"Flugegehaymen" or the study of circadian rhythms through thermorectal sounding

One of the previous articles dealt with circadian cycles and their synchronism with body temperature. Today I want to continue this topic, and for this we turn again to experiments on people.

So welcome to 1970.

It was at this time in Montefiere, in the Bronx, that Elliot Weizmann and his student Charles Chasler decided to conduct a series of experiments in isolation from time.

In their arms were: the old hospital building, soundproof rooms with no windows, twelve volunteers found through the newspaper, a budget of several thousand dollars and rectal probes for temperature measurement.

Not that it was a necessary reserve for experiments, but if you decided to start learning circadian rhythms, it becomes difficult to stop. The only thing that could cause fear among volunteers is rectal probes.

There is nothing more helpless and pitiful than an experimental volunteer with a rectal probe, which is forbidden to extract. Everyone knew that sooner or later complaints would start against them, but their testimony was necessary for research.

Before the start of the experiment, scientists had to prepare. For work, they chose a room on the fifth floor of the hospital, where they soundproofed several rooms and closed them from daylight. Experimental premises consisted of three rooms for experimental and control room in the center.

The next step was to find volunteers. Scientists placed an ad in the newspaper, and they focused on students, artists and graduate students. Why exactly these categories of people - one day of the experiment cost about $ 1,000, and therefore it was necessary to find people who were accustomed to bring the work to the end, and it was also the representatives of these categories who could find work that would not only interfere, but would help from the world for three to six months. Also, the subjects expected a psychological test, because scientists did not want to allow the premature completion of the experiment because of the sliding roof of someone from the experimental.

Of the good news for the subjects - they were waited not only by the opportunity to do any project, not being distracted by the world around them, but also by material compensation of several hundred dollars a week, and this is a considerable amount considering the 70th year. They were also provided with comfortable housing, high-quality food and no restrictions on pastime. They could go to bed and wake up whenever they want, no one forbade reading books and newspapers or listening to music. Also, communication of the subjects with each other and even with laboratory assistants, in contrast to Siffre, was not excluded.

The ban was a clock, radio, television and phone calls. Newspapers could only be with long-past publications. The purpose of such prohibitions is to isolate the subjects from external broadcasting of the current time. Also, for the accuracy of the experiment, alcohol, coffee and tea, drugs and sleeping pills, stimulants and other substances that could affect the cycle of sleep and wakefulness were banned.

By the way, earlier experiments on animals have shown that caffeine and alcohol can change circadian rhythms, although to a lesser extent than sedatives and stimulants.

So day after day, Chazler and Weizman, conducting an experiment, measured the level of hormones and the change in body temperature. To measure hormones, a catheter was inserted into the arm of each test subject, blood samples were taken every 20 minutes, and to record changes in body temperature, a rectal probe, which was forbidden to be removed except during showering and masturbation.

Also during the test, brain waves were recorded during sleep and wakefulness.

We should also mention the requirements for laboratory technicians. The first requirement was to exercise vigilance - in order to avoid accidental mention of the time of day, we greeted each other, always using only: “Hello!”. Male lab technicians always had to be clean-shaven so that the bristles would not betray the onset of the evening. And the distribution in shifts was random.

Here are the memories of one of the participants in the experiment:

In the first dozen of the subjects, six of them had an internal synchronization. For some reason they could sleep very long, time after time, with them the same thing happened with Siffre. For some, this strange 40-hour mode was maintained until the very end of the experiment. For other experimental subjects, long cycles of sleep and wakefulness alternated with short ones, and then they could return to normal 26-hour cycles. At first it seemed that this would not be able to find a logical explanation.

Scientists tried to find a connection between the 15-hour sleep and long-term wakefulness, but having built dependency graphs, they were disappointed - many examples were found when long periods of wakefulness alternated with a short sleep and vice versa.

But the graphs of body temperature and hydrocortisone production, as well as the reaction rate always remained unchanged and were a little more than 24 hours.

Perhaps the clue to circadian rhythms was here.

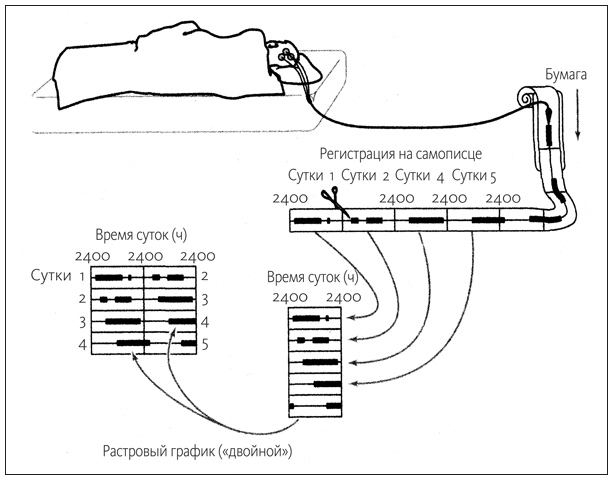

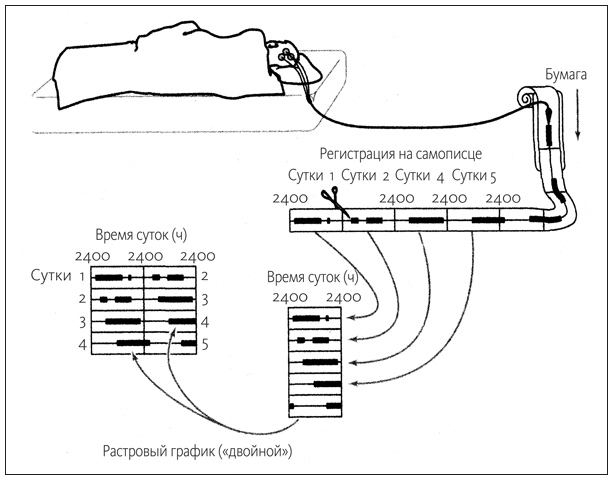

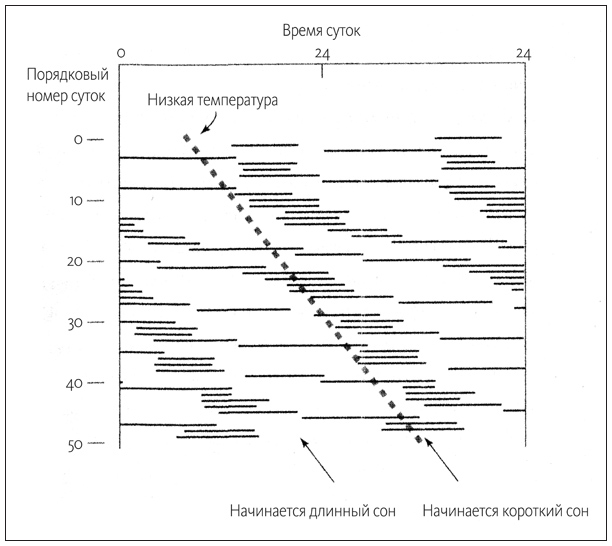

Meanwhile, Chasezle continued his attempts to find a relationship between wakefulness and body temperature. In this, he was helped by the construction of a raster graph, which was previously used by biologists to track the cycles of leaf opening of plants and activity rhythms in laboratory mice, but never before in studies conducted on humans.

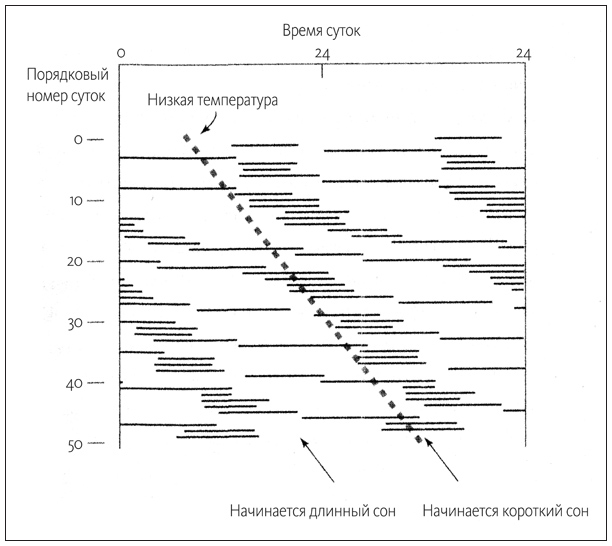

After plotting one of the out-of-sync subjects, it was noticed that the episodes of short and long sleep were lined up along the temperature diagonal, which was superimposed above.

From this it was concluded that although, at first glance, sleep and wake cycles do not depend on temperature, there is a clear link from the graph - prolonged sleep episodes always begin at high body temperature, and short-term - at low. After finding this connection, Chayzler analyzed the old data from previous studies that were conducted in France, Germany and England, and his findings were confirmed.

It was a clue to the circadian cycle!

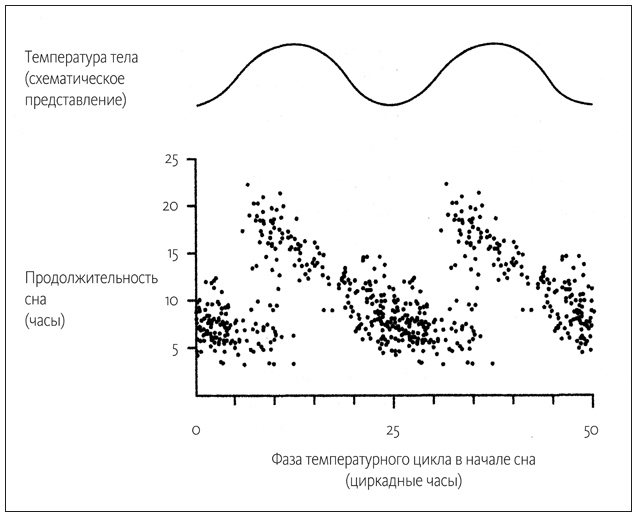

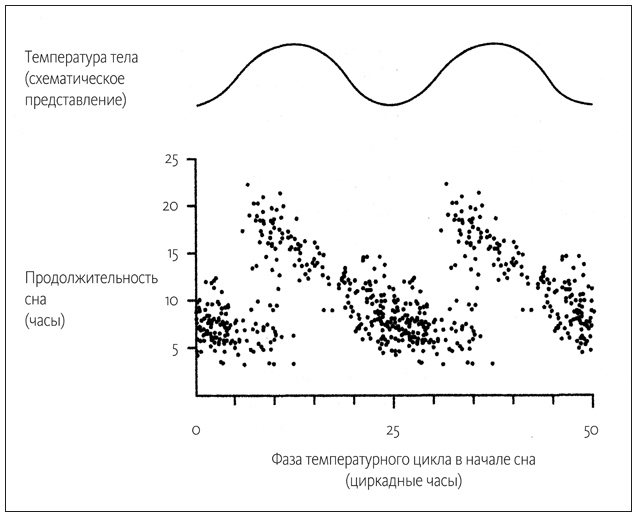

To concretize the conclusions was built another graph. In it, Chayzler took all the “cold” sleep episodes and grouped them together, and then did the same with sleep periods starting near the maximum temperature. And despite the striking individual differences in the cycles of the subjects, and they could be both 20-hour and 40-hour, the duration of sleep was grouped in a narrow range and formed a certain mathematical curve.

Each time falling asleep near the temperature peak, the subjects waited for a long sleep for an average of 15 hours. And staying up to sleep near the temperature minimum - about 8 hours.

And although such conclusions seem illogical, if we follow the linear law, the subjects slept less, although they were more awake than they were sleeping with considerable delay compared to the temperature cycle. Later, the same dependencies were found in people working at night. So you might have noticed that often falling asleep late and hoping to sleep a little longer, you wake up after 5-6 hours.

It's all about our internal temperature alarm clock - it will begin to ring no matter what time we go to bed.

In people involved in 24-hour sleep and wakefulness, body temperature reaches its minimum about two hours before the usual awakening and begins to rise. Hence, it turns out that the temperature minimum for people waking up at 6-7 am is 4-6 hours. A long jump in sleep will come in about ten hours, somewhere in the afternoon.

Siesta!

At this point I will finish, and I invite everyone to discuss or add to the article in the comments.

All stable circadian cycles and healthy sleep!

Literature:

“The rhythm of the universe. How out of chaos there is order in nature and in everyday life "

“The rhythm of the universe. How out of chaos there is order in nature and in everyday life "

Posted by: Stephen Strogac

Mann, Ivanov and Ferber, 2017

ISBN: 978-5-00100-388-5

So welcome to 1970.

It was at this time in Montefiere, in the Bronx, that Elliot Weizmann and his student Charles Chasler decided to conduct a series of experiments in isolation from time.

In their arms were: the old hospital building, soundproof rooms with no windows, twelve volunteers found through the newspaper, a budget of several thousand dollars and rectal probes for temperature measurement.

Not that it was a necessary reserve for experiments, but if you decided to start learning circadian rhythms, it becomes difficult to stop. The only thing that could cause fear among volunteers is rectal probes.

There is nothing more helpless and pitiful than an experimental volunteer with a rectal probe, which is forbidden to extract. Everyone knew that sooner or later complaints would start against them, but their testimony was necessary for research.

Before the start of the experiment, scientists had to prepare. For work, they chose a room on the fifth floor of the hospital, where they soundproofed several rooms and closed them from daylight. Experimental premises consisted of three rooms for experimental and control room in the center.

The next step was to find volunteers. Scientists placed an ad in the newspaper, and they focused on students, artists and graduate students. Why exactly these categories of people - one day of the experiment cost about $ 1,000, and therefore it was necessary to find people who were accustomed to bring the work to the end, and it was also the representatives of these categories who could find work that would not only interfere, but would help from the world for three to six months. Also, the subjects expected a psychological test, because scientists did not want to allow the premature completion of the experiment because of the sliding roof of someone from the experimental.

Of the good news for the subjects - they were waited not only by the opportunity to do any project, not being distracted by the world around them, but also by material compensation of several hundred dollars a week, and this is a considerable amount considering the 70th year. They were also provided with comfortable housing, high-quality food and no restrictions on pastime. They could go to bed and wake up whenever they want, no one forbade reading books and newspapers or listening to music. Also, communication of the subjects with each other and even with laboratory assistants, in contrast to Siffre, was not excluded.

The ban was a clock, radio, television and phone calls. Newspapers could only be with long-past publications. The purpose of such prohibitions is to isolate the subjects from external broadcasting of the current time. Also, for the accuracy of the experiment, alcohol, coffee and tea, drugs and sleeping pills, stimulants and other substances that could affect the cycle of sleep and wakefulness were banned.

By the way, earlier experiments on animals have shown that caffeine and alcohol can change circadian rhythms, although to a lesser extent than sedatives and stimulants.

So day after day, Chazler and Weizman, conducting an experiment, measured the level of hormones and the change in body temperature. To measure hormones, a catheter was inserted into the arm of each test subject, blood samples were taken every 20 minutes, and to record changes in body temperature, a rectal probe, which was forbidden to be removed except during showering and masturbation.

Also during the test, brain waves were recorded during sleep and wakefulness.

We should also mention the requirements for laboratory technicians. The first requirement was to exercise vigilance - in order to avoid accidental mention of the time of day, we greeted each other, always using only: “Hello!”. Male lab technicians always had to be clean-shaven so that the bristles would not betray the onset of the evening. And the distribution in shifts was random.

Here are the memories of one of the participants in the experiment:

“When I finished the school year in college, I felt deadly tired, and participation in this experiment was a chance for me to earn good money and pull up the“ tails ”of study. During the month of the experiment I managed to do more than the last semester.

They take my blood for analysis every fifteen minutes. A catheter is inserted into my arm, and a probe is in my ass. All these gizmos are connected to a moving pole. The first few days I was a little strained, but then I got used to it, and it began to seem to me that my tail had grown.

I never knew what time it was, but, to tell the truth, I didn’t even think about it. One day, when someone from the laboratory assistants came to me with a completely tired and wrinkled face, I told him: “It was not an easy night, was it?”

In the first dozen of the subjects, six of them had an internal synchronization. For some reason they could sleep very long, time after time, with them the same thing happened with Siffre. For some, this strange 40-hour mode was maintained until the very end of the experiment. For other experimental subjects, long cycles of sleep and wakefulness alternated with short ones, and then they could return to normal 26-hour cycles. At first it seemed that this would not be able to find a logical explanation.

Scientists tried to find a connection between the 15-hour sleep and long-term wakefulness, but having built dependency graphs, they were disappointed - many examples were found when long periods of wakefulness alternated with a short sleep and vice versa.

But the graphs of body temperature and hydrocortisone production, as well as the reaction rate always remained unchanged and were a little more than 24 hours.

Perhaps the clue to circadian rhythms was here.

Meanwhile, Chasezle continued his attempts to find a relationship between wakefulness and body temperature. In this, he was helped by the construction of a raster graph, which was previously used by biologists to track the cycles of leaf opening of plants and activity rhythms in laboratory mice, but never before in studies conducted on humans.

After plotting one of the out-of-sync subjects, it was noticed that the episodes of short and long sleep were lined up along the temperature diagonal, which was superimposed above.

From this it was concluded that although, at first glance, sleep and wake cycles do not depend on temperature, there is a clear link from the graph - prolonged sleep episodes always begin at high body temperature, and short-term - at low. After finding this connection, Chayzler analyzed the old data from previous studies that were conducted in France, Germany and England, and his findings were confirmed.

It was a clue to the circadian cycle!

To concretize the conclusions was built another graph. In it, Chayzler took all the “cold” sleep episodes and grouped them together, and then did the same with sleep periods starting near the maximum temperature. And despite the striking individual differences in the cycles of the subjects, and they could be both 20-hour and 40-hour, the duration of sleep was grouped in a narrow range and formed a certain mathematical curve.

Each time falling asleep near the temperature peak, the subjects waited for a long sleep for an average of 15 hours. And staying up to sleep near the temperature minimum - about 8 hours.

And although such conclusions seem illogical, if we follow the linear law, the subjects slept less, although they were more awake than they were sleeping with considerable delay compared to the temperature cycle. Later, the same dependencies were found in people working at night. So you might have noticed that often falling asleep late and hoping to sleep a little longer, you wake up after 5-6 hours.

It's all about our internal temperature alarm clock - it will begin to ring no matter what time we go to bed.

In people involved in 24-hour sleep and wakefulness, body temperature reaches its minimum about two hours before the usual awakening and begins to rise. Hence, it turns out that the temperature minimum for people waking up at 6-7 am is 4-6 hours. A long jump in sleep will come in about ten hours, somewhere in the afternoon.

Siesta!

At this point I will finish, and I invite everyone to discuss or add to the article in the comments.

All stable circadian cycles and healthy sleep!

Literature:

“The rhythm of the universe. How out of chaos there is order in nature and in everyday life "

“The rhythm of the universe. How out of chaos there is order in nature and in everyday life "

Posted by: Stephen Strogac

Mann, Ivanov and Ferber, 2017

ISBN: 978-5-00100-388-5

All Articles