually strong accents. But most of the voice processing is prosy and routine. If we take into account that people at the first turn of the service give answers in accordance with a rigid scenario, their work is translated into machine code more easily than others.

A similar fate awaits another part of the sector - as Dube says, “India is just blue-collar IT sector”, so the bottom layer of work is filled with tasks that require diligence and endurance, but not creative approach or serious technical skills.

At Genpact, a company that has been around for 20 years and started working with business process outsourcing, before including other services in its field of activity, a lot of work for the occupants of “swivel chairs”, says Gianni Giacomelli, who leads the digital solutions department. This definition describes the mechanical nature of these tasks. Until recently, a person was needed to work with software systems that help implement industrial functions. These systems are often unrelated to each other, so Genpact employees “had to, in simple terms, handle things that went out of one system and went into another,” he says. “This is a tossing to and fro - a terrible waste of time.” Since 2014, Genpact has replaced workers in swivel chairs, giving computers a task to extract information from screens and servers and transfer them to other systems.

One level up is the work that Giacomelli calls “reconciling”: studying the accounts of suppliers and users of a client, and finding inconsistencies and contradictions. This is not a trivial job, and so far it requires decisions made by a person. “But when a car reconsiders enough examples, it can do that,” he says.

Chaos

For some of its customers, the IT colossus Infosys was able to automate almost all the tedious work of tracking and maintaining the data infrastructure, said Ravi Kumar, assistant chief operating officer. Also, the machines are already doing some intermediate work, such as sorting requests for support. At an even more difficult level of service - among the work on finding bugs in the depth of the program code or developing solutions to new problems - automation performs 35-40 percent of the work.

Somak Roy, an analyst at Forrester Research, estimates that now in India, machines perform only a quarter of the easiest to automate. Companies are enthusiastically tinkering with emerging technologies. Still, Roy talks about the "obvious possibility" that IT will no longer be a major supplier of jobs in India.

One of the clearest plans comes from Pankazh Bansal, the CEO of PeopleStrong, a recruitment firm that is often looking for technicians for IT companies. For the usual IT companies in India, according to Bansal, “chaos will come” in the future. He is accused of panicking, but he does not deviate from his point of view. He says that over the past two years, 3-4 out of every 10 jobs in the lower layer of the IT pyramid were taken away by automation - and this is not reflected in how many people were laid off, but how much the recruitment of new employees fell in volume. Companies used to run around engineering college campuses, harvesting fresh students out of the net. Bansal recalls that the IT sector annually hired 400,000 people, up to the time that occurred 2-3 years ago, and now this number has decreased to 140,000–160,000. He says that soon “hiring will be hardly more than zero” .

Bansala's predictions about the deflation of labor may come true for another reason. For years, IT firms have hired low-cost young laborers in bulk — even without special skills — because it made sense to fill projects with people. The more people working on the task, the more you can bill the client. But such a calculation of the size of the check is declining, now customers are paying for the result. In the meantime, young people without skills, remaining in firms, regularly received promotions and increases, until they turned into middle-class engineers, thousands of whom had become too costly to support. Hence the cleansing.

Bansal’s gloomy predictions are not shared by other industry workers, at least publicly. This is understandable: it is not right for companies to loudly proclaim the inevitability of redundancies and layoffs. Sangita Gupta, senior vice president at the National Association of Software and Services Companies, predicts only a “gap” between the number of workers and the size of profits in the next few years. If the Indian IT industry needed three million workers to earn $ 100 billion annually, she says, then in order to add another $ 100 billion to the profit, it will need from 1.2 to 2 million people additionally. By 2025, when profits reach $ 350 billion, Gupta predicts, another 2.5–3 million jobs will appear in the sector in addition to the current 3-4 million.

Companies are in a hurry to explain why automation not only does not clean out, but also multiplies the ranks of employees. Machines, for example, cannot overnight make people unnecessary. “The works are not structured in such a clear way,” says Giacomelli from Genpact. The architecture of modern work, which has developed over decades, contains people in its center. It depends on the flexibility of people and their ability to reflect on different things. “People are universal, so it’s not so easy to isolate one task or another and transfer it to the AI,” he says.

Companies also insist that they want to retrain employees at risk of being replaced by automation. If the engineer’s job is better done by the algorithm, it’s “unfair to say to him:“ You don’t have any more work, ”says K.M. Madhusudhan, Technical Director of Mindtree, a service company with more than 16,000 employees. “Is it possible to teach an engineer to program? Maybe not something complicated, but at least scripts, it is not so difficult. We believe that in each role there are higher level related skills that can be mastered. ” Madhusudhan calls this a “humanitarian approach.” Thanks to him, fewer jobs will disappear, although he admits that firms like his will probably create fewer new jobs. “The number of jobs that was before will be unattainable in the future,” he says. “This is a matter of serious concern in a country like India, because we are still producing a lot of engineers, and not all of them will get the job.”

Historically, the scheme is familiar: every technological breakthrough meant that fewer people could now do the same job. “With each revolution, there is concern about reducing the number of jobs. This was the case during the industrial revolution, ”says Infosys Ravi Kumar. - In fact, there is an increase in consumption. And this ultimately increases the demand for new types of work. Now, according to him, large firms spend 65-70% of the budget just to “burn the light” - to pay for infrastructure and routine support. If you release these funds, they can be poured into new ones - it is still difficult to imagine which are the flows of generating profits and jobs: “for us it would be a completely different picture.”

But even if he is right, there is tension due to the difference between the long progress of these revolutions and the short lifetime of a person. In the short term, people will lose their livelihoods. Sanil Kumar has not yet found a job.

In June, he sent a complaint about wrongful dismissal addressed to the Labor Commissioner, to an institution that deals with industrial disputes and support for the labor law. When he decided to check how the case was moving, the official told him that this battle would most likely be a long one, and now he suspects that it will lead nowhere. “I lose the confidence that I had,” he says. Reading newspapers, he does not reach the pages devoted to business - they upset him. "There will be a lot of companies writing something like" We hire so many people, they have so many opportunities. " The directors say it all the time. I stopped reading all this, ”he says. He knows that he must look for a new job, but he cannot take himself in hand; it seems that his dismissal drove him to a standstill. “I can't concentrate on anything,” he says. “It has become very difficult to do.”

All Articles