A new industrial revolution goes unnoticed

Looking back centuries ago, you can see how the world was changing rapidly. Half a century there, half a century here and now the first industrial revolution has flown by! And then the second. But for contemporaries, everything happened slowly, several generations changed and it was not easy to assess the turning point. Perhaps in a few decades someone will adequately point out another industrial revolution that took place in the twentieth or twenty-first century.

In general, attempts to guess a set of technologies that will lead to the fourth industrial revolution abound. At various times, they relied on nanotechnology, 3D printers, renewable energy, the Internet of things. Something gave the result, something not very, something will probably give in the future. But to guess the specific future magic technology is not so important, since the industrial revolution, in my opinion, is already underway.

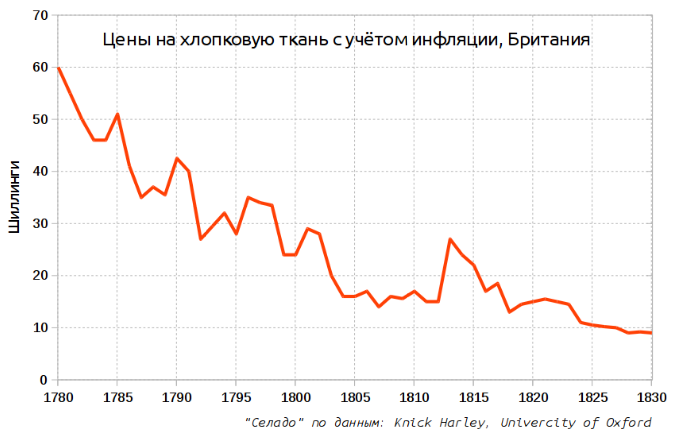

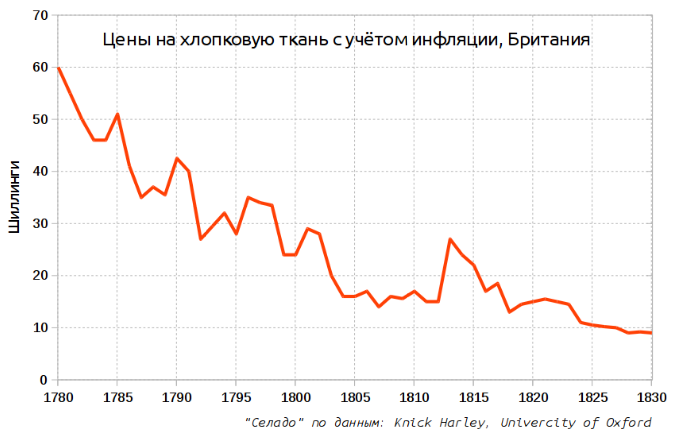

What does the industrial revolution look like from the first, most beloved and classic example? You can look through the eyes of an engineer and describe it through the development of steam engines and a loom, but if you try to look through the eyes of an economist in search of “forest for trees”, first of all it is a massive price reduction and distribution of goods affecting a significant part of society. Both old and new industries. For example, in the birthplace of the industrial revolution in Britain, the main driver was the textile industry, leading in terms of employment and value added. Thanks to the mechanization of cotton processing, textile production has skyrocketed and prices have fallen. Against the background of weaving centuries, this happened instantly (a revolution!), But in practice it dragged on for decades. On the example of cotton fabric:

Cotton fabric prices declined annually by 4% and, as a result, products became much more affordable for the public. Similar events occurred in other industries. From now on, a worker could supply several times more people with goods than before.

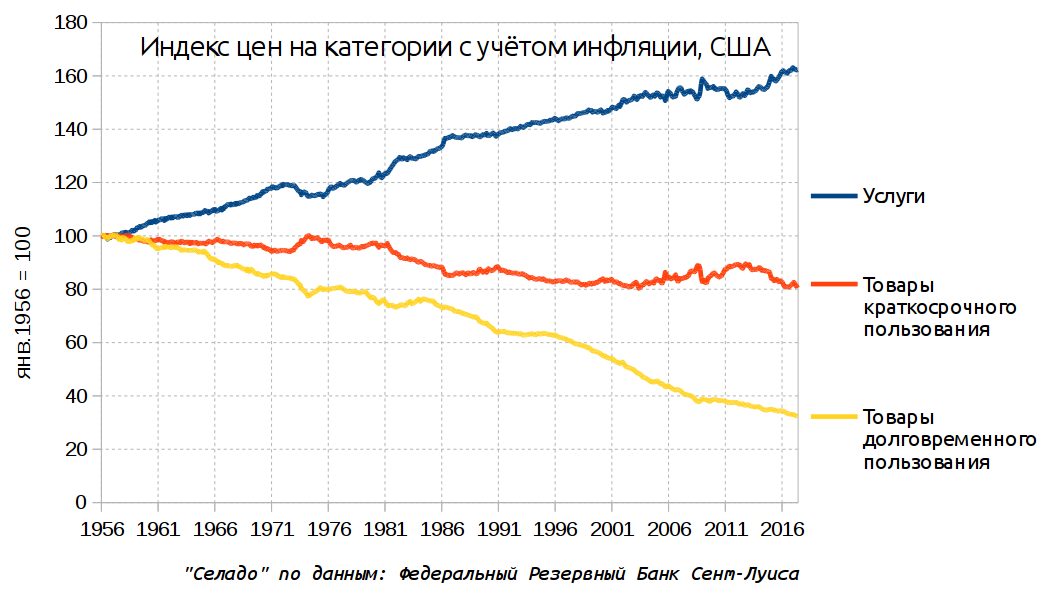

As I already showed in one of the previous articles, the introduction of industrial innovations is still taking place decades, at least two centuries ago, even now - electric cars, renewable energy, and so on. Therefore, look for traces of the industrial revolution should be on a similar time scale. Secondly, in order not to get bogged down in the “trees”, I will again leave thoughts about concrete innovations behind the board and look for traces of a hypothetical revolution. Unfortunately, the long statistical lines for decades are available only for the United States, so examples will be based on their statistics:

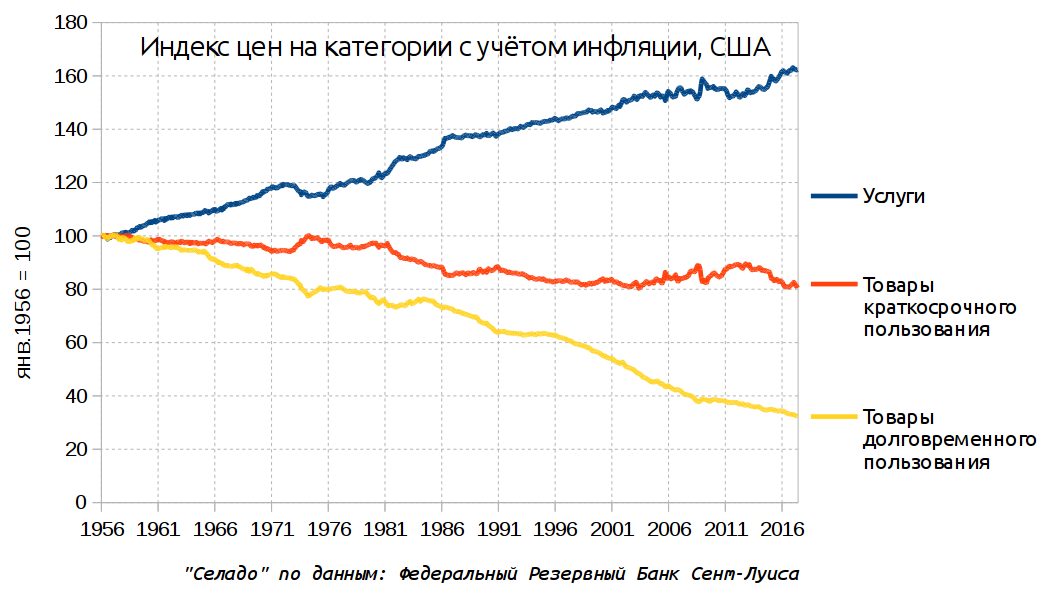

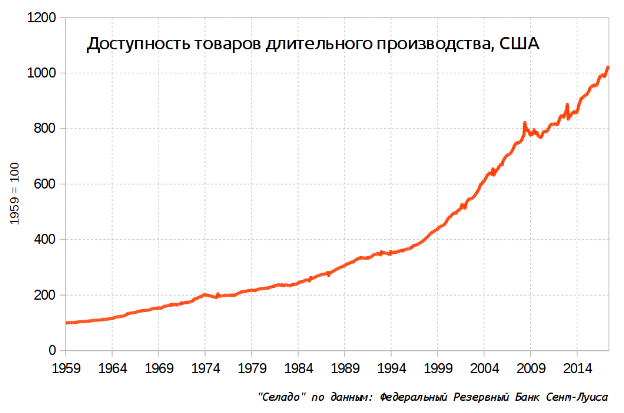

There are two very obvious trends: while prices for services are rising faster than inflation, prices for durable goods have fallen three times. Machines, household appliances, electronics, furniture, technical equipment, etc. - all this is getting cheaper, something else is faster, something is slower. Non-durable goods (food, clothing, fuel, household chemicals, stationery, etc.) almost did not change in price, as they strongly depend on volatile prices for energy and raw materials. In the domestic economy, the effects discussed are less noticeable due to crises, but in general this trend is fair for the whole world.

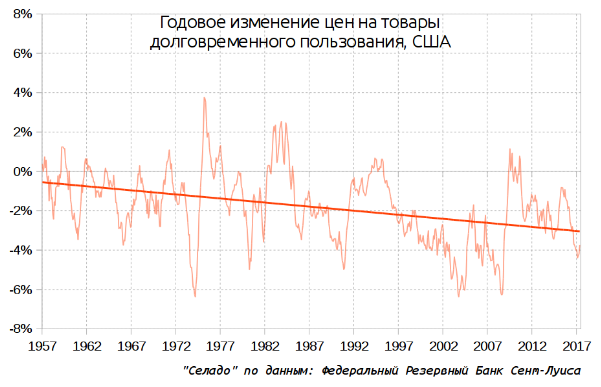

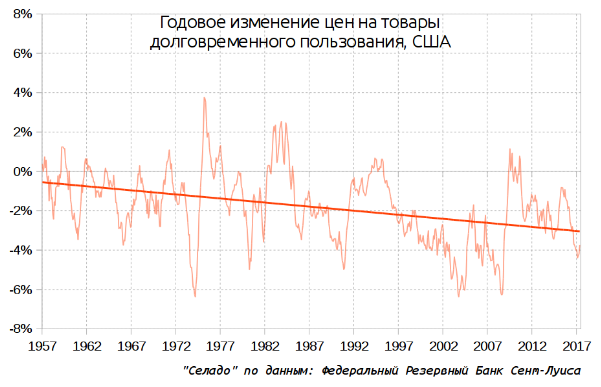

In this case, the schedule does not reveal the whole situation. The prices of goods are not only declining, the process is accelerating and since 2000, goods have become cheaper by 2-6% annually. The crisis of 2008–2009 slowed down development due to lower investment in labor productivity, but now prices are again falling by 4% per year, as during the first industrial revolution:

The bold line indicates a linear trend.

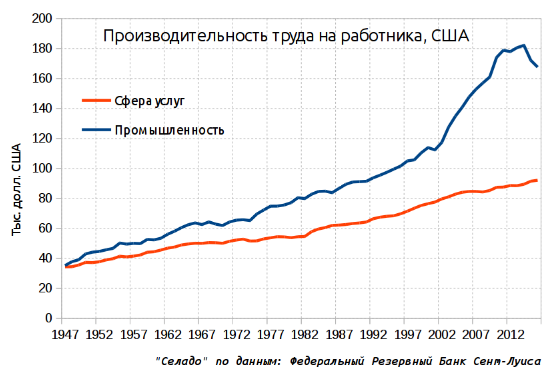

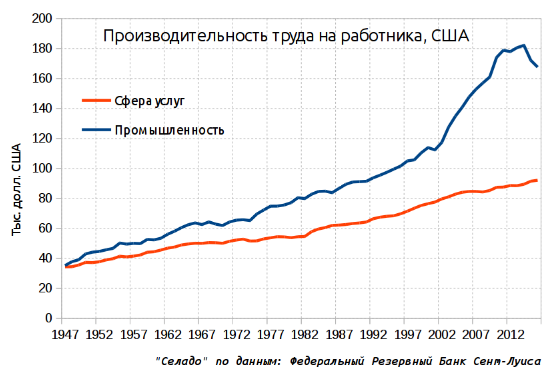

Strictly speaking, something revolutionary in production does not necessarily follow from such a decline, for this may be due to other factors. In order for the price reduction to relate to the topic under discussion, it was, as we found out above, that there should be a substantial increase in labor productivity and statistics rather confirm this:

Taking into account the growth of incomes of the population around the world, modern people literally bathe in cheap products compared to the previous generation. But why does life still seem very complicated and expensive?

An interesting and not for all obvious point is that the growth of labor productivity in some industry reduces the share of this industry in the economy and in human life in particular. When an industry becomes highly efficient, there is no need for millions of workers. People move to work in less and less vital areas, to which the attention of society is shifting. There are already two such transitions: from food production to the production of goods (industrialization) and from goods to services (post-industrialization).

Before the industrial revolution, the whole existence of man revolved around food and the bulk of society were peasants who provided themselves and society with their daily bread. A small proportion of society worked to provide the peasants with the goods they needed. But when agriculture became efficient, such a huge number of farmers turned out to be unnecessary. Food prices fell, the availability and variety of diets increased and the problem of nutrition faded into the background. The freed working hands went to the industry, where they created new products, making life more comfortable. This new stratum of the economy has become much more agricultural, but initially it was ineffective and could not attract attention.

A similar process has been going on since the second half of the twentieth century: the industry is becoming more and more efficient, the number of workers there is constantly falling, goods are becoming cheaper, and they begin to play an ever smaller role in people's lives. A complete house of equipment and gadgets is available to almost anyone, and this is no longer a success status. Parallel to this process, the developing service sector is drawing in a mass of people who are simply not needed in industry. The service sector creates a previously inaccessible level of comfort for a resident of the industrial world, it is much less efficient than industry, therefore its goods are labor intensive and expensive. But at the same time they are new items of desire and status. The described is clearly seen on this graph:

Food needs are met by a thin yellow strip of “peasants”, in addition to the USA, the world's largest exporter of agricultural products. The industry is a bit more complicated, but with adjustments for imports and labor productivity, it can be said that the demand for goods is satisfied by 80% of the local labor force, almost entirely. In the past decade, labor productivity in industry has grown and is so high that even in China, most of the employment and value added are in the service sector, and industry has receded into the background.

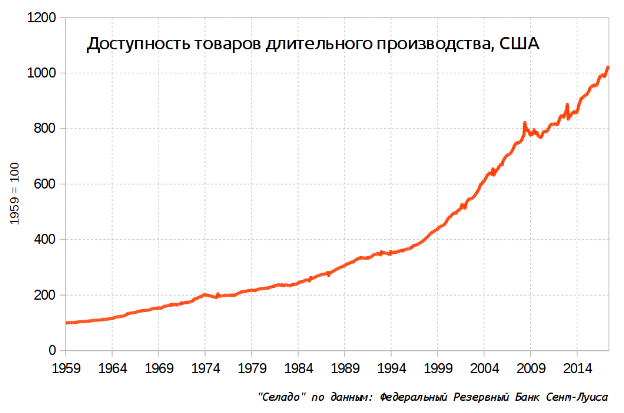

It is also interesting to add a factor of income growth, although this already lies outside the plane of the industrial revolution. Salaries are rising, prices are falling and with a correction for real disposable income, the situation has improved already 10 times:

In a sense, the situation tends to “communism” and soon, thanks to scientific and technological progress and economic growth, the goods will be almost free =)

In general, attempts to guess a set of technologies that will lead to the fourth industrial revolution abound. At various times, they relied on nanotechnology, 3D printers, renewable energy, the Internet of things. Something gave the result, something not very, something will probably give in the future. But to guess the specific future magic technology is not so important, since the industrial revolution, in my opinion, is already underway.

What does the industrial revolution look like from the first, most beloved and classic example? You can look through the eyes of an engineer and describe it through the development of steam engines and a loom, but if you try to look through the eyes of an economist in search of “forest for trees”, first of all it is a massive price reduction and distribution of goods affecting a significant part of society. Both old and new industries. For example, in the birthplace of the industrial revolution in Britain, the main driver was the textile industry, leading in terms of employment and value added. Thanks to the mechanization of cotton processing, textile production has skyrocketed and prices have fallen. Against the background of weaving centuries, this happened instantly (a revolution!), But in practice it dragged on for decades. On the example of cotton fabric:

Cotton fabric prices declined annually by 4% and, as a result, products became much more affordable for the public. Similar events occurred in other industries. From now on, a worker could supply several times more people with goods than before.

In search of traces of revolution

As I already showed in one of the previous articles, the introduction of industrial innovations is still taking place decades, at least two centuries ago, even now - electric cars, renewable energy, and so on. Therefore, look for traces of the industrial revolution should be on a similar time scale. Secondly, in order not to get bogged down in the “trees”, I will again leave thoughts about concrete innovations behind the board and look for traces of a hypothetical revolution. Unfortunately, the long statistical lines for decades are available only for the United States, so examples will be based on their statistics:

There are two very obvious trends: while prices for services are rising faster than inflation, prices for durable goods have fallen three times. Machines, household appliances, electronics, furniture, technical equipment, etc. - all this is getting cheaper, something else is faster, something is slower. Non-durable goods (food, clothing, fuel, household chemicals, stationery, etc.) almost did not change in price, as they strongly depend on volatile prices for energy and raw materials. In the domestic economy, the effects discussed are less noticeable due to crises, but in general this trend is fair for the whole world.

In this case, the schedule does not reveal the whole situation. The prices of goods are not only declining, the process is accelerating and since 2000, goods have become cheaper by 2-6% annually. The crisis of 2008–2009 slowed down development due to lower investment in labor productivity, but now prices are again falling by 4% per year, as during the first industrial revolution:

The bold line indicates a linear trend.

Strictly speaking, something revolutionary in production does not necessarily follow from such a decline, for this may be due to other factors. In order for the price reduction to relate to the topic under discussion, it was, as we found out above, that there should be a substantial increase in labor productivity and statistics rather confirm this:

Taking into account the growth of incomes of the population around the world, modern people literally bathe in cheap products compared to the previous generation. But why does life still seem very complicated and expensive?

Productivity growth leads to oblivion of the industry

An interesting and not for all obvious point is that the growth of labor productivity in some industry reduces the share of this industry in the economy and in human life in particular. When an industry becomes highly efficient, there is no need for millions of workers. People move to work in less and less vital areas, to which the attention of society is shifting. There are already two such transitions: from food production to the production of goods (industrialization) and from goods to services (post-industrialization).

Before the industrial revolution, the whole existence of man revolved around food and the bulk of society were peasants who provided themselves and society with their daily bread. A small proportion of society worked to provide the peasants with the goods they needed. But when agriculture became efficient, such a huge number of farmers turned out to be unnecessary. Food prices fell, the availability and variety of diets increased and the problem of nutrition faded into the background. The freed working hands went to the industry, where they created new products, making life more comfortable. This new stratum of the economy has become much more agricultural, but initially it was ineffective and could not attract attention.

A similar process has been going on since the second half of the twentieth century: the industry is becoming more and more efficient, the number of workers there is constantly falling, goods are becoming cheaper, and they begin to play an ever smaller role in people's lives. A complete house of equipment and gadgets is available to almost anyone, and this is no longer a success status. Parallel to this process, the developing service sector is drawing in a mass of people who are simply not needed in industry. The service sector creates a previously inaccessible level of comfort for a resident of the industrial world, it is much less efficient than industry, therefore its goods are labor intensive and expensive. But at the same time they are new items of desire and status. The described is clearly seen on this graph:

Food needs are met by a thin yellow strip of “peasants”, in addition to the USA, the world's largest exporter of agricultural products. The industry is a bit more complicated, but with adjustments for imports and labor productivity, it can be said that the demand for goods is satisfied by 80% of the local labor force, almost entirely. In the past decade, labor productivity in industry has grown and is so high that even in China, most of the employment and value added are in the service sector, and industry has receded into the background.

Commodity “communism”

It is also interesting to add a factor of income growth, although this already lies outside the plane of the industrial revolution. Salaries are rising, prices are falling and with a correction for real disposable income, the situation has improved already 10 times:

In a sense, the situation tends to “communism” and soon, thanks to scientific and technological progress and economic growth, the goods will be almost free =)

All Articles