Why are the biggest bitcoin miners in China

The bitcoin center has moved to Inner Mongolia , in which dirty coal feeds complex semiconductor devices

When I arrive at my destination in Ordos prefecture in Inner Mongolia, it is still 8 am, but the air is already heavy and depressing hot. My host drives us through the gates, past the sleepy guard and into the industrial courtyard, stretching across the dry and deserted countryside, as far as the eye can see.

In front of me are nine warehouses with bright blue roofs, each of which features the logo of Bitmain, a Chinese company headquartered in Beijing - probably the most influential company in the bitcoin industry. Bitmain sells bitcoin mining devices - special computers that use cryptocurrency software, and which produce, or “mineat,” new bitcoins for their owners. They also use their own equipment in factories that they own in whole or in part. Bitmain owns this factory by 20%.

Jihan Wu, director of Bitmain, declares that 70% of all the Bitcoin mining devices working today are made by his company. According to a study conducted by Cambridge University last winter, most likely, most of these machines are plugged into an outlet somewhere in China.

Bitmain bought this factory for mining in Inner Mongolia a couple of years ago, and turned it into one of the most powerful money factories in the Bitcoin network. It literally turns electricity into money. According to my calculations, their hardware - about 21,000 computers - are responsible for 4% of the total computing power of the Bitcoin network.

Like a ten-ton paperweight, these machines put pressure on the distributed transaction database, which Bitcoin represents, without letting its pages turn back. This is where the security of existing Bitcoin stocks is ensured. This is where new ones are born.

The bitcoin mining process works like a lottery. Miners compete in the production of hashes - fixed-length alphanumeric strings, calculated from arbitrary-length data. They produce hashes by combining three pieces of data: new bitcoin transaction blocks; last blockchain block; random number. All of this is generally referred to as the “block header” for the current block. Every time miners perform hashing of the block header with a new random number, they get a new result. To win the lottery, miners need to find a hash, starting with a certain number of zeros.

The number of zeros varies according to the amount of computing power connected to the set. On average, every two weeks, the mining software corrects the number of leading zeros — the level of complexity — by studying the rate at which new transaction blocks are added. The algorithm attempts to achieve a delay of 10 minutes between the blocks. When miners increase the computing power of the network, they temporarily increase the speed of creating blocks. The network tracks change and increases complexity. When the miner's computer finds a winning hash, it distributes the block header to its neighbors on the network, which it checks and distributes further.

Then two things happen. A new transaction is added to the distributed database, the blockchain, and the winning miner is awarded new Bitcoins. It also receives a small percentage that users add to their transactions as they wish in order to move them closer to the top of the queue. In fact, this is an exchange of electricity for coins, mediated by huge amounts of computation. The probability of winning the lottery for a particular miner is determined by the speed with which he can produce new hashes in relation to the speed of all other miners. It looks like a lottery with tickets, where the more tickets you buy, the more likely your name will be drawn out of a hat.

All this led to the race of miners for the accumulation of the fastest and most energy-efficient chips. Requests for faster hardware spawned a new industry dedicated exclusively to the computational needs of Bitcoin miners. Until the end of 2013, regular graphics cards and FGPA were powerful enough to race. But this year, companies began selling special-purpose integrated circuits (ASIC), sharpened to work with a bitcoin hashing algorithm. Today, ASIC is the standard for large factories, including the Ordos farm. When Bitmain first started producing ASIC in 2013, there were many competitors in this area: BitFury, the multinational ASIC manufacturer; KnCMiner from Stockholm; Butterfly Labs in the USA; Canaan Creative in Beijing; and about 20 more Chinese companies.

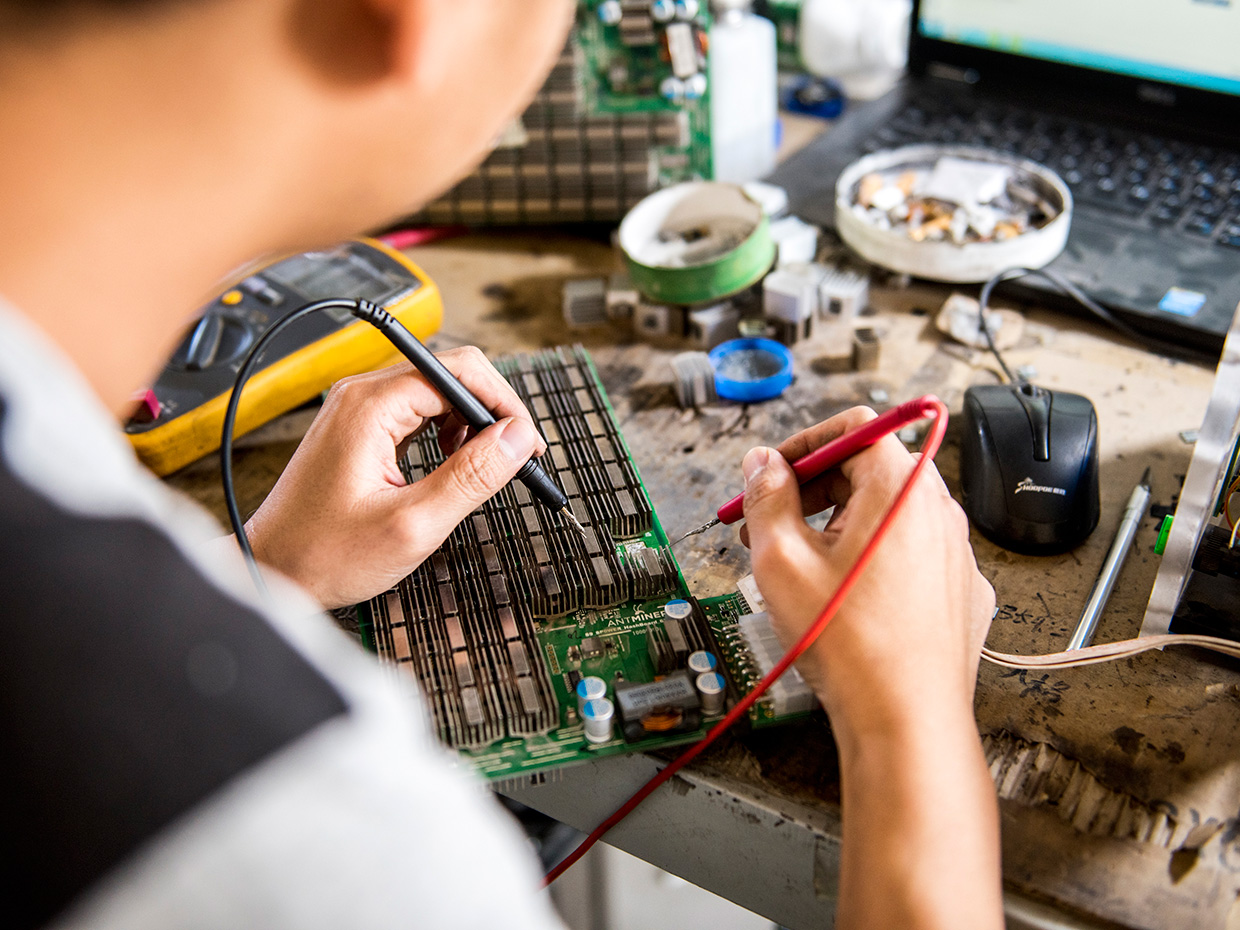

Bitmain pulled ahead, offering products of the best quality in large quantities, with which others could not cope. The Ordos factory almost fully utilizes the best Bitmain equipment, the Antminer S9. According to the company's specifications, S9 can grind 14 terahashi, or 14 trillion hashes per second, consuming 0.1 J per gigashash, which is a total power of 1,400 W (which is comparable to a microwave).

Although BitFury claims it produces almost the same efficiency as S9 chips, the company has packaged them into a completely different product. It is called BlockBox - this is a whole mining data center delivered to customers in a shipping container. Beijing's Canaan Creative still sells mining devices to a wide range of people, but offers only one product, the AvalonMiner 741 is twice as powerful and not as efficient as the S9.

The Antminer S9 consists of 189 ASIC chips manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (the world's largest factory) on a 16-nm process technology.

Each ASIC chip contains more than 100 cores, independently performing SHA-256 hashing algorithms. The control panel at the top of the machine coordinates its work, downloads the block header for hashing, and distributes the task among all components, telling it about the solutions found and the random numbers used.

“It’s like an ant colony, where the control panel is the womb controlling the workers,” says Peter Holm, director of integrated circuit design at Bitmain, explaining the origin of the name.

All the ASICs working on mining perform essentially similar calculations — the SHA-256 hashing algorithm — although they approach it a little differently. 64 steps are required to complete the standard algorithm, but in the case of Bitcoin, it works twice for each block header, which means there are 128 steps that actively use integer addition. “This dictates the whole scheme,” says Timo Hanke, chief cryptographer from String Labs, an incubator from Palo Alto. “If someone wants to optimize it, he needs to optimize addition. The main work is going on in this area. ”

In Inner Mongolia, one of the lowest electricity prices (4 US cents per kWh, thanks to government subsidies) is why miners are based here. But the climate outside the premises Bitmain terrible, especially in summer.

Despite similar needs, there is a wide variety of schemes that solve the hashing problem, says Hanke, who previously worked as the technical director of the now-closed manufacturer of mining equipment, CoinTerra. For example, Bitmain uses pipelining — a strategy that makes up a chain of process steps in which the output of one step is the input for another. A Bitmain competitor, BitFury, abandoned this technology.

The main problem in developing mining chips is energy efficiency, since your profit is the difference between the money spent on electricity and the bitcoins you have won.

“Energy is more important than rated speed. You are not developing chips for maximum speed, you are developing them for maximum energy efficiency, ”says Hanke.

If you do everything right, you also consider the need to cool the chips. S9 should operate at temperatures below 38 ° C. The controller at the top of the machine measures the ambient temperature and adjusts the fan speed, voltage and clock frequency.

But these measures are not enough if you mine in Inner Mongolia.

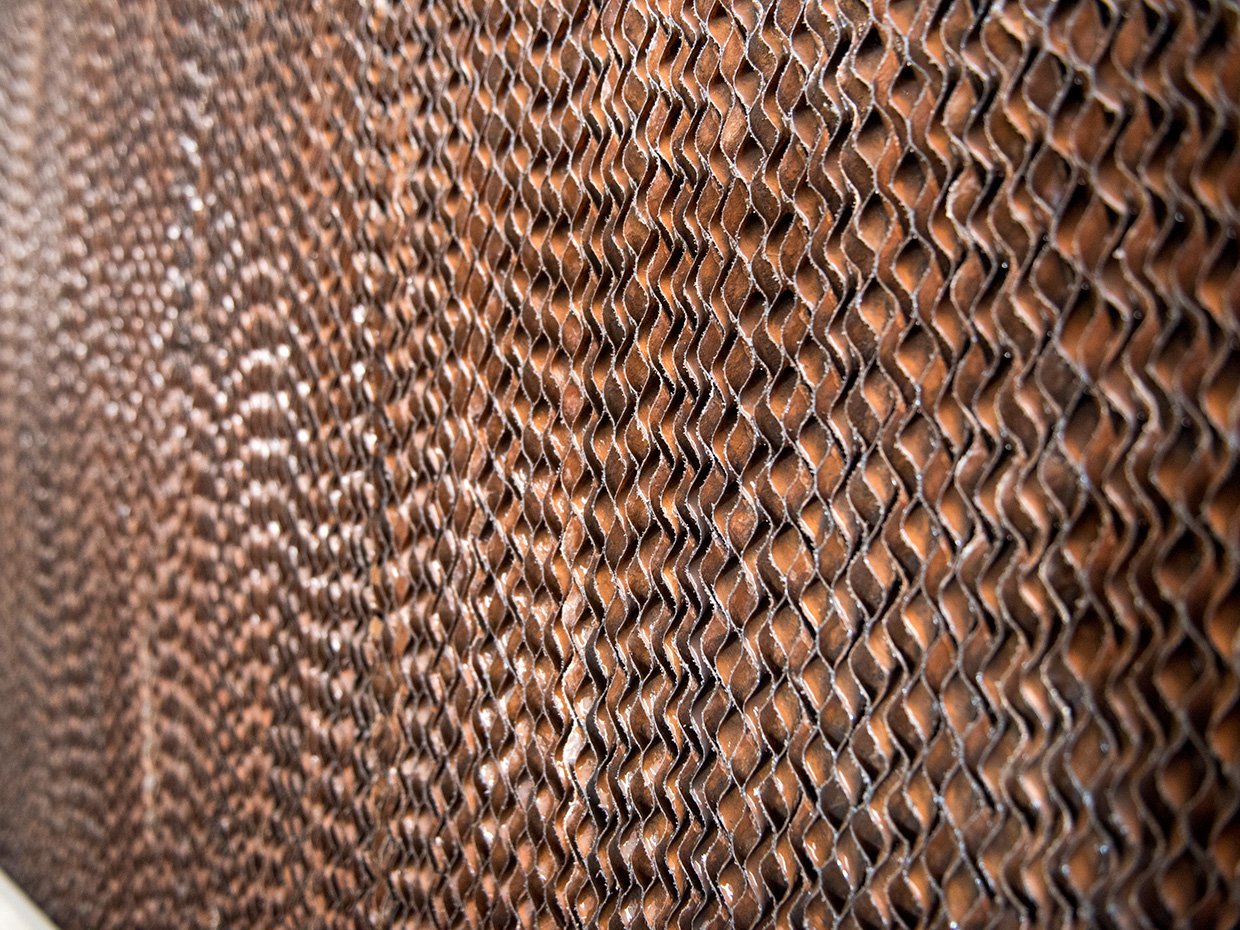

Inside the hangar in Ordos dark, loud and windy. A young man named Zhang turns me in, shouting a stunning noise. “This is the cool side,” he says. Along the wall of the hangar all windows are replaced with desert fans - panels of twisted, tightly packed metal strips poured with water from a pipe from above.

Zhang goes to the door between the two shelves with the equipment, and we pass through it. “This is the hot side,” he says. We stand in an empty, brightly lit room that serves to remove heat. The blown fans of the mining equipment on the other side of the metal wall protrude from small holes, blowing hot air into the room from which another wall leads out of the giant metal fans.

Equipment needs air no warmer than 38 ° C, and Mongolia is not an ideal place for a mining factory. In July, when I went there, a temperature of 40 ° C kept for several days. And in winter, it can drop to –20 ° C, which is why it was necessary to add heat insulation to the hangars. It causes problems and dust, because of which all rooms are fenced with fabric filters.

Windows replaced by desert fans. Metal panels are washed with water from the pipe. When the air enters the room, the water evaporates and cools it.

To save on cooling, some miners choose cooler climatic conditions. BitFury has three large mining factories, one of which is located in Iceland, taking advantage of the cool climate. “Many data centers in the world spend 30-40% of their money when paying for electricity for cooling,” explains Valery Vavilov, director of BitFury. "For our Icelandic data center, this is not a problem."

Two other BitFury factories are located in Tbilisi, Georgia, where the weather is much warmer. According to Vavilov, the company developed a two-phase immersion cooling technology in conjunction with its subsidiary Allied Control. The system immerses the equipment in Novec dielectric heat-conducting fluid, which cools the computers during evaporation. This system is implemented in Georgian data centers.

Industrial fans blow hot air out. On this side, the temperature exceeds 40 ° C.

And although the heat in Ordos is a problem, electricity is very cheap here - only 4 US cents per kWh [ about 2.4 rubles - approx. trans. ], thanks to government subsidies. This is about five times less than the average cost of energy in Britain [the average cost of electricity for the population in Russia is 3.1 rubles. per kW ∙ h // approx. trans. ]. The remaining expenses go only to the computers themselves and the salary of several dozen people who support them in working condition.

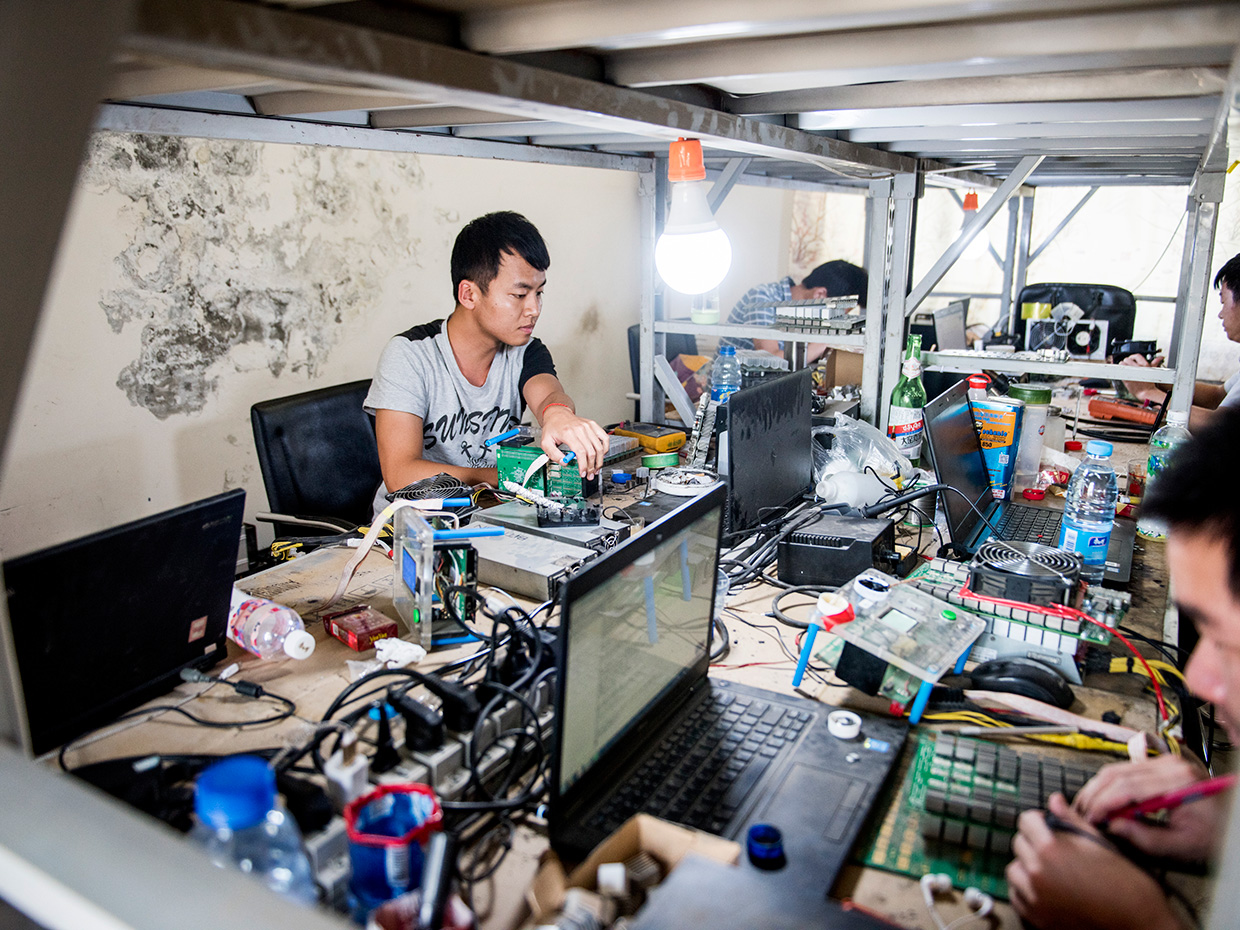

One of them is Zhang. He recently graduated from college in Inner Mongolia and began working in a factory just a few months ago. He calls himself a technical worker, and points to a man standing on a pneumatic elevator, and taking equipment out of racks. “This is what I’m doing,” he tells me.

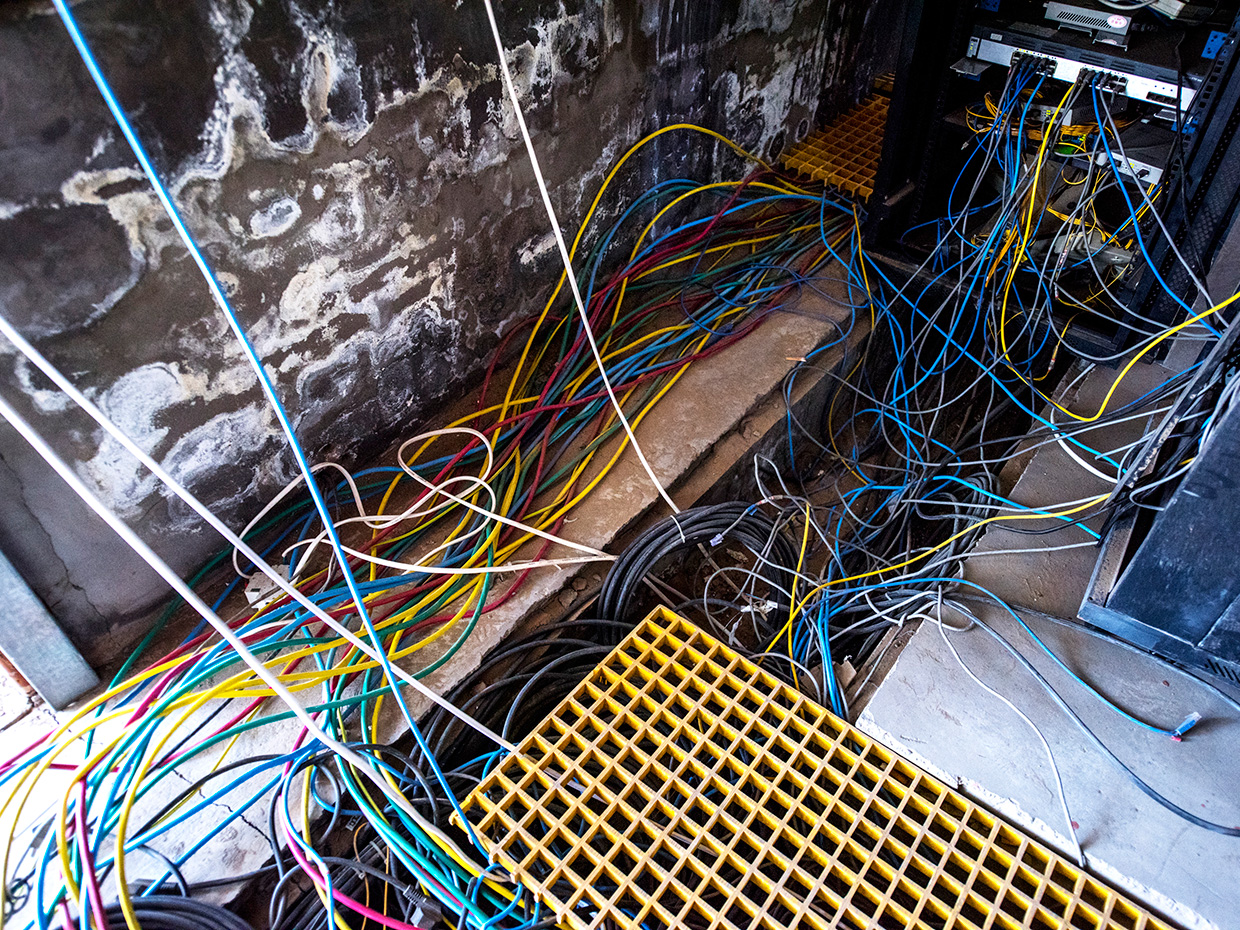

On the control panel S9 there is a red light that turns off when problems occur. Technicians like Zhang are looking for defective equipment in the racks. Finding it, they take it out and send it to a special building on the factory’s territory, where other technicians identify the problem, fix it and return the computer. Sometimes the chip fails. Sometimes a fan burns. In more serious cases, the computer is sent to the Bitmain laboratory in Shenzhen in southeast China. Every second, when the computer is not working - this is a lost profit.

Given the cost of Bitcoin at the time of my visit to Ordos, each computer of the factory earned $ 10 a day. With this speed, the entire factory, which contains more than 20,000 Antminer computers, can yield a profit of $ 70 million per year. And this is just one of the Bitmain factories.

Heat shields. Racks with computers are located on the cold side of the hangar, and fans blow hot air to the hot side.

Due to the bitcoin volatility, it is impossible to predict the annual profit of a mining farm. While I was flying from China back to the US, the cost of Bitcoin dropped by 25%, from $ 2,400 to $ 1,800. As a result, all the factory I visited began to give $ 50,000 less per day. For a week, prices have returned, and are approaching a record.

Price fluctuations, which are familiar to the Bitcoin network from the date of its appearance eight years ago, burden miners with risks and uncertainty. This burden is shared with chip makers, especially those like Bitmain, who invest time and money in development from scratch. According to Nishant Sharma, bitmain's international marketing manager, when the value of the bitcoins this spring took records, the S9 sales doubled. But the company cannot bet on this trend.

Therefore, Bitmain took up diversification. In addition to bitcoin business, the company began to work with artificial intelligence, and is developing equipment for face recognition, which plans to sell to the Chinese government.

Their ASIC competitor, BitFury, is also in search of non-mining industries. “In 2011, we opened a company specifically for mining, but since then it has expanded significantly,” says Vavilov. Among other things, BitFury sells immersion cooling technology to high-performance data centers that are not busy working with bitcoins.

Something is wrong. Software that monitors the work of thousands of miners, informs employees about their failures.

For director Bitmain Jihan Wu, the search for new sources of profit is a way to protect the place occupied by the company on the Bitcoin network, which he describes with tenderness. “For me, the success of Bitcoin was a personal aspiration,” says Wu. - But the company can not be based on the success of Bitcoin. We can't afford it. ”

Uncertainty can explain the fact that the giants of the semiconductor industry still have not entered into a fight. But if the cost of bitcoins remains high, this may change.

“In favor of Bitmain says that they were able to repulse their competitors. But you have not yet seen how Nvidia or Intel are in this sector, and it would be interesting to see what would have happened in this case, ”says Garyk Hilman, economic historian from the London School of Economics, who, together with the University of Cambridge, reviewed the miners.

In the same building on the territory of the factory there is a canteen, a working office, a repair shop and a hostel. Many of the workers have recently graduated from a local university.

And what does a competitor need to get into a fight? He should want to invest a lot of money. In the development of the chip, you can enter several million dollars before the production of the first prototype. "To pull the trigger and pay for all this, we need the will," says Hanke. But he is confident that this will happen. "People will see profits and come."

It may already be working. In September 2017, GMO Internet Group, a Japanese company with a yield of $ 1.2 billion, announced the development of its own ASIC using 7nm technology.

Such an event will be good news for many members of the community who believe that Bitmain’s overly strong position in the mining equipment market threatens Bitcoin.

In the spring, Bitmain caused unrest when developers found the “back door” Antbleed in the S9 Antminer firmware. It could be used to track the location of machines and remote disconnection. While no buyer would find such a vulnerability acceptable, this was particularly bad news for Bitcoin.

The bitcoin protocol was designed to encourage the distribution of hashing powers between miners, not their concentration. Miners have power not only over adding transactions to the Bitcoin network, but also over the evolution of the Bitcoin software itself. After the appearance of the protocol updates, it is the miners who monitor their implementation. If miners unite and decide not to implement an update from major developers, they can delay transactions or even split the currency into competing versions.

Using the back door can give the ASIC manufacturer the ability to plug miners that support the version of the protocol with which the manufacturer does not agree. For example, Bitmain could, by pressing a button, close the entire factory in Ordos, if it had not agreed on any issue with the shareholders.

Wu claims that Antbleed, which has already been fixed, was just a rudimentary code, left by mistake when programmers tried to make a remote switch for use by the equipment owner. This explanation was taken skeptically, but since the S9 firmware is open source, users are sure about the fixed version. Still, this discovery was a clear reminder of the need for diversification in the mining equipment industry.

“Iron makers can seriously control Bitcoin,” says Peter Todd, one of the major Bitcoin developers and consultant in applied cryptography. "A well-designed backdoor would be very difficult to detect, and it could work as a hashing capacity switch, which would kill the network or subdue it to one player."

In July, when Wu was in his office, he thought that there was enough competition in this area, or at least there was enough competition in it for Bitmain to play fair.

“In any area there will still be one or two players. This is the specificity of the ASIC business. If not us, it could be AMD. This may be Nvidia. This may be Intel. It could be someone else, Wu says. “And if we do something wrong, another may come to our place.”

All Articles