People-computers

In the 20th century, the British personal computer industry lagged behind the American one in three years on average for purely practical reasons. And it’s not that modern American cars could be bought. Commodore alone sold 45,000 PET models in the first three years of its presence on the island. Other, less common models, for example, TRS-80s, Apple IIs, Atari 400s and 800s, could also be bought with funds available. The question rested only in money. When a pound cost about $ 2.5, even the most basic PET models would cost you no less than £ 650, and the Apple II system, which became practically standard in the US by 1981 - 48 K II Plus, a color monitor, two drives and a printer was approaching the mark of £ 2000. To understand how high the threshold was for such prices for the average Briton, you need to learn something about life in Britain in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The British economy had already been in a deplorable state for quite a long time, suffering from some post-imperial sickness, periodically emphasized by such unpleasant shocks as the “ three-day week ” when the energy shortage caused by the coal miners' strike caused the government to order business enterprises day to week, and the " winter of discontent " of 1978-79, when strikes in a multitude of industries almost stalled the economy and daily life. These events ensured the election of the most controversial figure in the post-war political history of Britain, Margaret Thatcher, with the platform that promised to drag Britain, even those who were fighting back and indignant, into the modern era, by cutting back all social benefits introduced after World War II.

But after her election, there was no rapid improvement in the situation. The government forced asceticism, a large part of the industrial base was buried by privatization, and the situation got worse. By 1981, unemployment was at the level of 12.5%, entire cities turned into industrial deserts, riots took place almost daily, and wherever Thatcher appeared, indignant crowds besieged it all the time. There was a feeling not just of a strong recession, but of great danger. That summer, The Specials group summed up the country's mood in the apocalyptic single "Ghost Town" [ghost town], which hit the top of the charts. After a strong failure, the situation began slowly and difficult to recover, but a whole decade passed after unemployment fell to an acceptable level, and the modern economy that Thatcher promised promised to take root with the beginning of the optimistic era of Cool Britain [the economic program was supported by export oil produced in the North Sea - approx. trans.].

Suffice it to say that then most of the British would not be able to pay for computers, even if they cost as much as the Americans paid for them. PETs were sold to business consumers, and the TRS-80 and Apple II were sold to a small number of wealthy eccentrics who could afford it. For ordinary consumers, a parallel home industry has appeared with affordable prices. It began in 1978, three years after the appearance of Altair in North America, with self-assembly kits, which allowed people as a hobby to solder devices from switches and flashing lights. Therefore, exactly on schedule, the British equivalent of the mentioned trinity of 1977 appeared in the country in 1980.

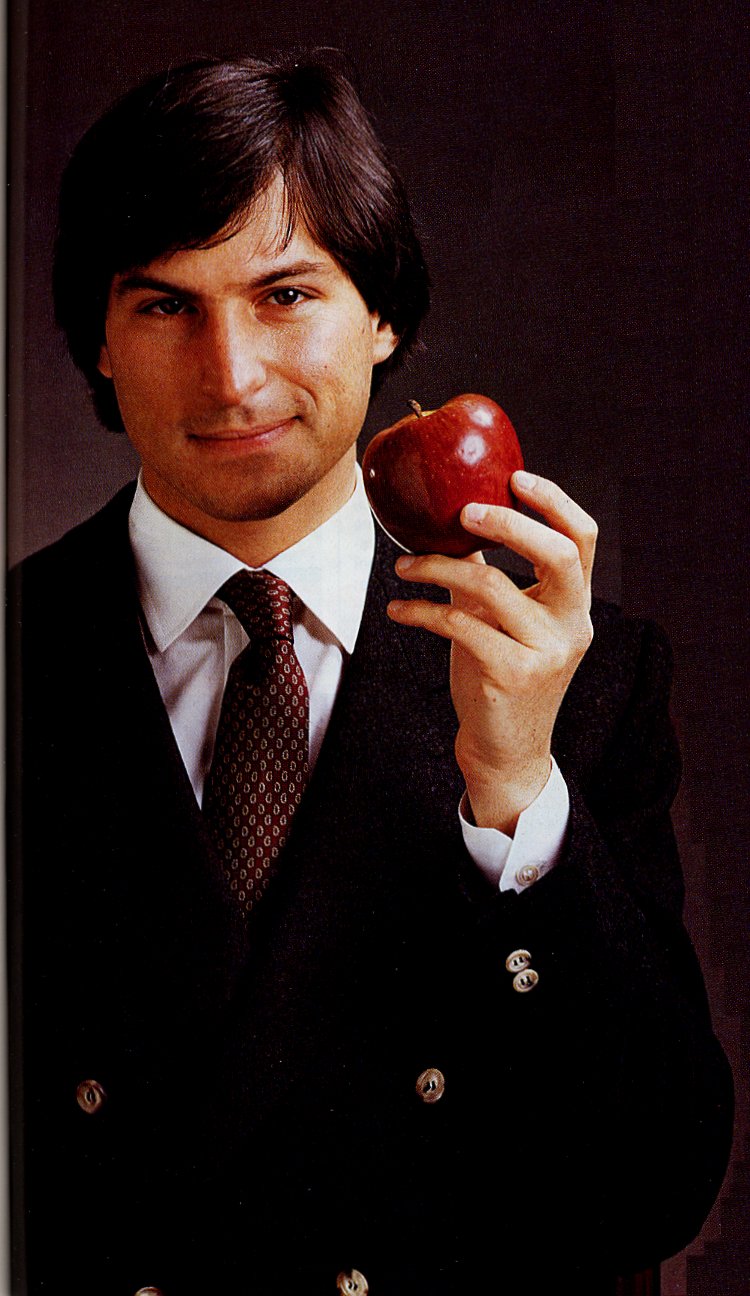

In the early stages of the birth of the PC era, so many outstanding people can be found, and their photographs describe them completely. For example, Steve Jobs, a cute brisk wizard, whom you would hardly have entrusted your daughter.

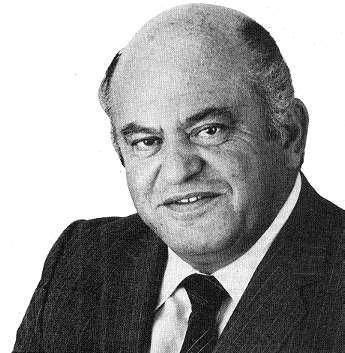

Jack Tremel , looking as if he (if he discarded the Jewish roots) should sit behind a pile of spaghetti and mumble something about broken kneecaps.

Or the man who went down in history as the first who was able to bring available computers to the British markets, Clive Sinclair . He looks like a crazy genius inventor, capable of creating gadgets for James Bond - or Maxwell Smart [character of Mel Brooks' comedy and parody series). trans.]. Leaving it at home for a short while, upon your return, you would find that your cat is on fire, and your daughter's hair has changed color.

Despite the complete absence of specialized education, Sinclair learned everything while writing articles for electronic journals, and in 1961 founded Sinclair Radionics, whose name would be ideal for a workshop of insane genius. For several years she sold kits for the manufacture of radio, amplifiers, test equipment and other things, and then the company launched a line of consumer electronics. Within its framework, they produced breakthrough gadgets that had absurd design flaws and the worst possible quality control. You can recall Sinclair Executive , one of the first calculators that can fit in your pocket, which had an unpleasant tendency to explode (!), Being left without using for a long time. There was also a Microvision portable TV. Unfortunately, Sinclair did not bother to ask if anyone wanted to watch TV on a 2 "black and white screen - and the device failed in the market.

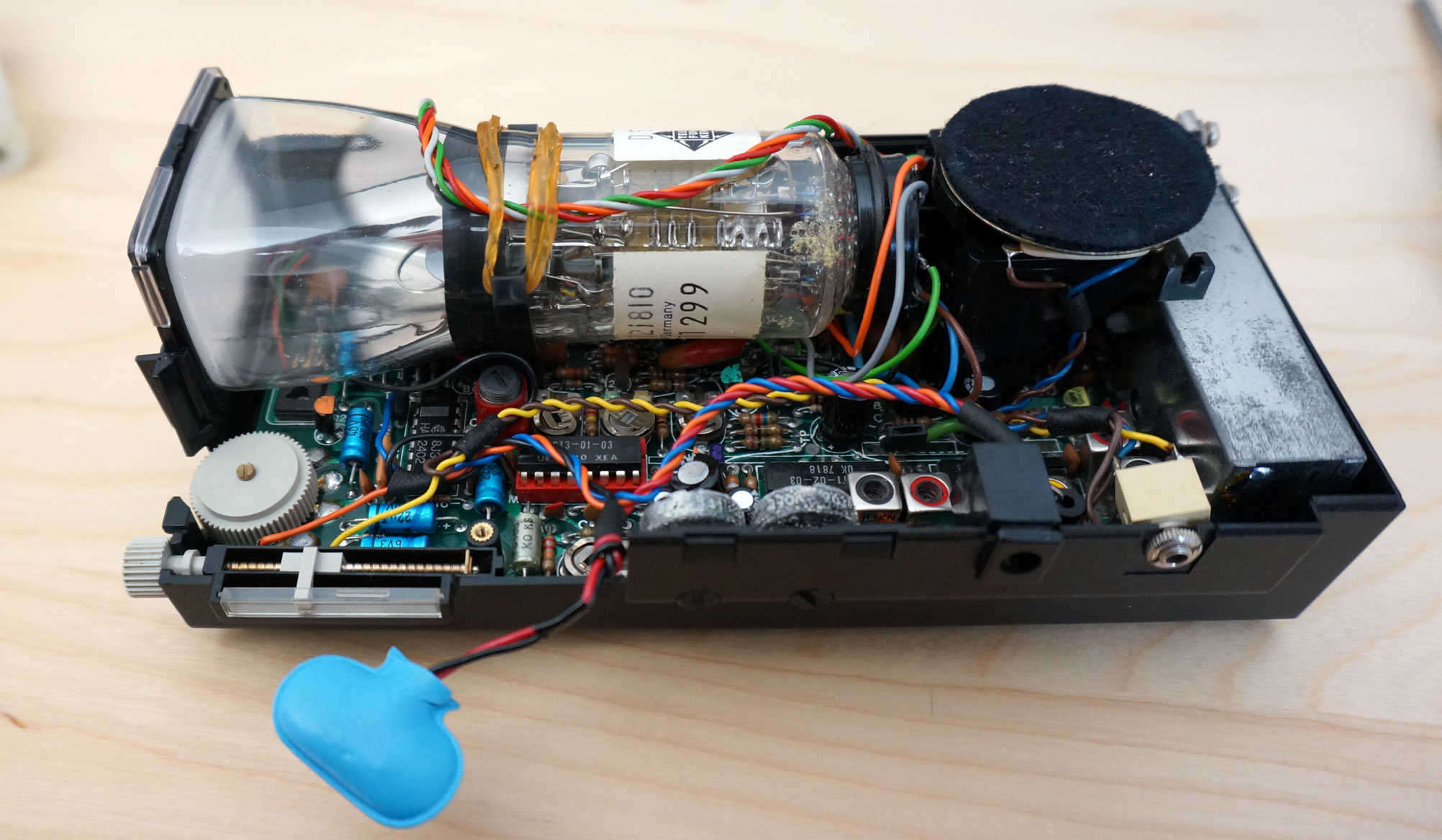

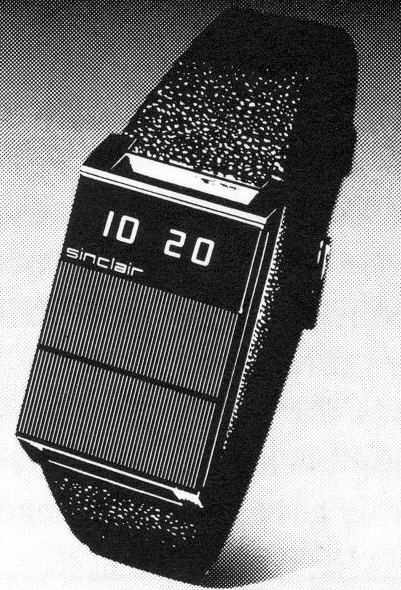

But the stereotypical, or even satirical, product of Sinclair was the Black Watch.

Plus, they can be attributed to the fact that it was one of the first electronic watches. In the minus - hmm, where to start? Black Watch chronically unreliably showed time, which can hardly be attributed to the merits of watches. They were too sensitive to climate change, and went at different speeds at different times of the year. The batteries, at best, lasted ten days, and replacing it was almost as difficult as completely collecting the watch from scratch. Like many other Sinclair products, they could be purchased both assembled and as a do-it-yourself kit. They were prone to sudden destruction when the clamps holding parts of the watch suddenly refused. But this was not the worst - they, which was characteristic of Sinclair products, also exploded without warning.

They were released at the end of 1975, and their fiasco, coupled with the flow of cheap Japanese calculators, marked the beginning of the end of Sinclair Radionics. The British National Industry Committee bought out a controlling stake in the company in 1977, but found that it was completely impossible to work with Clive, and realized that hopes for a reversal of the trend are very difficult to realize. As a result, after Thatcher’s election, the committee closed the company, since it was precisely this kind of confusion between private business and public administration that the new administration tried to avoid. By that time, Clive had already organized another company, sneakily trying to free himself from government intervention in his management decisions. She called it Science of Cambridge, so as not to glow much in the title. This company is also starting a PC boom in Britain.

To see Clive Sinclair's slightly exaggerated but entertaining biography, you can watch the BBC People-Computers TV movie [Micro Men] based on real events. Clive was a talented inventor with a penchant for the art of the possible, and with a determination to give people products at affordable prices - a populist in the best sense. He was also incredibly stubborn and arrogant, one of those extremely tedious people who adore talking about his IQ. For two decades he was chairman of the British branch of the intellectual community Mensa . In a typical interview for Your Computer magazine in 1981, he stated: "I made mistakes, everyone makes mistakes, but I never made them twice." A person with more modest mental abilities, for example, your humble servant, might have noticed that his story of exploding products indicates a person who seems to be making the same mistake time after time, believing that he can avoid the difficult process of improving the product thanks to genius of the original idea. But why me?

Sinclair was also connected to those computer sets with flashing lights that I mentioned, but he really entered the market with the launch of the ZX80 in the early 1980s - a £ 100 car that inspired Jack Tremela to create the Commodore VIC -20. And between these two people can reveal some similarities - both were self-centered directors, driven out of the market calculators cheap Japanese competitors. But do not get involved in the comparison. Sinclair was an uncompromising researcher, full of children's enthusiasm for gadgets and the social potential of technology. Tramel was a businessman. He, paraphrasing one of the most famous speeches of Steve Jobs, would gladly sell his life and sweet water, if this activity would give him the desired competitors.

The ZX80 was again available both as a semi-assembled kit and as a ready-to-use product. With its tiny body and membrane keyboard, it looked more like a big calculator than a computer. And indeed, with 1 KB of standard memory, he could hardly do something more complicated than adding numbers, while the user did not shell out for expansion. The standard BASIC environment was very strange and seemed almost deliberately unfriendly to the user, and also possessed the usual problems of Sinclair with reliability, especially the tendency to overheat. At least there were no reports of explosions of the ZX80. The design was so minimalistic that it didn’t even have a video chip, and he relied on the CPU for video signal generation exclusively using software methods. One of the most unique “features” of the computer came from this: since the CPU could generate video only if it was not busy with something else, the screen went out while the program was running, and it blinked every time even when the user simply pressed a key. But it was a real computer, and the first one available to most Britons. Sinclair sold 100,000 of these computers in less than 18 months.

Science of Cambridge was not the only company that left its mark on the growing computer market in the 1980s. Another young company, Acorn Computers, released its own Acorn Atom that year.

Atom cost 50% more than the ZX80, but it was still much less compared to any American device. For the extra money, you received a much more convenient computer, with a normal keyboard, with a double memory of 2 KB (although such a volume was also not enough for what), with a constantly flashing display, and with less, let's say, a unique interpretation of BASIC. The rivalry between Sinclair and Acorn took place on a personal level. The head of Acorn, Chris Curry , for twelve years was Clive Sinclair’s right hand. They broke up at the end of 1978, and the irony of the situation was that Curry wanted to produce a new microcomputer, the potential of which Sinclair was not visible at that time. Curry founded Acorn with German Hauser, and a year later - when Sinclair suddenly joined the religion of microcomputers - he walked with his former boss on a par.

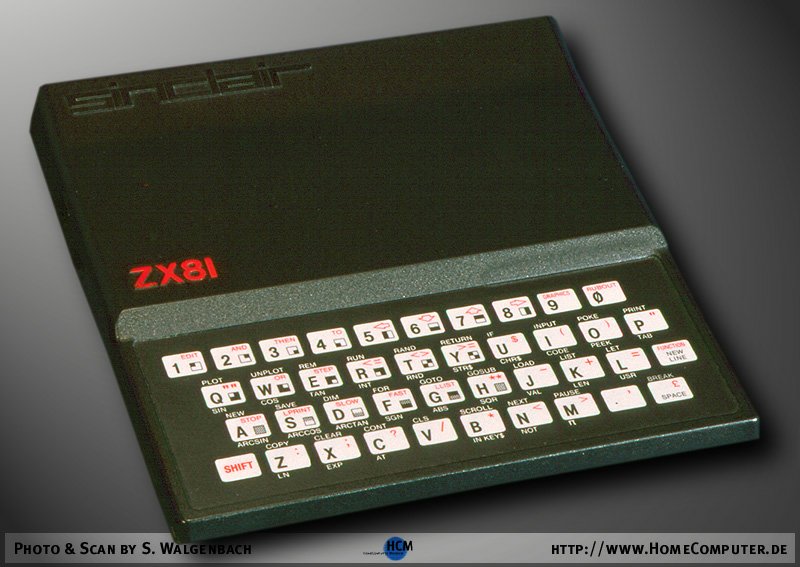

The next year, 1981, was turning. Sinclair, who changed the name of the company to Sinclair Research after the death of Sinclair Radionics, presented the ZX81 in March, developing the ZX80 design and again reducing its cost, to £ 50 for a do-it-yourself set and £ 70 for an assembled unit.

Among the improvements to the ZX81, we can mention the “slow mode” of work, in which part of the processor time was always reserved for updating the display, because of which it ceased to blink, but the processor also worked noticeably slower. It could work with floating point numbers, which was not possible on the ZX80. Of course, it was a product of Sinclair, with all the consequences. Expansion of memory to 16 KB was not well inserted into the slot, it sometimes fell out with a disastrous result. And in general, most of the connectors suffered from a similar problem, which made it necessary to tiptoe around the car. People living near the railroad were very unlucky.

Commodore VIC-20 appeared in the same year at an initial price of £ 180. The most inexpensive of all inexpensive North American cars, the VIC-20 could boast 5 Kb of memory and color graphics, which was better than the Sinclair or Acorn without add-ons. Hence the higher cost.

In North America in 1978, one could observe the emergence of a commercial software market. Hobby lovers such as Scot Adams began recording their programs on tapes, packing them in zip-packs and selling them. Supporting the three-year rule, the local software market in Britain began to emerge in 1981, with the same propensity for a do-it-yourself system — with manually copied cassettes and improvised packaging. On one of these tapes one could hear the sounds of a children's game and other extraneous noises. Software mostly meant games, of course, and most of the games were text quests.

A good example of the first British national game can be called Planet of Death , a game for the ZX80 and ZX81, released around June 1981 by Artic Software, founded by two students, Richard Turner and Chris Thornton the year before. Unlike the first American programmers who wrote text quests, Turner and Thorntnon could use existing games as an example, thanks to the Video Genie computer, the Hong Kong clone TRS-80 Model 1, which became more popular in Britain than the original.

They wrote their program on Genie, which worked on the Zilog Z-80 Sinclair processor, in order to transfer it to the more primitive Sinclair computers. In the series of adventure games, the first of which was Planet of Death, the strong influence of the work of the American game developer Scott Adams was well seen - starting with what the player’s instructions called a “puppy” and ending with an adventure numbering system designed to help the user to collect the entire collection ( with one difference - Artic used letters instead of numbers, so Planet of Death was designated Adventure A).

Planet of Death is not a particularly inspiring example of Britain’s first narrative game. Perhaps you can only admire the enthusiasm of programmers. Scott Adams, at least, always finished games before releasing them. Planet of Death looks like a project that has been fired from the bottom of a modern competition for an interactive text game , albeit without the use of the language Inform that is built into modern IF programs. It looks as if Turner and Thornton have used up all their memory, and they have thrown it all away. If you think about it, then this is a very real scenario. There are a lot of bugs in the game, a labyrinth annoying with the fact that it leads nowhere, branches and semi-completed puzzles distracting from the main narration, and all this works on a dull parser that considers that “with” is a verb. However, as much as the ZX80 and ZX81 were real computers, albeit limited, Planet of Death was a real adventure game, the first of all that most Britons could see, and it was selling well enough for Artic to release a whole line of games. She stands at the origins of the modern scene of adventure games, which has become more vibrant and fertile than the American.

A sign of the growing popularity of PCs in Britain is the fact that the omnipresent WH Smith sales network [books, magazines, entertainment products - approx. in the 1981 holiday season, I started selling the ZX81 with the slogan "Your first step towards personal computers." Just as the appearance of VIC-20 in K-Mart’s US stores marked a similar paradigm shift, popular British stores soon sold not only Sinclair computers, but Acorn and Commodore as well. In just a few years, computer sales in Britain surpassed the United States in terms of per capita, and Britain became the most computer-crazy nation on the planet.

All Articles