IBM PC: full story, part 1

Bill Gates, mysterious death, IBM, behaving like a smart startup. This story has it all!

Ibm 5001 laptop

It can be stated that the IBM PC was not the first PC from IBM. In September 1975, the company introduced the IBM 5100, the first “portable” computer (this meant that it weighed only 25 kg, and for him it was possible to buy a special suitcase for travel).

The 5100 was not technically a microcomputer — it used an IBM-designed PALM processor spread over the entire motherboard, and not contained in a single microchip. But from the point of view of the end user, the difference was small - it clearly fit the definition of a personal computer. It was a self-sufficient, Turing-complete, programmable machine no larger than a suitcase, with a tape drive for loading and saving programs, a keyboard, a 5 "screen and 16 KB of memory.

5100 differed from the first wave of the PC price and advertised scope. The price started at $ 10,000 and could easily climb up to the $ 20,000 mark. IBM promoted the machine as a serious tool for field engineers in remote locations that do not have access to large IBM machines, rather than a device for entertainment, training, hacking or office work.

IBM 5110, small upgrade 5100

Advertising has changed with two following concept iterations, models 5110 and 5120, which advertised as systems suitable for the office, with an accounting application, a database, and even a word processor. But prices remained at a high level, despite the fact that for real office work, this computer needed to be connected to a standalone array of disks larger than the computer itself, with the result that the whole system became more like a minicomputer than a PC.

System / 23 Datamaster and University Students

However, it turns out that although the IBM PC was never named with the full name, it was officially the IBM PC 5150 model (not to be confused with the Van Halen album ) - a continuation of the 5100 notebook line, rather than something completely new, despite the fact that its architecture did not have nothing to do with predecessors.

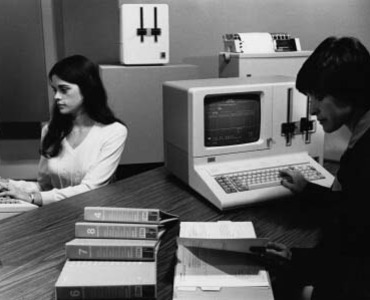

In February 1978, IBM began work on the first microcomputer - and this again was not an IBM PC. It was a System / 23 Datamaster machine.

The System / 23 Datamaster

It was again designed for office work, and built on an Intel 8085 microprocessor. It was large and heavy (43 kg) and cost about $ 10,000, which, coupled with its business orientation and dry usage, radically distinguished it from computers like Apple II . But technically it was a microcomputer. IBM was a huge company with legendary tangled bureaucracy, which meant that projects sometimes took an incredibly long time to complete. Despite the fact that the Datamaster project was ahead of the PC by two years, it did not go out until July 1981, just in time for his glory to be eclipsed by the announcement of the release of the IBM PC next month. And yet, if a question about the first microcomputer from IBM emerges in the game of erudition, then here is the answer.

Atari VCS (2600), which, oddly enough, is related to the origins of the IBM PC

Now the story begins for real

The machine, which will become known as a real IBM PC, suddenly takes its origin in Atari. Apparently, having felt the taste of success in the wake of the explosion of video games organized by the Space Invaders game and the Atari VCS prefix, as well as the release of their own PCs, the Atari 400 and 800 , the company in July 1980 proposed to the chairman of the board of IBM, Frank Carey: if IBM wants to make its PC , Atari can condescend to the development of such for it.

Carey was not such a limited lover of mainframes, as they try to imagine. He advocated the development of small systems - even if by “small” IBM often understood something completely different than in the rest of the world. Carey brought this offer to IBM's director of input systems, Bill Low, who worked in Boca Raton, Florida. Low presented the proposal to a committee of governors who declared him "the dumbest thing they had ever heard." And indeed, IBM and Atari make up the strangest pair. But at the same time, everyone understood that Lowe speaks at the personal request of the chairman of the board, and such proposals simply do not dismiss, if you, of course, care about your career. So they ordered Lowe to put together a team to make a detailed proposal for how IBM could make a PC on its own, and submit it in a month.

IBM PC 5150 with printer, introduced in August 1981

Low assembled a team of 12 or 13 people (sources differ on the exact figure) to create a draft proposal. Breaking the tradition of the company, he did not specifically begin to assemble a large team and introduce a formal management structure, hoping to create some kind of “hacker magic”, which gave rise to the PC. His project manager, Don Estridge, said: "If you are competing with people starting in the garage, you need to start in the garage."

One might have expected that such a computer industry goliath, like IBM, would make its way into the PC market without a hitch. Although PC lovers were proud of the fact that they built a new market with bold decisions, creativity and flexibility that a phlegmatic giant like IBM is not capable of, they were still afraid of this development. However, IBM decided to be a good boy, get acquainted with the existing state of affairs and talk with the people who created the PC market in order to understand what is needed and where the theoretical IBM PC could fit in.

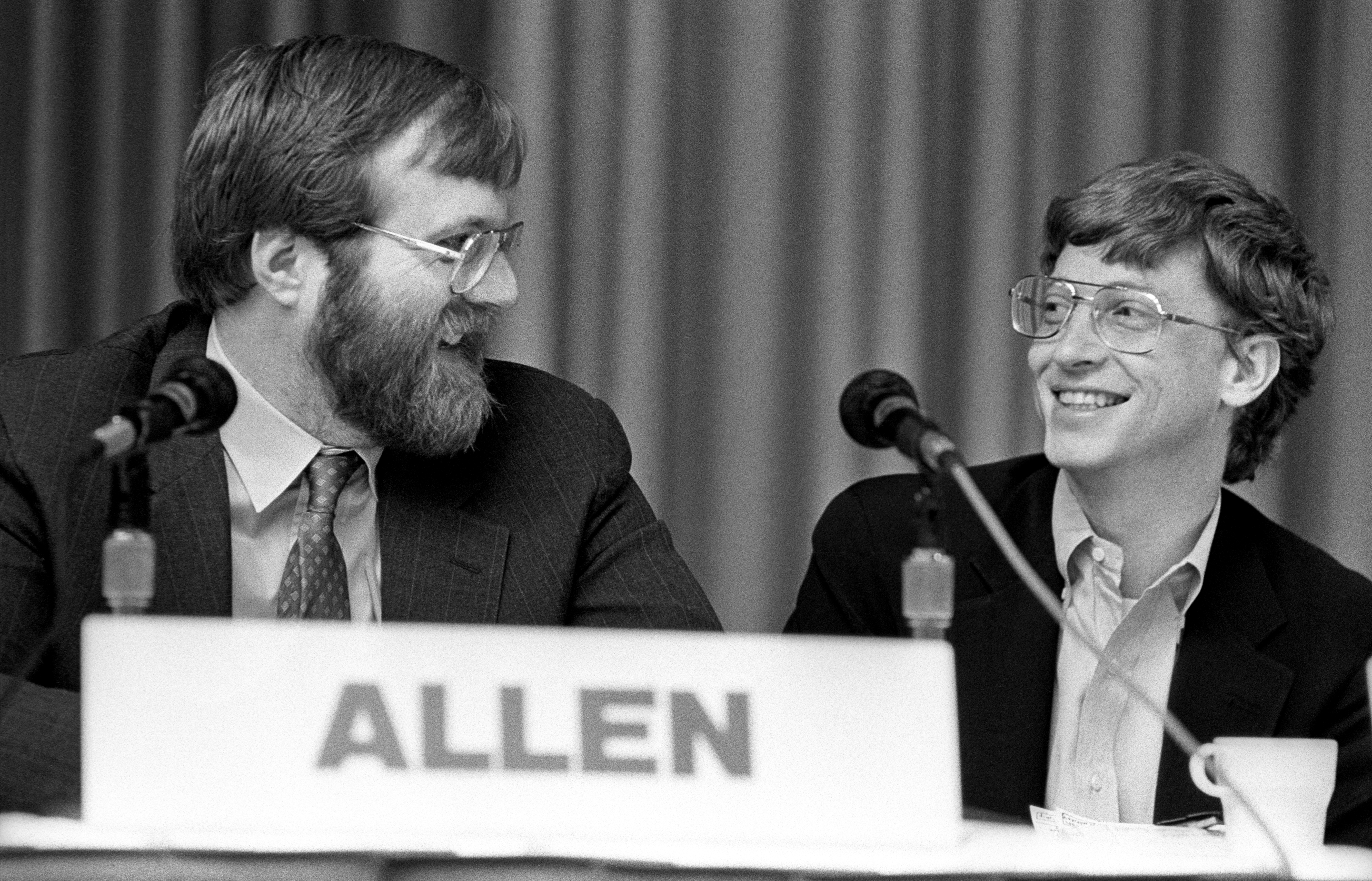

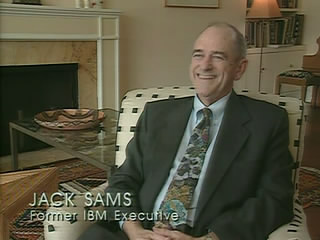

Thinking this way, Jack Samms, head of software development, recommended talking to Microsoft. Sams was unusually well acquainted with the PC market for an IBM employee; He agitated the company to buy from Microsoft BASIC for Datamaster, but his proposal was rejected in favor of internal development. “It just took longer and cost more,” he said later. Sams called Bill Gates on July 21, 1980 and asked if he could come to the Seattle office the next day and have a friendly chat about the PC. “But we shouldn’t be particularly happy and do not expect anything supernatural,” he said.

This is Bill Gates in 1984 at the age of 29. Imagine how young he looked 4 years before.

Gates and Steve Ballmer, his right hand and the only one among the company of hackers with a business education owner, yet realized that the situation could promise something supernatural. When Sams arrived with two employees acting as witnesses, Gates personally went out to meet them. (Sams initially thought that Gates, with his face, voice and figure resembling a 12-year-old boy, was some kind of messenger). Sams immediately pulled out a non-disclosure agreement, which was a standard procedure for IBM.

“IBM didn't make things easier,” Gates recalled later. - It was necessary to sign all these strange agreements, which said that IBM can do what it wants and when it wants, and use your secrets at its own discretion. So it took a little trust. ” However, he immediately signed them.

Sams wanted to know the general state of the PC market from Gates, who was intimately familiar with this topic. So Gates was just one of the prominent figures with whom he spoke. However, he also had a hidden motive: to see what Gates was doing, to try to understand whether Microsoft could be a useful resource for him. He was very impressed.

After consulting with Gates and the others, Lowe submitted a proposal on 8 August about the machine that IBM needed to build. From many popular historical sources, for example, from the old Triumph of the Nerds documentary, it seems that the IBM PC was quickly dazzled in an unrealistic rush. In reality, this development was very seriously reflected. She had two very interesting aspects.

Modest MOS 6502

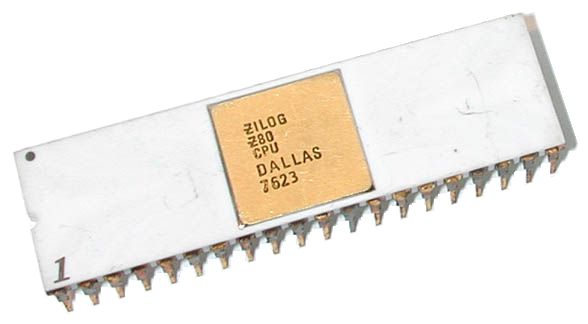

The same modest Zilog Z80

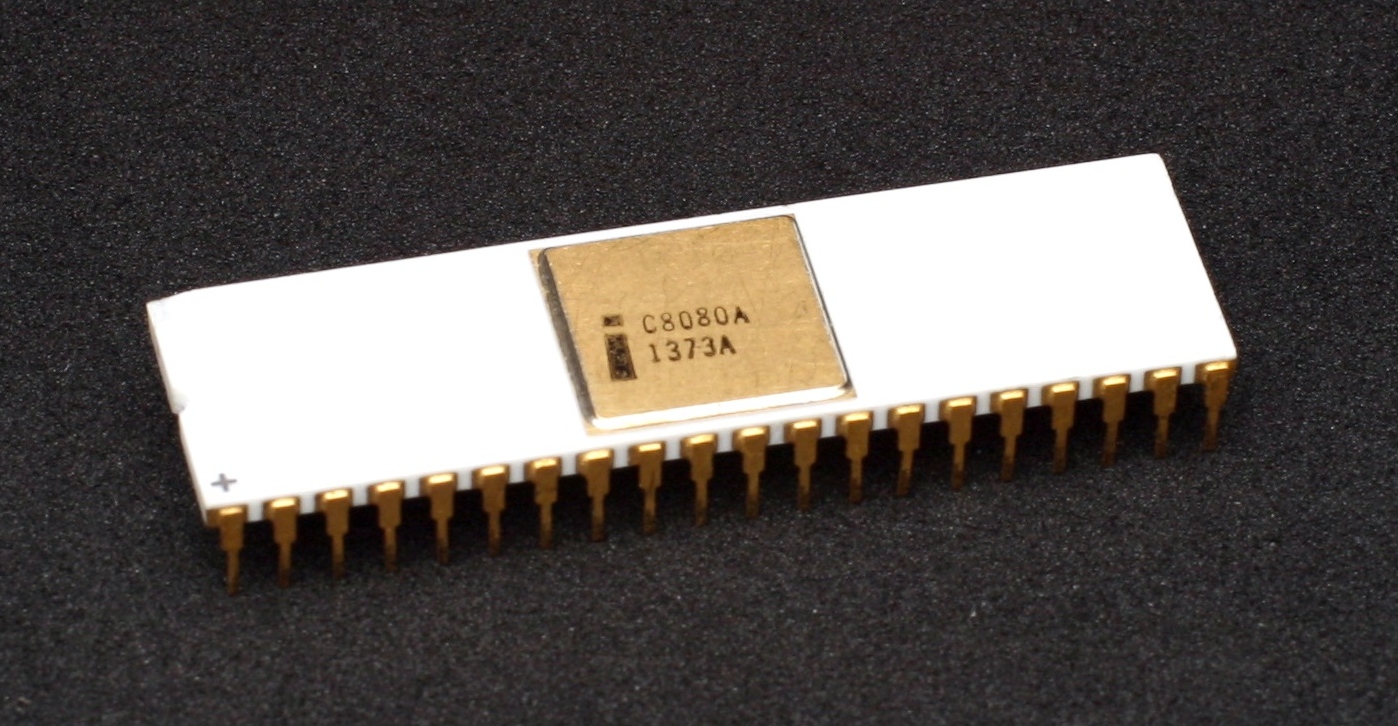

Intel 8080 compatible with Z80

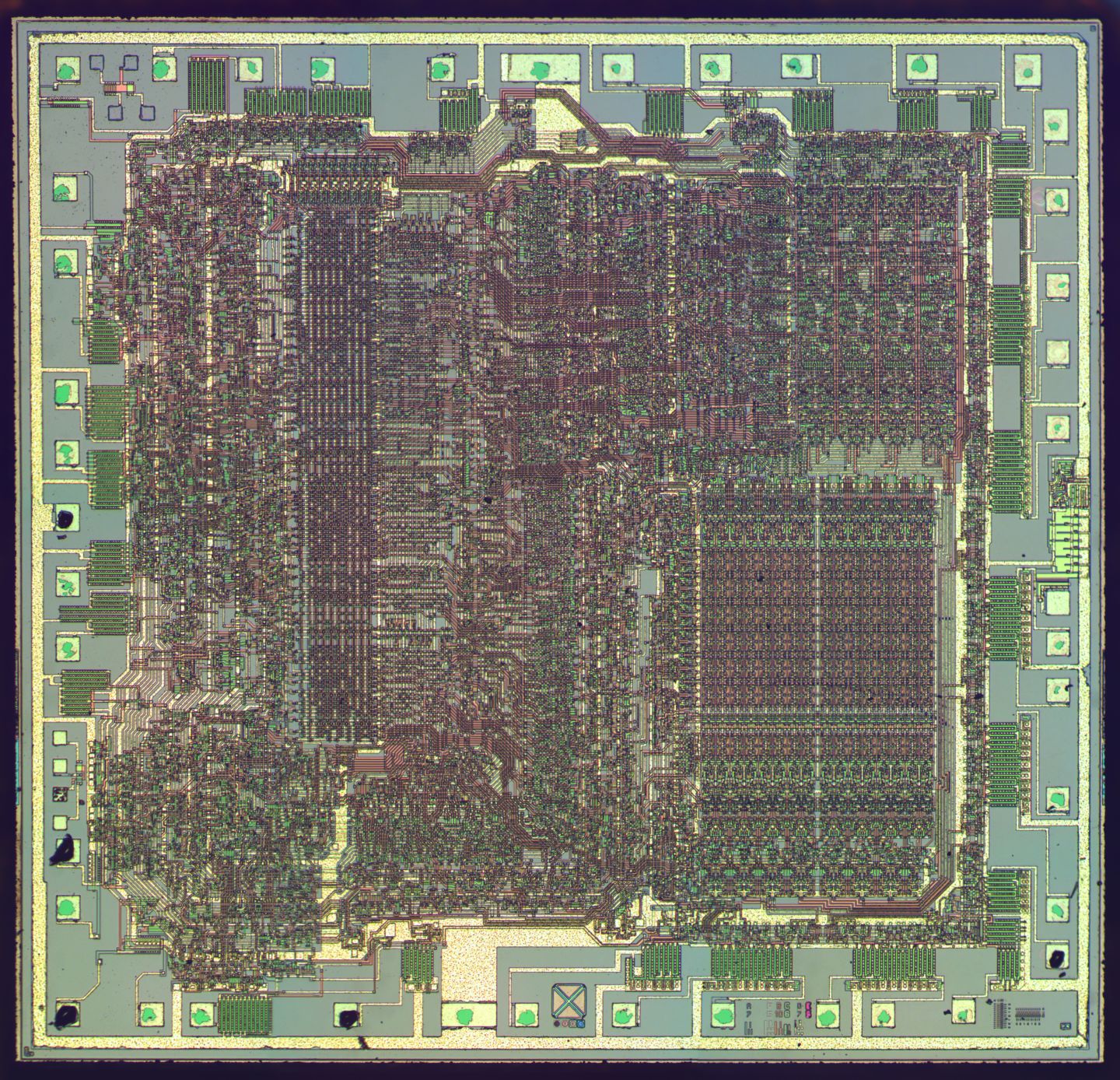

Integrated circuit clone Z80

Open architecture

At that time, almost all PCs used one of two processors — either MOS 6502 or Zilog Z80. Both of them appeared in relatively small start-up companies, and each of them borrowed the main instruction set and most of the circuit from another, more expensive CPU, produced by a large company - from Motorola 6800 and Intel 8080, respectively. (If we talk about the ethical side of the matter, then both processors were mainly developed by engineers, who also worked on the creation of processors that served as “inspiration” for them).

Both were 8-bit chips with memory addressing up to 64 KB. And it already became a problem. Apple II was limited to 48 KB of RAM due to the need to address 16 KB of ROM. And even where these restrictions were not yet a problem, it became clear that problems would soon appear.

So the team decided to work on a next-generation CPU that could leave these limitations in the past. IBM collaborated with Intel for a long time, so I chose Intel 8088, a 8-bit / 16-bit hybrid CPU capable of operating at 5 MHz (much faster than the 6502 or Z80), and, best of all, it could work with addressing a whole megabyte of memory. The IBM PC will have the opportunity for growth unavailable to its predecessors.

Another interesting aspect is the very popular idea of “open architecture”. In the book "Accidental Empires" [Accidental Empires] and the Triumph of the Nerds movie [Triumph of the Nerds] based on it, Robert Krindzhli argues that this choice was made on the basis of necessity, and this was another symptom of the hasty creation of a machine. “IBM product of the year! What nonsense! To save time, instead of creating it from scratch, they bought ready-made components and assembled a computer from them - something that in the IBM language is called “open architecture”.

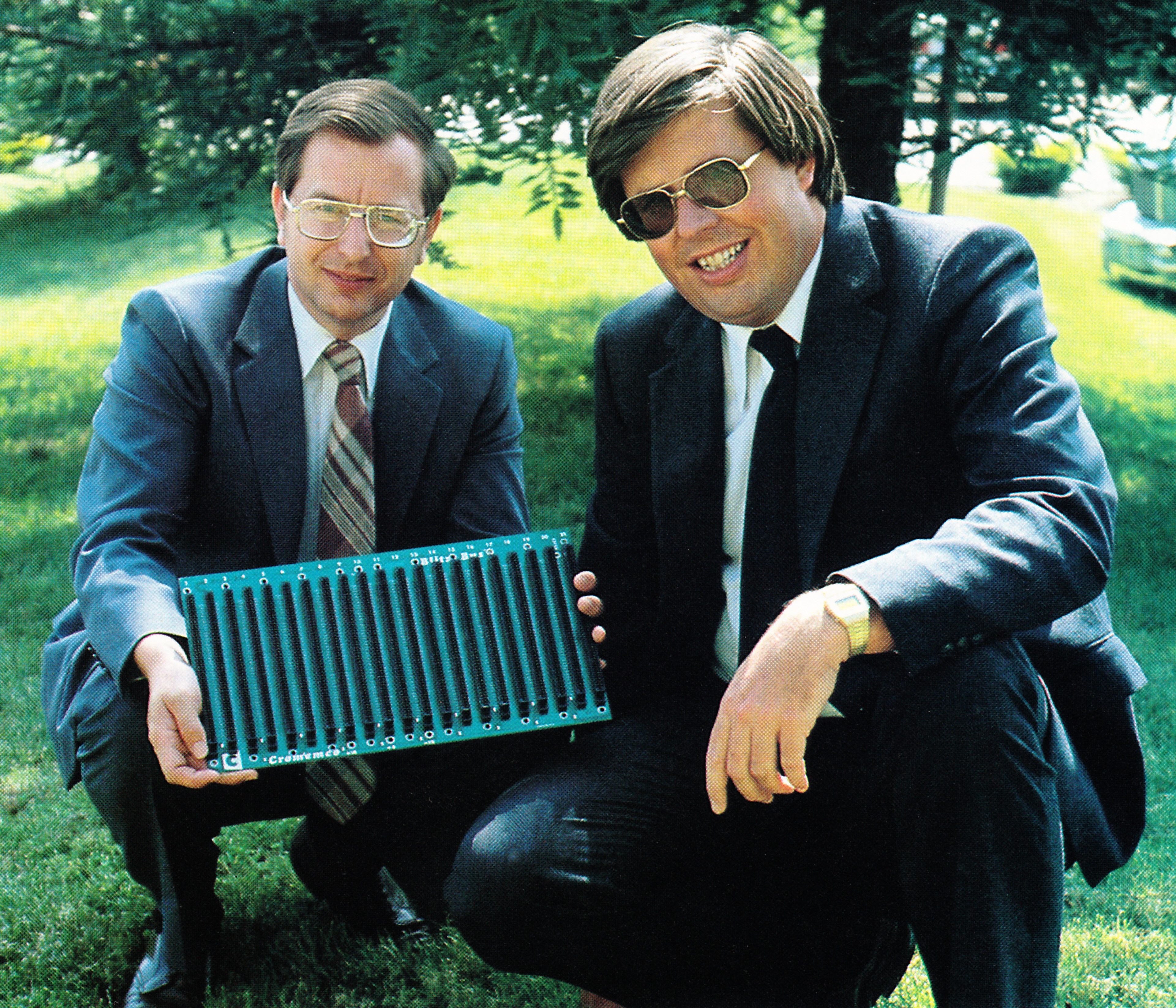

Harry Garland and Roger Melen, co-founders of Cromemco, are holding the S-100 motherboard, 1981

Well, first of all, the “open architecture” can hardly be called the “IBM language”. This is the term that almost everywhere described the IBM PC, and probably the least in the IBM itself. (For example, in this detailed and detailed article for Byte magazine, "Creating an IBM PC", team member David Bradley never uses it). But what do people mean by "open architecture"? Unfortunately for journalists, “openness” or “closeness” of architecture is not a choice of “or / or”, but, like everything else in life, a continuum.

For example, Apple II also had a relatively open architecture. One of the few battles won by Wozniak from Jobs was the inclusion of expansion slots and the publication of a detailed scheme, which allowed users to do something with the machine that its creators could not foresee, and that was one of the reasons for its amazingly long life. The CP / M computers that were often used in enterprises were even more open, because they were based on the generally accepted and well described specifications of the S-100, and had many expansion slots. This allowed them to share both hardware and software.

Commodore PET was released in January 1977 and used the MOS 6502 - one of the chip options that IBM could use in a PC

Instead of talking about open architecture, we better talk about modular architecture. IBM made a computer designer, a set of interchangeable components that a customer could assemble in any combination suitable for his needs and wallet. Immediately after launching, he had a choice between a color video card capable of drawing graphics and games, or a monochrome card capable of producing 80 columns of text characters. It was possible to choose the amount of internal memory in the range from 16 KB to 256 KB, one or two floppy drives or a cassette drive, etc. As a result, when all the third-party companies were involved in this game and IBM expanded the product line, you could simply drown in the options.

Most of the individual components were actually ordered from third-party companies, which dramatically accelerated the development process. The use of proven and well-known components has other advantages, from which emerged the reputation of the IBM PC as a reliable machine.

Tandy Radio Shack TRS-80 using Zilog Z80

Ordering such a large amount of equipment from third-party companies for IBM was a departure from tradition, but in other aspects of the IBM PC continued the company's development philosophy. There was not one, the only one suitable for all the mainframe. When you called and said you wanted to buy one of these monsters, IBM sent a couple of representatives to discuss your needs, financial means, and check the available space. Then you worked together to develop a system that best suits you, deciding how much disk space you need, how much memory and how many cassette drives you need, what printers, terminals, punch card readers, etc. you need.

In this sense, the IBM PC was a continuation of the company's usual work in miniature. Of course, most other personal computers also had some kind of flexibility. However, it is important that IBM decided to put everything on modularity, extensibility, or, if you like, openness. Like the choice of CPU, it gave the car room to grow, as new, improved hard drives, video cards and then sound cards inevitably began to appear. This is the key reason why the architecture developed so long ago remains with us today, in a highly redesigned form.

Apple II using MOS 6502

Looking for an operating system

The committee endorsed Low’s idea of creating a computer. IBM, realizing that its own bureaucracy is an obstacle to people trying to do something, shortly before this, came up with the concept of an “Independent Business Unit, IBU]. The idea was for IBU to work as a semi-independent entity freed from ordinary bureaucracy, and IBM to play the role of a venture capitalist. In the Fortune magazine, IBU was described as “How to start your own company without leaving IBM.” Chairman Carey, whose quotation is often distorted and misunderstood, called the IBU IBM’s answer to the question “How to make an elephant dance tap-dance?” IBU Low would call Project Chess, and the machine being developed Acorn (apparently, nobody knew about the British computer company same name). The team was given a blank check, with one restriction - Acorn was supposed to appear in a year.

Jack Sams, so impressed with Bill Gates and Microsoft, returned to them almost immediately after IBM launched Project Chess on August 21, 1980. Having received from Gates another signed by the NDA, he was ready to finish with theories and speak frankly. He explained that IBM plans to make its own PC, but this did not surprise anyone. Adhering to the accepted philosophy of the machine, which can be customized for any tasks, he planned to offer users a choice - to use the BASIC environment embedded in the ROM, as was the case with Apple II, PET and TRS-80, or boot into the CP / M disk operating system, which was very popular among business users.

Microsoft, as the main supplier of BASICs for microcomputers, was the obvious choice for the first option. She also recently took up other compiled languages like Fortran, and Sams did not mind the presence of other languages. Robert Krinjli and others give too much importance to the fact that IBM turned to third-party software for software (another argument in favor of a quick fix), but this was not something out of the ordinary. Apple, Commodore, Radio Shack and many others did the same by taking BASIC from Microsoft.

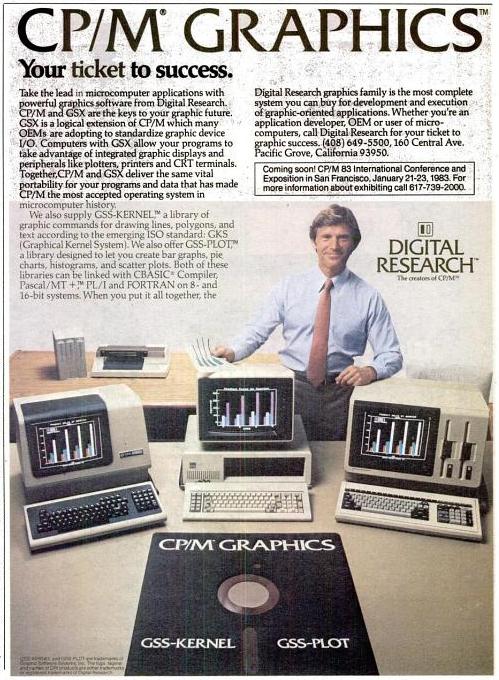

Advertising Package CP / M Graphics from Digital Research

Sams could not figure out something else. That spring, Microsoft introduced its first hardware, the Z80 SoftCard. It was the Z80 CPU on a card plugged into one of the Apple II expansion slots. After installing the card, the user could choose - give control over the machine to the standard CPU 6502 or Z80. On the card, there were schemes that allowed the Z80 to use standard memory and other Apple II peripherals. It was an amazing hack, developed jointly with Seattle Computer Products, a small hardware company that worked closely with Microsoft at the time.

Since CP / M worked only on Z80 processors, Apple II users were cut off from the CP / M business software universe. Now they have access to the best features of both worlds - all the software for education and entertainment, using the capabilities of Apple II graphics (not to mention VisiCalc) and all text-based business applications CP / M. SoftCard was a huge success, not reaching just VisiCalc itself, in the process of promoting Apple II to the American business market as the only machine based on 6502. Apple II with SoftCard soon became the most popular configuration of equipment for CP / M.

Microsoft Z80 SoftCard

Since SoftCard came with a copy of CP / M, Sams was confident that this OS belonged to Microsoft. Gates explained that this is not the case - Microsoft only acquired a license from its owner, Digital Research.

Gates and Gary Kildall , head of Digital Research and one of the first CP / M programmers, have known each other for many years, and have developed mutual respect and some kind of partnership. With the release of the new machine, Microsoft was working on languages, and Digital, on operating systems.

Steve Wood, one of the first Microsoft programmers:

When we communicated with another OEM, a manufacturing client who wanted BASIC or any other product to work on its hardware, by the age of 77-78 we had always tried to persuade them to cooperate with Digital and CP / M, because we were so much easier to work with. When we did something to order, such as the General Electric version or the NCR version, it was a terrible headache. Our life became simpler when someone just bought a license for CP / M and brought it up at home, after which our programs simply worked right away. Gary did the same. If someone approached him for a CP / M license, and they needed languages, he sent people to Microsoft. It was something synergistic.

Gates and Kildall even discussed the merger at some point. There was some kind of tacit agreement that Microsoft will not crawl into the operating system, and Digital - into languages. However, by the end of 1979, Digital began to distribute with some versions of CP / M BASIC not from Microsoft, which Gates and his colleagues perceived as betrayal.

However, Gates called Kildall right in the presence of Samgs to arrange a meeting with him and his team the next day. He said that these are very important customers, "so treat them normally." Sams was not happy about it. He was impressed by Gates and Microsoft, and “we just wanted to work with one person” on software.

But there was no choice. As you remember, CP / M worked on the Z80. Sams didn't just have to buy a license from Digital; he had to agree on porting the OS to the new 8088 architecture, and according to the schedule he needed. The next morning, he and the crew followed the plane to Pacific Grove, California, where Digital Research was located.

Mysterious events of August 22, 1980

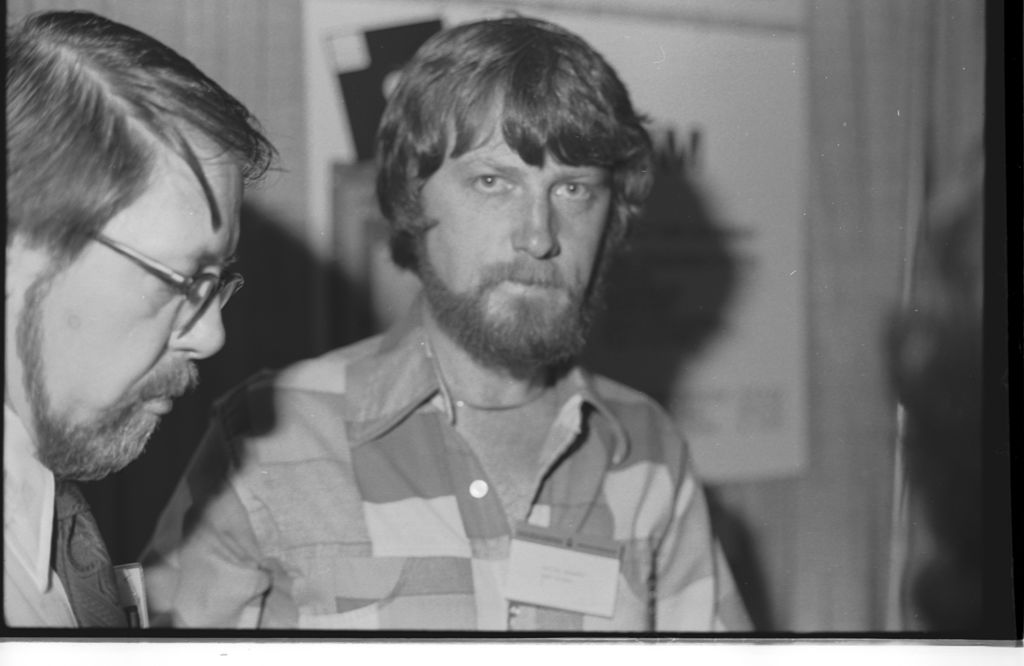

Gary Kildall in 1977

This moment is famous for the fact that the story becomes vague. Subsequently, Sams and Kildall asked many times what happened on August 22, 1980. Their stories are so incomparable by the facts that it is impossible to attribute this only to the relation to nuances or different interpretations of events. Someone, and perhaps both of them, just told a lie.

Sams argues that they and the team arrived at the Victorian building, which served as Digital headquarters, just in time, and found out that Kildall decided to use the good weather, and instead of meeting, he went flying on his plane. Sams and the company had to talk to Digital's business manager, Kildall's wife, Dorothy. Being shocked, Samms remained adamant and pulled out his NDA as a prelude to business.

At first glance, it was an abusive and unfair agreement, which, in fact, said that the other side would be convicted if it revealed the secrets of IBM, but IBM still remains immune from any lawsuits in the opposite case. Gates said that he "believes" them, and immediately signed the paper. Dorothy refused and said that she would first need to consult her lawyer. And while Sams nervously waited in the waiting room, he and his lawyer, Jerry Davis, hesitated until three in the afternoon, until finally they signed the NDA.

Since almost the entire day has passed, and the technical specialist, who would have needed to be engaged in porting, was absent, the discussions have hardly advanced. Sams left Digital disappointed and annoyed, with no hint of agreement, and immediately began to look for alternatives to these people.

For his part, Kildall (who died in 1994 under very strange circumstances ) admitted that he flew when Sams arrived at the meeting. However, he argued that he was not entertained by flights, but flew home after a business trip.He said that he had not seen anything terrible in having Dorothy communicate with the IBM team at the beginning of the meeting, since she was more involved in business negotiations than he. At the same time, he said that he had returned already in the afternoon, and it was he who convinced Dorothy and Davis to sign the NDA and continue negotiations.

After that, the talks went quickly, and IBM with Digital “shook hands” by the end of the day. Kildall also stated that he and Dorothy then flew off that evening, already on a commercial flight, to begin their vacation in Florida, and that the IBM group was flying the same flight. And there they talked about future plans.

Sams says he didn’t fly to Florida right after the meeting, but went back to Seattle to continue his conversation with Microsoft, acknowledging that it was possible a couple of team members could head back to Boca Raton. Years later, he was firmly convinced that he had never met Kildall at all, "unless he pretended to be someone else, being there."

Only in recent years, Sams softened his position, and said that "probably" that Kildall was at the meeting, but he "does not remember this." He also said recently: “We failed, Kildall failed, and Microsoft failed.” This can be perceived as the last refuge of a man who did not always speak the truth, but who knows. For both versions of events there are witnesses, partially confirming them. Digital's chief executive and Kildall's friend, Tom Rolander, said that he was on a business trip with Kildall, and that they met with Sams that day. Davis, a digital lawyer, says no agreement was made on that day, and other IBM employees recall that Sams, right after this expedition, said that Kildall was not at all at the meeting.

Microsoft 1987

And how to understand all this? You can compare the identity of Kildall with the personality of Gates. Popular descriptions of these events often reduce Gates and Kildall to cartoon characters, to a manic businessman from the east coast against a relaxed hippie from California. In fact, this is not so far from the truth. Both were great hackers, but otherwise could hardly be even more different. Gates was determined to prove his worth and win to everyone, again and again. When such a big fish like IBM came to him, he readily showed modesty, even cringing, because he needed it as the next stage of his career. (After he no longer needed them, everything changed.) Gates's ambition, though not the most delightful of his properties,made many of his partners respect Microsoft. Gates not only put together a very talented team, they all corresponded to the personality of their boss in that they were ready to plow like oxen and overcome all obstacles in order to get the job done right and outrun their rivals.

Kildall behaved in such a way that sometimes it did not seem that he was sure that he wanted to do business.

In one of the most unfortunate moments of the late 70s, Gary walked past the parking lot on the way to his work and walked down the street, suddenly realizing that he couldn’t force himself to go to work. He walked around the block three times until he could bring himself to meet another day at Digital Research.

It is impossible to imagine how any such doubts overcome Gates.

Kildall was important joy of hacking. And users had to wait patiently. He may have liked working with IBM, but they had to stand in line, like everyone else. And he certainly wasn't going to grovel before them. Jordan Eubanks, vice president of digital in 1980, says: "Gary liked parties more than business management." Besides the parties, Kildall liked the software. And Gates liked the software business. Yubanks:

The differences between Bill and Gary were astounding. Bill, seeing the opportunity, chased her, did everything possible, did more possible, without problems. Gary was set up like „Yes, I don’t care, I’m Digital Research. You will work with me on my terms. "

Jack Samms in the Triumph of the Nords, in 1996.

And there was the identity of Sams, or, more precisely, his corporate guardian. IBM was a big shot in the computer world, and expected to be treated accordingly. If they condescended to visits to such companies as Microsoft or Digital, they should have been worn, as with a VIP, and show that this company really wants to deal with them.

When Digital failed to show respect and gratitude in the way that Microsoft did - and whatever happens on that day, it is clear that this is the way it was; Eubanks describes that Dorothy was “shitty” about everyone, including customers — Sams was furious. “They don’t know who I am?” He was probably surprised. Clearly, Sams didn’t like the prospect of working with Digital instead of Gates before he got on a flight to California. As our mothers have always told us, if you start a business with a bad attitude, you usually get bad results.

One thing is clear: there was a verbal agreement, or not, or what impression Kildall had of it there, Sams was not satisfied with his experience with Digital. He asked Gates, who had already signed a consulting agreement this time, if he could find an alternative to CP / M. Gates said he would see what could be done. Sams says he continued to try to negotiate with Digital, but could not get consent to develop the 8088 CP / M within tight deadlines. Eubanks says that Kildalla this project simply did not seem so "interesting", despite its obvious need, and as a result he worked on him carelessly.

And then Gates came back with QDOS.

Ending

All Articles