Strange brain of the greatest solo-climber of the world

Alex Honnold doesn’t feel fear like we do.

Alex Honnold has his own personal verb. “Honnoldit” - standing in some high, unreliable place, with your back to the wall, looking straight into the abyss. Literally look fear in the face.

This verb appeared thanks to the photographs of Honnold, standing in that position on the ledge "Thank God" [Thank God Ledge], located 600 meters from the plateau in Yosemite National Park. Honnold made his way sideways along this narrow stone threshold, pressing his heels against the wall and touching the abyss with his toes, when in 2008 he became the first solo climber who had conquered the Solid Granite Wall of the Half Dome alone and without a rope. If he had lost his balance, he would have fallen down for 10 terrible seconds to meet his death. One. Two. Three. Four. Five. Six. Seven. Eight. Nine. Ten.

Honnold is the greatest free-climber in history. This means that he is climbing without ropes or protective gear. Any fall from a height of 15 meters or more is likely to be fatal, which means that in particularly epic days of solo ascents, he spends 12 or even more hours in the death zone. On the most difficult sections of some routes, his fingers touch the stone no more than the fingers of most people have on the smartphone screen, and the toes cling to protrusions as thick as a strip of chewing gum.

Even watching videos with Honnold's climbs can cause bouts of fear of heights, heartbeat acceleration and nausea in most people - if they can watch such videos at all. Even Honnold himself says that when watching a video with his participation his hands are sweating.

All this made Hönnold the most famous climber in the world. He appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine, on 60 Minutes, on Citibank and BMW ads, and on a bunch of viral videos. He can argue that he feels fear (he said that standing on the edge of the ledge "Thank God" is "amazingly scary), but at the same time he became a symbol of fearlessness.

Also, he has no shortage of comments from various kinds of public, claiming that he is not okay with his head. In 2014, he gave a report at the Researchers' Lounge at the headquarters of the National Geographic Society in Washington. The crowd was also interested in alpine photographer Jimmy Chin and veteran researcher Mark Sinnot, but mostly everyone came to marvel at the stories about Honnold.

From the stories of Sinnoto, the public liked the story about Oman most of all, where his team traveled by sailing boat to the remote mountains of Musandam Peninsula, acting like a skeleton hand deep into the Persian Gulf. They stumbled upon an isolated village and moored to hang out with the locals. “At some point,” says Sinnott, “these guys started screaming and pointing up at the rock. Our people began to say: "What is happening?" And I, of course, immediately thought: "Well, in my opinion, I know what it is."

The audience gasped when the photo appeared on the screen. She was wearing Honnold, the usual-looking guy who was sitting on the stage in a gray sweatshirt and khaki pants — only in the photo he looked like a toy climbing a huge bone-colored wall towering outside the city. (“The stone was not of the best quality,” Honnold will say later.) He was alone, without a rope. Sinnott summarized the reaction of the locals: “Simply put, they decided that Alex was a sorcerer.”

At the end of the presentation, adventure seekers settled for autograph distribution. Formed in three stages. In one of them was a neurobiologist, who was waiting for the opportunity to talk with Sinnot about the part of the brain that includes the feeling of fear. A worried scientist leaned closer to him, glanced at Honnold, and said: "This guy has a cerebellar amygdala not working."

Once upon a time, Honnold tells me, it would be scary for him to give psychologists and scientists the opportunity to examine his brain, probe the behavior and follow his personality. “I always preferred not to look inside the sausage,” he says. - Well, like, if it works, it works. Why ask questions? But now it seems to me that I have crossed this line. ”

And so in March 2016, he lay like a sausage inside a large white pipe at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. A tube is an apparatus for scanning the brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging , fMRI, in fact, a giant magnet that shows activity in various parts of the brain by tracking blood flow.

A few months before that, I asked Honnold to study his brain, which someone admires, and someone condemns. “I feel completely normal, whatever that means,” he said. “It would be interesting to see what science will say.”

The neuroscientist cognitive who volunteered to scan is Jane Joseph. She was one of the first to perform an fMRI-study of the brain of thrill-seekers in 2005 — they studied people who were willing to take risks in order to experience strong feelings. For decades psychologists have been studying the love of strong feelings, because it can often lead to uncontrollable behavior, such as addiction to drugs, alcohol, unsafe sex and gambling. In Honnold, Joseph spotted the possibility of studying a more interesting topology: a lover of super-acute sensations, going beyond the dangerous situation, while still being able to tightly control the reaction of mind and body. In addition, she is delighted with the possibilities of Honnold. She tried to watch videos in which Honnold scrambles without a rope, but, not belonging to the caste of lovers of strong feelings, found them too overwhelming.

“I look forward to seeing what his brain looks like,” she says, sitting in the control room behind the crystal glass before scanning. “And then we will check what the amygdala does, and find out - is it true that he does not feel fear at all?”

The amygdala is often called the “center of fear” of the brain — more precisely, it is the center of the threat response system and interpretations. He receives information directly from our senses, which allows us, for example, to move away from the abyss without any conscious effort, and also activates one of the whole list of body reactions familiar to everyone: rapid heartbeat, sweating palms, tunnel vision, loss of appetite. Then the amygdala sends information further along the chain, where it is processed by the structures of the cerebral cortex, and possibly turned into a conscious emotion, which we call fear.

The first results of an anatomical scan of Honnold's brain appear on the computer screen of James Purle, an MRI technique. "Can I go to his amygdala?" We need to know, ”says Joseph. The medical literature describes examples of people with rare congenital features, for example, Urbach's disease - Vita , because of which the amygdala is damaged and degraded. Usually such people do not experience fear, but they have other strange symptoms, such as a lack of respect for personal space. One of these people felt quite comfortable standing nose to nose with another person and looking him straight in the eyes.

Purl scrolls through the images further and further, through the Rorscharkhov topography of the Honnold brain, until with a sudden photobomb a couple of almond-shaped knots appear on the screen. “He has her!” Says Joseph, and Purle laughs. We'll have to look for another explanation of how Honnold is able to climb in the death zone without ropes - this is not due to the fact that instead of the amygdala he has an empty space. According to Joseph, at first glance, the brain looks completely healthy.

In the tube, Honnold looks at a set of about 200 rapidly changing images. Photos should scare him or lead to a state of excitement. “At least in other people they cause a vibrant response in the amygdala,” says Joseph. “I myself cannot look at some of them.” The set includes corpses with bloodied and twisted faces, a toilet with waste products, a woman shaving a bikini area, and a couple of photos with rock climbers.

“Maybe its amygdala doesn't work — and it has no internal reactions to these stimuli,” says Joseph. “But he can have such a polished regulatory system that he can simply say to himself: 'Well, I can feel it all, the amygdala works,' but at the same time its bark is so powerful that it can calm him down.”

There is a more existential question: “Why is he doing this? She says. - He knows about the threat to life - I am sure that people tell him every day about it. Perhaps there is some serious reward system, the pleasure of these experiences. "

In search of the answer to the last question, Honnold passes the second experiment, the “reward task,” in the scanner. It can win or lose small sums of money (maximum $ 22), depending on the speed of pressing the button after the signal. “We know that in ordinary people this task activates the brain circuit responsible for rewards,” says Joseph.

In this case, it closely monitors another part of the brain, the nucleus accumbens , located near the amygdala (also part of the reward circuit) at the upper edge of the brain stem. It is one of the key handlers of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with desire and pleasure. Thrill-seekers, according to Joseph, may need more stimulation compared to ordinary people to release dopamine.

After about half an hour, Honnold gets up from the scanner with a sleepy facial expression. He grew up in Sacramento, pc. California, and demonstrates an unusually open manner of communication, and a contrasting attitude to life, which can be described as overly calm. His nickname, “Nothing” [No Big Deal], describes his attitude to almost any experience he experiences. Like most experienced climbers, he has a wiry body, more reminiscent of a fit fitness enthusiast than a bodybuilder. The exception is made by his fingers, constantly looking as if they were pinched by a car door, and forearms reminiscent of such a character as the sailor Papay.

“Looking at these pictures is considered stress?” He asks Joseph.

“These pictures are quite often used in our business to excite strong responses,” says Joseph.

“Because, well, I don’t know for sure, but I, in general, didn’t care,” he says. The photographs, even the “terrible images of burning children and all that,” did not make a special impression on him. "It's like walking through a museum of curiosities."

After a month of studying images of Honnold's brain, Joseph participates in a conference call with Shanghai, where Honnold is going to climb with the help of ropes on the underbelly of the Great Getu Arch.

Uncharacteristically for Honnold, his voice betrays fatigue and even stress. A few days before in the city of Index, pcs. Washington, he passed a simple route to strengthen the ropes for his girlfriend's parents. When the girl, Sunny McCandles, lowered him to the ground, he suddenly fell from three meters and landed on a pile of stones - the rope was not enough to get to the ground, and its end slipped from the hands of the McCandles. “It was just a small joint,” he says. He received a compression fracture of two vertebrae. It was the most serious accident in all his climbing, and everything happened when he was tied to a rope.

“And what do all these brain images mean?” Asks Honnold, looking at the brightly colored fMRI images sent to him by Joseph. "Is my brain alright?"

“The brain is fine,” says Joseph. “And this is very interesting.”

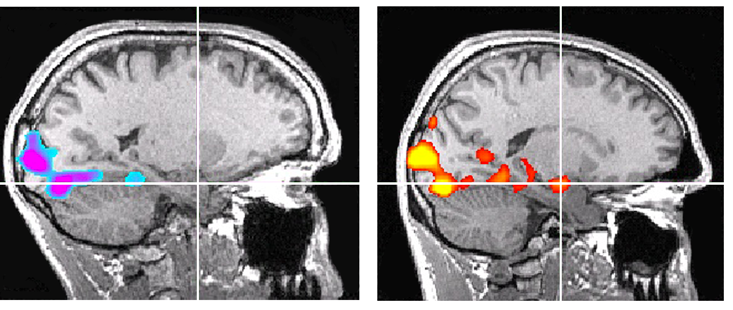

Even for an untrained eye, the cause of interest is quite obvious. Joseph used the test subject — a male, a rock climber, a thrill-seeker, about the same age as Honnold — for comparison. Like Honnold, the control test subject described the task of viewing pictures in the scanner as not particularly challenging. However, in the fMRI images of the brain response of two men, where the brain activity is marked bright purple, the amygdala of the control test resembles a neon sign. Honnold has a gray one - no activation.

On the left - Honnold's brain, on the right - the control test subject, also a climber of about the same age. At the cross is the amygdala. When looking at the set of pictures, the control test patient has the amygdala activated, while Honnold remains completely inactive.

We switch to scans made while performing the task with rewards: and again, the amygdala and several other parts of the brain of the control test subject “are lit like a Christmas tree,” says Joseph. In Honnold's brain, the only activity is in the area processing the visual information, which confirms only that he was conscious and looked at the screen. The rest of the brain is lifeless in black and white.

“In my brain, just a little is happening,” Honnold says thoughtfully. “He’s just not doing anything.”

To check that she missed nothing, Joseph is trying to reduce the statistical threshold. As a result, she finds a single voxel - the minimum amount of brain tissue that is tracked by the scanner - activated in the amygdala. But by this time the real data can no longer be distinguished from errors. “There is no visible amygdala activation anywhere within a decent threshold value,” she says.

Can the same thing happen when Honnold goes up without ropes in situations in which any other person would be dismayed? Yes, says Joseph - in principle, she believes that this is exactly what is happening. Without activation, most likely, there is no response to the threat. Honnold really has a unique brain, and he may not really feel fear. Totally. At all.

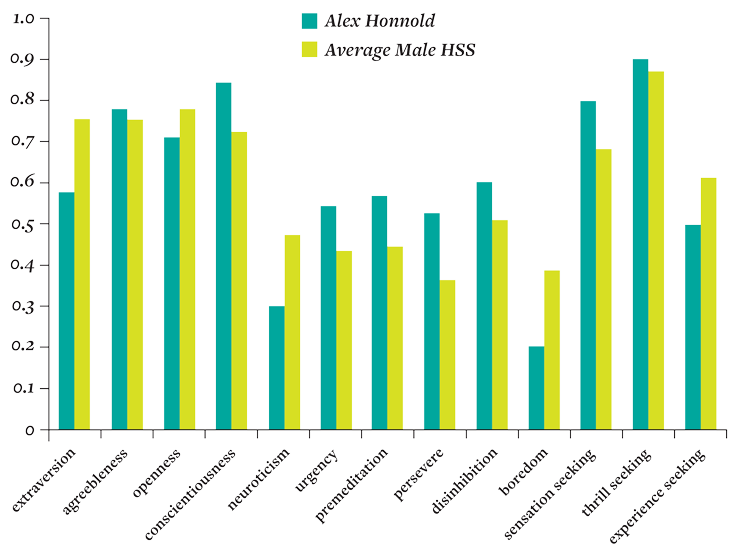

Joseph was surprised by the results of the Honnold personality research. Despite his calmness and concentration during the ascents, he is sharper and more disinhibited than the average thrill-seeker, suggesting the presence of risky impulsivity.

Research items (green is the Honnold result):

- extraversion

- willingness to agree

- openness

- consciousness

- neuroticism

- impulsivity

- prudence

- perseverance

- disinhibition

- boredom

- search for sensations

- search for thrills

- search for new experience

Honnold has always rejected the idea that he has no fear. He is known to the world as an example of unnatural tranquility, when he hangs on his fingertips from a thin line between life and death. But no one watched him when he, more than ten years ago, at the age of 19, stood at the foot of his first serious climbing route without a rope - the Wrinkled Corner, in the area of Lake Tahoe, California. On the scale of difficulty used by climbers, the Wrinkled Corner has a rating of 5.7 - almost 15 points easier than the most complex route traveled by Honnold by that time. But still, its height is 90 meters. “If you fall, you will break,” says Honnold.

To climb this solo route, he first had to have a desire to do it. “It seems to me that my uniqueness is not in the ability of a solo ascent, but in the presence of a desire to do it,” says Honnold. His heroes were rock-climbers without ropes, like Peter Croft and John Bachar , who set new standards in style in the 80s and 90s. (Honnold, among other things, was also terribly shy, which made it difficult for him to find partners for climbing with a rope.) He saw their photos in climbing magazines and immediately realized that he wanted to find himself in the same position: terribly vulnerable, potentially deadly , fully under control.

In other words, he is a classic thrill seeker. On the day he climbed into the fMRI tube, Honnold also filled out several psychological questionnaires used to measure his degree of addiction to seeking sensations. He was asked to agree or disagree with such statements as “I would like the feeling of very fast skiing from a high mountain” (“I just love skiing down the mountain,” he says); “I would love to jump with a parachute” (“I learned skydiving”); “I like to explore unusual cities or their districts on my own, even if there is a danger of getting lost” (“For me, this is everyday life”). Once he filled out a similar questionnaire at an exhibition of goods for outdoor activities, in which an illustration of the question “did he ever think of climbing” was his own photo.

However, Honnold was very frightened at the Wrinkled Corner. He clutched at large and friendly ledges. “My grip was excessive,” he says. Obviously, he did not give up after the first such experience. On the contrary, Honnold acquired what he calls "mental armor," and constantly crossed the threshold of fear. “For each of my difficult solo routes, there must be a hundred simple ones,” he says.

Gradually, his attempts, which at first seemed terrible to him, began to seem not so insane: a solo device in which he clings to the stone with only his fingers, while his legs dangle in the air; or, as he did in June on the notorious Absolute Shriek, an ascent without a rope on a slope he had never climbed before. For 12 years of solo climbing without insurance, Honnold’s hands broke off, his legs slipped off, he went from the well-known route to the unknown, he was frightened by animals such as birds and ants, or he was overtaken by “fatigue on the edge when you were too long above the abyss.” But as he dealt with these problems, he gradually pacified his anxiety about them.

From the point of view of Marie Monfils, who heads the Fear Memory Lab at the University of Texas, the Honnold process resembles an almost elementary, albeit brought to the limit, way of working with fear. Until recently, according to Monfils, psychologists believed that memories - including memories of fear - are consolidating, becoming immutable soon after the acquisition. But over the past 16 years, this view has changed. Studies have shown that every time we recall a memory, we re-consolidate it, that is, we can add new information or another interpretation of what we remember to it, and even turn fear-related memories into fearless ones.

Honnold has a detailed log of ascents, in which he constantly reviews his ascents and notes that he can be improved. He also prepares for his most difficult ascents for a long time - rehearsing movements, and then presents all movements in perfect performance. To prepare for the ascent of the 365-meter wall, he visualized everything that could go wrong, including falling from a height and bleeding from the stones below - to reconcile with these possibilities before leaving the earth. Honnold completed this ascent on a wall known as the “Moonlight Column” in Zion National Park , 13 years after the first ascents, and four years after the start of the solo ascents.

Returning to the memories in order to present them in a new light, says Monfils, is a process that almost certainly takes place in all of us in the head completely unconsciously. But deliberately returning to them (as Honnold did) is much better - “a great example of reconsolidation.”

– -, , – . « , , », – . , , , (, , ), , .

« , , , , , – . – , ».

- . . . , , , . , . , . . , . . , .

«, , , : ', ', – . – , . ' , , , , '. „“ . , ' , ' ».

2008 « », « » - . , « „ “ ».

, -, , , – . .

, - , 80-, , , – – . , «» , : « , ». , , , « ».

, , , , , «» – , . , , , , , . « , , , - , , – . – , , ».

, -. , . . , , .

( «»), « » – . , , 20% . , , , .

, . , , – , , . « , – , – ».

« , », – . , , - « », .

« – , – . , , , , – . – , , ».

, - , , . ( , ). , , – , , .

. , , , , , .

. – – .

-, : « , – , ? It's amazing. – , ».

, , ( ) , . « , », – , . « , , ».

, , , , , . , .

, , « », , -. . , , .

, , , , . . , « », , – .

: 2010-, 300- , - , . , , . , – , . , - , : « ».

, -, . , « -», .

, . , . , – , , , , , . , , .

, , , . – , – , , , . , . , , .

« - , . », – . , , 900 . , , , .

« , », – . , . , . – , . « , – , – , , ».

All Articles