Aging and menopause - two population control programs

What is aging? The programmed murder. What about menopause? Programmed castration. Two mechanisms of population control that genes have perfected over billions of years.

Why are genes being so cruel to us? For the same reason that they do everything else — to maximize the integral of their reproduction over time. That is, it is important to them not the momentary maximum of the number of copies, but the area under the curve of the number of these copies in time. Like wise economists, gene cartels are not striving for explosive growth, which is fraught with collapse, but for stable, long-term sustainable growth to infinity.

Why do genes need to copy themselves? Then, why does the electron “need” to the lowest possible orbital, and the free radical to oxidize someone. So it is in our universe. And, by the way, the desire to maximize entropy, it seems, generally underlies the phenomenon of living systems (self-applicators) - at least if the calculations of Jeremy Ingland are correct.

Well, okay, let's go back two levels of abstraction above - from physics to biology. Here somehow familiar. Why do genes need mechanisms for population control? At the intuitive level, this is understandable even to a child. Indeed, it is not without reason that almost any person who first hears the proposal to stop aging immediately asks the question: “What about overpopulation?”.

Yes, overpopulation threatens genes with extinction - if their replicators eat all the nutritional resources, they will die of hunger themselves, and the team of creator genes will disappear into oblivion. And gene cooperatives that have not learned to control the population of their copiers are likely to rest for a long time in this Summer. To this day, those who have mastered this skill (aging species), or those who have learned to survive long periods of adverse conditions (plants, hydra, etc.), have survived. Although many species can do both: for example, nematodes, they can turn off aging at the larva stage if they feel a lack of nutrients in the environment.

Fortunately, thanks to the hypertrophied brain that gave us the scientific and technical progress, the rational human population is not threatened with over-extinction, but our single-celled ancestors were threatened for billions of years. I think overpopulation was the cause of the extinction of many species due to the depletion of resources of the overgrown population, until the cells invented apoptosis and telomeres, and the multicellular cells behind them did not do the same at the next level of fractality — they did not invent aging (phenoptosis) and menopause (replicative aging of the body).

By the way, the female reproductive system is the shortest-living system of our body. The term of its operation is about 35 years (from 14–15 to 50 years), with the last 10–15 years (after 35) this functioning is very mediocre. Other body systems are also guaranteed to deteriorate with age, but not so rapidly:

By the way, with the onset of menopause, other negative processes are also accelerated, for example, sarcopenia and osteopenia (loss of muscles and bone tissue):

There is an opinion that menopause is an exclusively human prerogative. Like, here we are so great, extended our lives to such an extent that we overtook our physiological limit of the reproductive system. But it is not. Menopause (or, more precisely, the post-reproductive period of life) is in many species - from flies and worms, to elephants, whales, cows , gorillas and macaques .

It is necessary to clarify that formally, a pause is the cessation of the menstrual cycles, but in its meaning is the loss of the body’s ability to reproduce. And here lies the misunderstanding of how widespread this phenomenon is in nature. Menstrual cycles are observed only in some mammals (human, chimpanzee, bat), but very many have a “post-reproductive period of life”, as I have already mentioned. Therefore, later, when I will talk about menopause, I need to understand what I mean exactly the phenomenon of age sterilization (that is, loss of reproductive function), and not the narrow meaning of this term in the sense of stopping menstruation.

And, of course, menopause, like aging, is programmed. The reproductive system does not wear out due to use, but is deliberately destroyed. That, from the point of view of population control, is absolutely logical: aging guarantees the outflow of new individuals from the population, and menopause restricts the influx.

As I have already mentioned, this method of population control is not a multicellular invention. Evolution, so loving fractality, has introduced it even from single-celled. And the telomeres that impose the Hayflick limit on the maximum number of cell divisions are, in fact, exactly the same mechanism that limits the progeny of each individual cell.

What clears this limit for single-celled and increases new telomeres? Sexual reproduction, that is, gene exchange, as a result of which a new individual is formed, receiving “permission” for the next ~ 50 divisions. Like the new female multicellular. By the way, males do not count, they generally do not participate in reproduction. Their role is only to give their partner a key in the form of a second set of chromosomes, which will open a casket with permission to reproduce the unicellular “host” of the female. This host is a sexual cell line, which was originally designed by this female to replicate its genes.

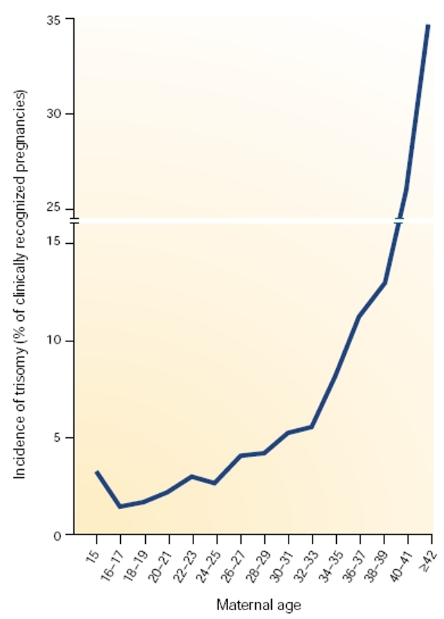

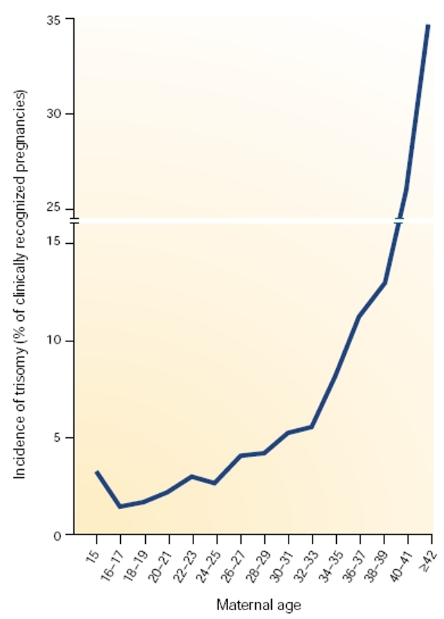

And this owner imposes very strict restrictions on reproduction for his creation. Even before the reproductive function of women finally turns off at 45–55 years old, it begins to actively deteriorate from the age of 35. Not only does the risk of egg abnormalities increase from less than 0.1% in 35 years to 3.5% in 38–40 years, and the risk of fetal trisomy (for example, Down Syndrome) increases from 5% in 38–40 years to 20% after 44 years, the mother’s risk of dying from childbirth also increases by a factor of 10 between 20 and 40 years.

Who is leading this process of active destruction of the reproductive system? The one who initially launches this system is our brain, or, more precisely, the hypothalamus with the pituitary gland.

Here are the key findings from a research on the topic:

In principle, the understanding that menopause does not occur due to the deterioration of the reproductive system or the depletion of ovarian stocks was among leading gerontologists back in 1950–70. Dilman, Averitt, Frolkis, Aschheim wrote about this more than half a century ago. Here is a quote from the 1977 book of my favorite “Hypothalamus, pituitary and aging” :

Aschheim, by the way, was one of those who set up a key experiment that showed that transferring young eggs to an old rat does not restore its estrous (ovulation) cycles. But if old, post-reproductive eggs are transplanted into a young rat, from which her own were previously removed, then these old eggs do not cause cessation of cycles in such rats. That is, the role of eggs in the termination of cycles is secondary:

Anyway, with eggs (oocytes) we have a strange story. 90% of them are killed before puberty: the embryo has more than 6 million, and at the time of the first menstruation there are less than 500 thousand. Although this is a thousandfold excess. Over a lifetime, no more than 500 ovulations occur in a woman. But the eggs are killed constantly, and with age, faster and faster, and exponentially:

Why does nature need to create 6 million eggs, if you use no more than 500 of them? One hypothesis is to increase the chances of genetic mutations. Yes, yes, just to increase. Because only mutations in the germ cells are inherited. And mutations are the driving force of evolution. After all, they create new variants of genes. Although women find it difficult to cope with men, who create hundreds of millions of new sperm cells every day , that is, the risk of mutations in men is 4–5 orders of magnitude higher.

There is another theory about why the female body produces so many oocytes, in order to thus minimize mitochondrial mutations in these egg cells. Presumably, when there are a lot of eggs, it will be possible to choose for each ovulation cycle in some way the one with “better mitochondria”. But this theory seems to me wrong for several reasons.

First of all, mitochondrial respiration is completely disabled in oocytes, so free radicals do not form in them, and their mitochondria do not “break down” over time, unlike other cells. Secondly, if the goal was to minimize mutations, no system would repeat the mutagenic process of creating new oocytes 6 million times, when it would be enough for it to repeat it only 500 times.

And, finally, the probability of mutation of the mitochondrial DNA during the division of each oocyte is much less than the probability of mutation in nuclear DNA: mtDNA contains only 16 thousand base pairs against 3 billion in nuclear DNA. In addition, each oocyte has as many as 100 thousand independent mitochondria, and the mtDNA mutation in one or several of the mitochondria will not affect mtDNA in all the others.

Protection of mitochondria in oocytes throughout the life of an individual could be the initial goal in separating the germ and somatic cell lines of our ancestors millions of years ago, as well as in disabling the function of mitochondrial respiration in the germ line (so that free radicals do not form in them), but it hardly plays any role in the dynamics of the destruction of oocytes during their programmed destruction during the female reproductive period.

Well, in conclusion, I cannot fail to mention that the existence of menopause in so many different types refutes the trade-off hypothesis of some finite “resource” that the body can spend either on reproduction or on the maintenance of somatic cells (i.e., to extend life) . Indeed, from the point of view of individual selection, a post-reproductive individual for evolution is completely useless, so spending a valuable “resource” for the post-reproductive period of its life would be a waste of it.

Therefore, there is no resource, but there is an aging program. Rather, even a few independent programs: a program of reproductive aging, or, roughly speaking, programmed castration, and a program of slow killing of the individual itself, also divided into several subroutines (disabling the immune system, atrophy of muscles, bones, brain, impairment of hearing, vision, heart, lungs, kidneys, teeth, etc., etc.).

And yes, it seems to me that aging is a program. Like everything else in the body. Starting from the first day of embryogenesis, when a colony of trillions grows from a single cell at a breakneck speed, and ending with puberty, a regular 28-day cycle (a program!), Switching off the sexual function, etc. It would be very strange if all these processes in the body were programmed, but aging is not. After all, organisms are the most accurate programs honed by billions of years of debugging.

The key question, of course, is how can we turn off this subroutine, and where is its button. Urry, urry? It does not give an answer ... What do I personally think about this at the moment? That the central mechanism for the implementation of the aging program is epigenetics, that is, the gradual shutdown of some genes and the inclusion of others. It is clear that this process should be synchronized, which we empirically observe in the “methylation hours” of different tissues, which show very similar values at an early age and only begin to get out of sync with age.

The next logical question is whether there is a central synchronization center in the body, which sets a certain clock frequency for all cells, and whether it can be overclocked. Well, or underclock, to be exact. I see such a center in the hypothalamus, and the clock frequency in circadian rhythms. Is it possible to deceive our body by forcing its inner “day” to last not 24, but 48 or even 240 hours? Not sure, but it would be interesting to try.

And the best thing would be, of course, to learn how to centrally roll back our epigenetic clocks. That is, to tailor exactly the mechanisms that our genes launch during fertilization, giving the 30-year-old egg a permission to nullify its age and become a new individual. Of course, we cannot completely reset to zero, but learning to slowly transfer these watches to a few years ago would not hurt at all. The successful experiments of the Belmonte group from the Salk Institute on the use of Yamanaki factors for rolling back epigenetic clocks give us hope that this is possible.

In the meantime, unfortunately, modern science has no radical means of dealing with these programs of our killing and castration. But they will be. Breakthroughs in understanding epigenetics give me great hope that within 25–30 years all these harmful congenital pathologies we learn to stop and reverse. And then we can finally throw off the yoke of genes and stop being slaves of our biology.

Why are genes being so cruel to us? For the same reason that they do everything else — to maximize the integral of their reproduction over time. That is, it is important to them not the momentary maximum of the number of copies, but the area under the curve of the number of these copies in time. Like wise economists, gene cartels are not striving for explosive growth, which is fraught with collapse, but for stable, long-term sustainable growth to infinity.

Why do genes need to copy themselves? Then, why does the electron “need” to the lowest possible orbital, and the free radical to oxidize someone. So it is in our universe. And, by the way, the desire to maximize entropy, it seems, generally underlies the phenomenon of living systems (self-applicators) - at least if the calculations of Jeremy Ingland are correct.

Well, okay, let's go back two levels of abstraction above - from physics to biology. Here somehow familiar. Why do genes need mechanisms for population control? At the intuitive level, this is understandable even to a child. Indeed, it is not without reason that almost any person who first hears the proposal to stop aging immediately asks the question: “What about overpopulation?”.

Yes, overpopulation threatens genes with extinction - if their replicators eat all the nutritional resources, they will die of hunger themselves, and the team of creator genes will disappear into oblivion. And gene cooperatives that have not learned to control the population of their copiers are likely to rest for a long time in this Summer. To this day, those who have mastered this skill (aging species), or those who have learned to survive long periods of adverse conditions (plants, hydra, etc.), have survived. Although many species can do both: for example, nematodes, they can turn off aging at the larva stage if they feel a lack of nutrients in the environment.

Fortunately, thanks to the hypertrophied brain that gave us the scientific and technical progress, the rational human population is not threatened with over-extinction, but our single-celled ancestors were threatened for billions of years. I think overpopulation was the cause of the extinction of many species due to the depletion of resources of the overgrown population, until the cells invented apoptosis and telomeres, and the multicellular cells behind them did not do the same at the next level of fractality — they did not invent aging (phenoptosis) and menopause (replicative aging of the body).

By the way, the female reproductive system is the shortest-living system of our body. The term of its operation is about 35 years (from 14–15 to 50 years), with the last 10–15 years (after 35) this functioning is very mediocre. Other body systems are also guaranteed to deteriorate with age, but not so rapidly:

By the way, with the onset of menopause, other negative processes are also accelerated, for example, sarcopenia and osteopenia (loss of muscles and bone tissue):

There is an opinion that menopause is an exclusively human prerogative. Like, here we are so great, extended our lives to such an extent that we overtook our physiological limit of the reproductive system. But it is not. Menopause (or, more precisely, the post-reproductive period of life) is in many species - from flies and worms, to elephants, whales, cows , gorillas and macaques .

It is necessary to clarify that formally, a pause is the cessation of the menstrual cycles, but in its meaning is the loss of the body’s ability to reproduce. And here lies the misunderstanding of how widespread this phenomenon is in nature. Menstrual cycles are observed only in some mammals (human, chimpanzee, bat), but very many have a “post-reproductive period of life”, as I have already mentioned. Therefore, later, when I will talk about menopause, I need to understand what I mean exactly the phenomenon of age sterilization (that is, loss of reproductive function), and not the narrow meaning of this term in the sense of stopping menstruation.

And, of course, menopause, like aging, is programmed. The reproductive system does not wear out due to use, but is deliberately destroyed. That, from the point of view of population control, is absolutely logical: aging guarantees the outflow of new individuals from the population, and menopause restricts the influx.

As I have already mentioned, this method of population control is not a multicellular invention. Evolution, so loving fractality, has introduced it even from single-celled. And the telomeres that impose the Hayflick limit on the maximum number of cell divisions are, in fact, exactly the same mechanism that limits the progeny of each individual cell.

What clears this limit for single-celled and increases new telomeres? Sexual reproduction, that is, gene exchange, as a result of which a new individual is formed, receiving “permission” for the next ~ 50 divisions. Like the new female multicellular. By the way, males do not count, they generally do not participate in reproduction. Their role is only to give their partner a key in the form of a second set of chromosomes, which will open a casket with permission to reproduce the unicellular “host” of the female. This host is a sexual cell line, which was originally designed by this female to replicate its genes.

And this owner imposes very strict restrictions on reproduction for his creation. Even before the reproductive function of women finally turns off at 45–55 years old, it begins to actively deteriorate from the age of 35. Not only does the risk of egg abnormalities increase from less than 0.1% in 35 years to 3.5% in 38–40 years, and the risk of fetal trisomy (for example, Down Syndrome) increases from 5% in 38–40 years to 20% after 44 years, the mother’s risk of dying from childbirth also increases by a factor of 10 between 20 and 40 years.

Who is leading this process of active destruction of the reproductive system? The one who initially launches this system is our brain, or, more precisely, the hypothalamus with the pituitary gland.

Here are the key findings from a research on the topic:

More and more data suggests that there are several internal hours that contribute to the onset of irregular cycles, reduced fertility and the onset of menopause. We present evidence confirming that reducing the frequency and desynchronization of finely tuned nerve signals leads to poor communication between the brain and the pituitary-ovary axis, and that this combination of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian events leads to a deterioration in the regularity of cycles and the beginning of the menopausal transition. ”

In principle, the understanding that menopause does not occur due to the deterioration of the reproductive system or the depletion of ovarian stocks was among leading gerontologists back in 1950–70. Dilman, Averitt, Frolkis, Aschheim wrote about this more than half a century ago. Here is a quote from the 1977 book of my favorite “Hypothalamus, pituitary and aging” :

Aschheim, by the way, was one of those who set up a key experiment that showed that transferring young eggs to an old rat does not restore its estrous (ovulation) cycles. But if old, post-reproductive eggs are transplanted into a young rat, from which her own were previously removed, then these old eggs do not cause cessation of cycles in such rats. That is, the role of eggs in the termination of cycles is secondary:

Anyway, with eggs (oocytes) we have a strange story. 90% of them are killed before puberty: the embryo has more than 6 million, and at the time of the first menstruation there are less than 500 thousand. Although this is a thousandfold excess. Over a lifetime, no more than 500 ovulations occur in a woman. But the eggs are killed constantly, and with age, faster and faster, and exponentially:

Why does nature need to create 6 million eggs, if you use no more than 500 of them? One hypothesis is to increase the chances of genetic mutations. Yes, yes, just to increase. Because only mutations in the germ cells are inherited. And mutations are the driving force of evolution. After all, they create new variants of genes. Although women find it difficult to cope with men, who create hundreds of millions of new sperm cells every day , that is, the risk of mutations in men is 4–5 orders of magnitude higher.

There is another theory about why the female body produces so many oocytes, in order to thus minimize mitochondrial mutations in these egg cells. Presumably, when there are a lot of eggs, it will be possible to choose for each ovulation cycle in some way the one with “better mitochondria”. But this theory seems to me wrong for several reasons.

First of all, mitochondrial respiration is completely disabled in oocytes, so free radicals do not form in them, and their mitochondria do not “break down” over time, unlike other cells. Secondly, if the goal was to minimize mutations, no system would repeat the mutagenic process of creating new oocytes 6 million times, when it would be enough for it to repeat it only 500 times.

And, finally, the probability of mutation of the mitochondrial DNA during the division of each oocyte is much less than the probability of mutation in nuclear DNA: mtDNA contains only 16 thousand base pairs against 3 billion in nuclear DNA. In addition, each oocyte has as many as 100 thousand independent mitochondria, and the mtDNA mutation in one or several of the mitochondria will not affect mtDNA in all the others.

Protection of mitochondria in oocytes throughout the life of an individual could be the initial goal in separating the germ and somatic cell lines of our ancestors millions of years ago, as well as in disabling the function of mitochondrial respiration in the germ line (so that free radicals do not form in them), but it hardly plays any role in the dynamics of the destruction of oocytes during their programmed destruction during the female reproductive period.

Well, in conclusion, I cannot fail to mention that the existence of menopause in so many different types refutes the trade-off hypothesis of some finite “resource” that the body can spend either on reproduction or on the maintenance of somatic cells (i.e., to extend life) . Indeed, from the point of view of individual selection, a post-reproductive individual for evolution is completely useless, so spending a valuable “resource” for the post-reproductive period of its life would be a waste of it.

Therefore, there is no resource, but there is an aging program. Rather, even a few independent programs: a program of reproductive aging, or, roughly speaking, programmed castration, and a program of slow killing of the individual itself, also divided into several subroutines (disabling the immune system, atrophy of muscles, bones, brain, impairment of hearing, vision, heart, lungs, kidneys, teeth, etc., etc.).

And yes, it seems to me that aging is a program. Like everything else in the body. Starting from the first day of embryogenesis, when a colony of trillions grows from a single cell at a breakneck speed, and ending with puberty, a regular 28-day cycle (a program!), Switching off the sexual function, etc. It would be very strange if all these processes in the body were programmed, but aging is not. After all, organisms are the most accurate programs honed by billions of years of debugging.

The key question, of course, is how can we turn off this subroutine, and where is its button. Urry, urry? It does not give an answer ... What do I personally think about this at the moment? That the central mechanism for the implementation of the aging program is epigenetics, that is, the gradual shutdown of some genes and the inclusion of others. It is clear that this process should be synchronized, which we empirically observe in the “methylation hours” of different tissues, which show very similar values at an early age and only begin to get out of sync with age.

The next logical question is whether there is a central synchronization center in the body, which sets a certain clock frequency for all cells, and whether it can be overclocked. Well, or underclock, to be exact. I see such a center in the hypothalamus, and the clock frequency in circadian rhythms. Is it possible to deceive our body by forcing its inner “day” to last not 24, but 48 or even 240 hours? Not sure, but it would be interesting to try.

And the best thing would be, of course, to learn how to centrally roll back our epigenetic clocks. That is, to tailor exactly the mechanisms that our genes launch during fertilization, giving the 30-year-old egg a permission to nullify its age and become a new individual. Of course, we cannot completely reset to zero, but learning to slowly transfer these watches to a few years ago would not hurt at all. The successful experiments of the Belmonte group from the Salk Institute on the use of Yamanaki factors for rolling back epigenetic clocks give us hope that this is possible.

In the meantime, unfortunately, modern science has no radical means of dealing with these programs of our killing and castration. But they will be. Breakthroughs in understanding epigenetics give me great hope that within 25–30 years all these harmful congenital pathologies we learn to stop and reverse. And then we can finally throw off the yoke of genes and stop being slaves of our biology.

All Articles