Astronaut Scott Kelly talks about the destructive effect of space, where he spent a year

The cosmonaut from NASA Scott Kelly spent a year in space on the ISS. His memories of this unprecedented test of human exposure and physical activity raise questions about the possibility of future flights to Mars

Scott Kelly inside the Soyuz simulator before the mission. This capsule will be a rescue in case of disaster.

[ This was the first American astronaut to remain in space for so long. In addition, in this mission, a new, not previously used equipment was used, detailing the condition of the crew. Absolute space records belong to the Russian cosmonaut Gennady Padalka , who spent a total of 878 days in space, and Valery Polyakov - he spent at the Mir station, which is now non-existent, for 437 days and 18 hours without a break / approx. trans. ]

I sit at the head of the dining room in my home in Houston, Texas, and finish dinner with my family: my longtime companion Amiko, my twin brother Mark, his wife, a former congressman, Gabby Giffords, their daughter Claudia, our Father Richie and my daughters, Samantha and Charlotte. The everyday thing is to sit at the table, have lunch with your loved ones, and many do it every day, without really thinking about it. But personally, I dreamed about this for almost a year.

I so often imagined how I would participate in this dinner. Now that I am finally present here, it seems to me not quite real. The faces of my beloved people, whom I hadn’t seen for so long, the chatter of several people at the same time, the tinkling of instruments, the gurgling of wine in glasses - all these are unfamiliar sounds. Even the feeling of gravity holding me on the chair seems strange to me, and every time I put a glass or put a fork on the table, a part of me is looking for a piece of sticky tape or a piece of adhesive tape that should hold them.

Now March 2016, and I have already spent on the Earth, after a year in space, exactly 48 hours. I push off the table and struggle to get up, feeling like an old man coming out of a chair.

“Everything, I can no longer,” I declare. Everyone laughs and offers me rest. I set off in the direction of the bedroom - 20 steps from the chair to the bed. In the third step, the floor suddenly leaves me, and I stumble over a flower tub. Of course, it's not about the floor — this is my vestibular system trying to cope with gravity. I'm getting used to walking again.

“For the first time I see you stumble,” says Mark. - Not bad cope. A former cosmonaut, Mark knows from his own experience how to return to Earth. I walk beside Samantha and put my hand on her shoulder, and she smiles at me.

I get to the bedroom without incident and close the door. My whole body hurts. All joints, all muscles protest against oppressive gravity. And I feel sick, even though I didn’t vomit. I take off my clothes, get into bed, with pleasure feeling the sheet, slight pressure of the blanket on the body, the pomp of the pillow under my head.

Over all of this last year I missed a lot. I can hear the cheerful conversations of my family behind a closed door - I have not heard these voices for a long time without the distortions caused by the telephone connection jumping between the satellites. I fall asleep to the soothing sound of their talk and laughter.

I am awakened by a strip of light. It's morning already? No, this is Amiko going to bed. I slept just a couple of hours, but I feel disoriented. I have to exert myself only in order to start moving and tell her how bad I feel. Now I feel very sick, shivering, and the pain has intensified. After the previous mission, I did not feel that way. This is much worse.

Scott Kelly with his girlfriend Amiko on Red Square in Moscow

Two future cosmonauts, Mark (left) and Scott Kelly, 1967

“Amiko,” I finally manage to say. She is anxious to hear my voice.

“What is it?” Her hand is on my wrist, and then on my forehead.

Her skin seems cool to me, but that’s because I'm hot. “I feel bad,” I say.

* * *

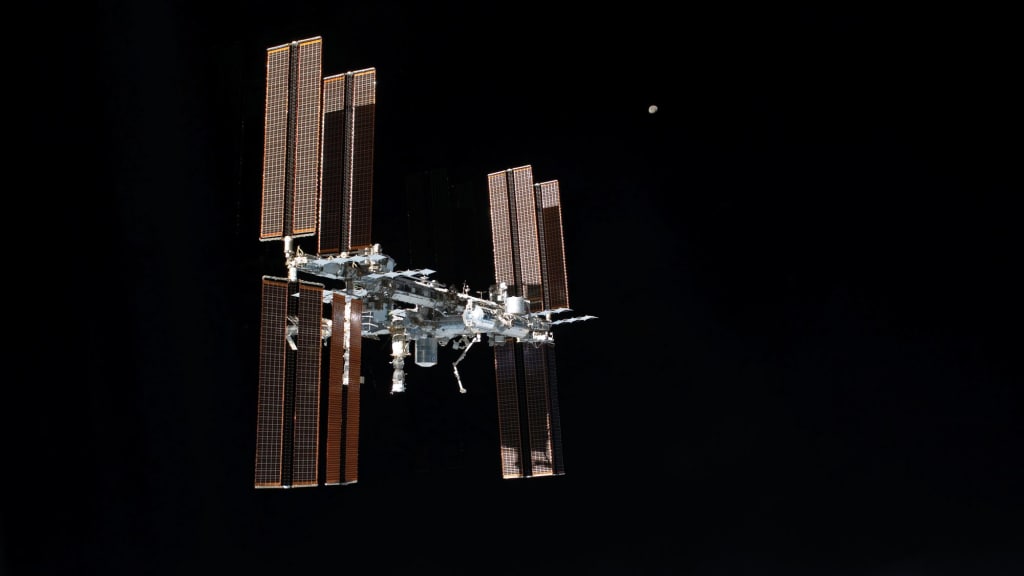

Last year, I spent 340 days with Russian cosmonaut Mikhail “Misha” Kornienko on the International Space Station (ISS). We are working in a program that is part of NASA's planned trip to Mars. It is designed to monitor the effects arising from long-term stay in space. This is already my fourth flight into space, and by the end of the mission I will spend 520 days there - more than any other NASA astronaut. Amiko had already gone through all this and was my main support when I spent 159 days on the ISS in 2010-2011. Then I also experienced the consequences of returning to Earth, but they didn’t come close to what I feel today.

ISS

I hardly rise. I find the edge of the bed. Feet down. I sit down. I get up. At every step, it seems to me that I am battling with quicksand. When I finally take a vertical position, I feel a terrible pain in my legs, and besides that I feel something more frightening: how blood rushes down to my legs. It is a kind of sensation when you are standing on your hands, and the blood rushes to your head - just the opposite.

I feel the leg tissue swelling. I hardly make my way to the bathroom, shifting my weight from foot to foot with obvious effort. Left. Right. Left. Right. I reach the bathroom, turn on the light and look at my feet. These are swollen, alien stumps, and not legs at all. “Oh, shit,” I say. “Amiko, look.” She kneels and squeezes her ankle, and she squeezes like a ball of water. She looks up with excitement in her eyes: “I can't even grope for the bones in my ankle,” she says.

“Yes, my skin burns,” I tell her. Amiko quickly studies me. I had a strange rash on my back, on the back of my legs, on the back of my head and neck - everywhere in the places that touched the bed. I feel her cold hands touching my hot skin. “It looks like an allergic rash,” she says. “Like urticaria.”

I do my chores in the bathroom and make my way back to bed, thinking about what to do. Usually, waking up with such a feeling, I would go to the emergency service. But no one in the hospital saw symptoms appearing after a year spent in space. I'm crawling back to bed, trying to invent a way to lie so as not to touch the rash. "

I hear Amiko rummaging in the medicine cabinet. She comes back with two ibuprofen tablets and a glass of water. She settles side by side, and in her every movement, in every breath, I feel how she is worried about me. We both knew about the risks of the mission I subscribed to. After six years spent together, I understand her perfectly, even without words and in the dark.

I try to fall asleep and think about whether my friend Misha, at his place in Moscow, suffers from swollen legs and a rash. I suspect that yes. That is why we signed up for this mission: to find out the details of how a long-term space flight affects the human body. Scientists will study the data received from Misha and from the 53-year-old me for the rest of our lives and even after that. Our space agencies will not be able to throw us further into space, somewhere on Mars, until we can learn more about strengthening the weakest links in the chain, making space flights possible: the human body and mind.

I am often asked why I volunteered for this mission, knowing all the risks: the risk of launching, the risk of going into open space, the risk of returning, the risk of being in a metal container orbiting the Earth at a speed of 28100 km / h. I have several answers to this question, but none satisfy me completely. None gives a complete answer.

Scott Kelly (left) performs a dangerous spacewalk with the ISS

* * *

Usually, the mission on the ISS lasts from 5 to 6 months, so scientists have a large stock of data describing what is happening with the human body in space for such a period. But very little is known about what happens after six months. Symptoms, for example, can worsen dramatically after nine months, or vice versa, remain unchanged. We do not know this, and there is only one way to find out.

During our mission, Misha and I collected a lot of data about ourselves for further study, which was quite time consuming. Mark and I are identical twins, so I also participated in an in-depth annual study that compared us to the genetic level. The ISS was a world-class laboratory, and besides experiments on the study of man, in which I played the role of one of the main objects of study, I also spent a lot of time working on other experiments - fluid physics, botany, burning, and observing the Earth.

Telling the audience about the ISS, I always explain the importance of scientific research conducted there. But it was also important to me that this station serves as a reference point for our species in space. From there we can learn more about how to move forward. But both the risks and the cost were high.

During my previous flight to the space station, which lasted for 159 days, I lost bone tissue, my muscles atrophied, my blood was redistributed throughout my body, which caused my heart walls to stiffen and tighten. What is worse, I had vision problems, like many other astronauts. The irradiation was 30 or more times greater than that of a human on Earth — it was about 10 fluorography per day. Such exposure increased the risk of a fatal cancer to the end of my life.

But all this does not compare with the most terrible risk: that something terrible will happen to someone of my loved ones, while I will be in space without the possibility of returning home.

* * *

I was at the station for a week, and I was already better able to figure out where I was, than after I woke up for the first time. If I had a headache, I knew that this was due to the fact that I sailed too far from the fan that was blowing in my face. Yet I still quite often lost my orientation in space: I woke up, being sure that I was upside down, because in the dark, without gravity, my inner ear was building a random conjecture about the position of the body in a confined space. After turning on the light, I felt an illusion, it seemed to me that the room was spinning rapidly and taking the desired position around me, although I knew that in fact it was my brain that was adapting to new data from the senses.

The light in my room took a minute to warm up to full brightness. There was barely enough space for me, a sleeping bag, two laptops, a handful of clothes, toiletries, photographs of Amiko and my daughters, and a few books. I studied my schedule for today. I looked through the mail, stretched, yawned, rummaged in the bag of accessories tied to the wall at the left knee in search of toothpaste and brush. He brushed his teeth without getting out of his sleeping bag, swallowed the paste and washed down the water from the bag with the help of a straw. In space, there is nowhere to spit.

* * *

I did not have the opportunity to spend time outside the station before the first of the two planned spacewalks, which occurred only seven months after arrival. The fact that you can't leave the space station whenever you want is one of those things that people find hard to imagine. The procedure of putting on the spacesuit and going into space takes many hours, requires the full attention of at least three people at the station, and dozens on Earth.

Spacewalk is the most dangerous thing we did in orbit. Even if the station caught fire, if it was filled with poisonous gas, if a meteor flashed the residential module and the outer space exploded inside - the only way to escape from the station was the Soyuz capsule, which also required a lot of planning and preparation to start. We regularly trained in emergency situations, and in many cases we tried to prepare the Soyuz for launch as quickly as possible. No one had yet to use the Soyuz as a lifeboat, and everyone hoped that they would not have to.

* * *

I opened the food container tied to the wall and caught a bag of dehydrated coffee with cream and sugar. I swam to the boiler located in the ceiling of the laboratory, which poured boiling water, inserting the needle into a special tip in the bag. When it was full, I replaced the needle with a drinking tube — in this case, the fluid could not spill into the module. At first it was surprisingly unpleasant to drink coffee through a plastic bag, but now I don’t care.

I looked at the breakfast options, looking for a bag of granola , which I liked. Unfortunately, everyone else liked her. I had to choose the dehydrated eggs and restore them all from the same boiler, and warm up the sausages in the box for heating food that looked like a metal briefcase. I cut the bag, then, since we did not have a sink, I cleaned the scissors, licked them (each of us has our own scissors). With a spoon, I took the eggs out of the bag and placed them on a tortilla cake — it's good that the surface tension kept them in place — added sausages, sauce, wrapped it and ate this burrito, watching the morning news on CNN.

During the whole process, I kept myself in one place, putting my toe under the rail on the floor. The handrails were placed on the walls, floors and ceilings of each module, as well as at the hatches connecting the modules, which allowed us to launch ourselves in the flight through the modules, or stay in place without leaving it. Many features of life in weightlessness were interesting - but not food. I missed being able to sit on a chair while eating, relax, and pause for conversations with others.

* * *

In this expedition, more than 400 experiments were conducted on the ISS. NASA scientists divided the research into two major categories. The first was related to research that could benefit life on Earth. These included studies of the properties of chemicals that can be used in new drugs, the properties of combustion for more efficient use of fuel, and the development of new materials. The second category solved the problems of future space exploration: testing new equipment for life support, solving technical problems of space flights and studying new ways to meet the demands of the human body in space.

Science occupied about a third of my time, and the study of man - three quarters of this amount. I needed to take samples of my own blood and the blood of my colleagues, which would then be analyzed on Earth, I kept a diary of everything from food eaten to mood swings. I checked my reaction at different times of the day. I did an ultrasound of the blood vessels, heart, eyes, and muscles. I also participated in the experiment with the movement of fluids in the body - a special device pumped blood into the lower part of my body, where it is usually held by gravity. It was a test of a leading theory explaining vision problems for some astronauts.

But in fact, studies from these two categories often overlap. If we can learn how to prevent the destructive effect of bone loss in microgravity, the solutions can then be used to treat osteoporosis and other bone diseases. If you can figure out how to keep your heart healthy in space, this knowledge can be useful on Earth.

The influence of life in space is very similar to the effect of aging, which we all are exposed to. We grew lettuce by exploring the future of space travel — astronauts going to Mars will only have fresh food from fresh food — but it also taught us how to effectively grow food on Earth. A closed-loop water supply system on the ISS, where we process our urine and convert it into clean water, will be critical for flights to Mars, but it also has promising applications for treating water on Earth - especially in places where there is a shortage of clean water.

* * *

I told the flight surgeon, Steve, that I felt well enough to get to work immediately after returning from space, and that was true - but after a few days I felt much worse. This is what happens when you allow your body to be used for scientific purposes. I will be an experimental object until the end of life. But a few months after returning to Earth, I already felt much better. I traveled around the country and around the world, talking about time spent in space. It is pleasant to see how people are interested in my mission, how many children instinctively feel interest and think about flights into space, and how many people with me think that Mars will be our next step.

I also know that if we want to fly to Mars, it will be a very, very difficult task, it will be very expensive both in money and, probably, in human lives. But now I know that if we decide to do this, we can.

Excerpt from the book " Endurance: a year in space, and all life, full of discoveries "

[ About the terms astronaut / cosmonaut: by agreement, people who have flown into space due to the power of Roscosmos are called cosmonauts , including and in English, cosmonaut. Scott Kelly flew the ISS aboard the Soyuz TMA-M / approx. trans. ]

All Articles